Food and Nutrition for Health: Challenges of Malnutrition

Share this step

We have often heard of the phrase “food as the first medicine”. In other words, food and adequate nutrition are the foundations for so much of our health. Feeding the world’s population is a huge challenge to our society, and a major challenge to achieving SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being. Let’s look at some of the aspects of this challenge and the impact of nutrition on our health.

The enduring challenge of malnutrition

The MDGs aimed to cut hunger by half. Despite huge improvements between 2000–2015, globally one in nine people in the world (or 795 million people) are undernourished. Poor nutrition causes the deaths of approximately 3 million children under five per year. A related SDG, SDG 2, sets an even more challenging set of targets, with the aim to “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.”

How can we recognise hunger and malnutrition?

When we talk about hunger we are referring to the distress associated with lack of food. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) defines food deprivation, or undernourishment, as:

“the consumption of food that is not sufficient to provide the minimum amount of dietary energy that each individual requires to live a healthy and productive life, given his or her sex, age, stature and physical activity level.”

Dietary energy is typically measured in terms of calorie intake. The recommended daily allowance of calories varies according to an individual’s age, gender, and level of activity. Adult females require an average of 2,000 calories a day, and adult males an average of 2,500 calories. See the US Department of Agriculture’s figures for a more detailed breakdown.

Malnutrition refers to both undernutrition and overnutrition which are both problematic.

Undernutrition and overnutrition

When we talk about the term undernutrition, this goes beyond calorie intake. Undernutrition means being deficient in energy, protein, or essential vitamins and minerals. It is the result of inadequate intake of food in terms of either quantity or quality, poor utilisation of nutrients due to infections or other illnesses, or a combination of these factors. Undernutrition is the underlying contributing factor in about 45% of all child deaths, making children more vulnerable to severe diseases. Malnourished children, particularly those with severe acute malnutrition, have a higher risk of death from common childhood illness such as diarrhoea, pneumonia, and malaria.

We have considered undernutrition but what about overnutrition?

Undernutrition refers to deficiencies whereas overnutrition refers to problems with unbalanced diets, which include consuming too many calories in relation to energy requirements. In recent years, for the first time the world has more people who are obese than malnourished. A recent study in The Lancet, of trends across 200 countries, found that over four decades, up to 2014, the global prevalence of underweight men decreased to 8.8% and women to 9.7% compared with the global prevalence of overweight men which increased to 10.8% and women to 14.9%.

Overnutrition and obesity are associated with many of the non-communicable diseases that are starting to put a large burden on our health systems today such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Later on this week, Ross will be exploring this in more detail.

Undernutrition and overnutrition can occur in the same country or region; they are not mutually exclusive. The worldwide number of overweight children increased from an estimated 31 million in 2000 to 42 million in 2015, including in countries with a high prevalence of childhood undernutrition.

Challenges facing world malnutrition

The major challenges that countries face to reduce malnutrition are varied and complex. For example, these are some of the challenges that impact the ability of individuals and households to achieve adequate nutrition:

- Inadequate maternal or child health practices

- Inadequate access to health services

- Inadequate food supply chains in countries or regions

- Climate change

- Food insecurity

Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

The four main dimensions of food security are:

- Availability

- Access

- Utilisation

- Stability

Food security at a global level is monitored by organisations such as the Famine Early Warning Systems Network. We will examine the case of food insecurity in Uganda and its consequences later this week.

So given the importance of food as medicine, how best can we measure how the world is facing this challenge?

The Global Hunger Index

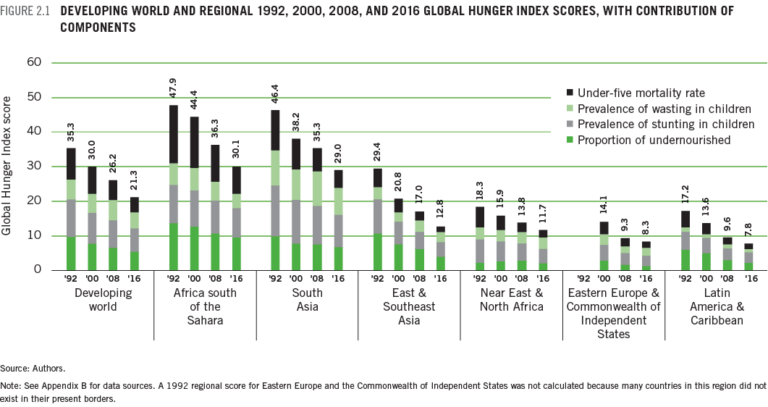

This is a map of the world that describes the Global Hunger Index (GHI). It highlights countries that face the challenge of hunger. GHI is a tool designed to measure and track hunger globally, regionally, and by country.

The Global Hunger Index. Click here to enlarge

The Global Hunger Index. Click here to enlarge

Each year, the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) calculates GHI scores in order to assess progress, or the lack thereof, in decreasing hunger. An increase in a country’s GHI score indicates that the hunger situation is worsening, while a decrease in the score indicates an improvement in the hunger situation. A country’s GHI score is made up of 4 components:

- The proportion of the population that is undernourished

- Child stunting per population

- Child wasting per population

- Child mortality per population

Since 1992 the GHI shows a drop across all four components in all regions of the world indicating improvement.

These improvements reflect the fact that there has been major progress since 2000 in the fight against hunger.

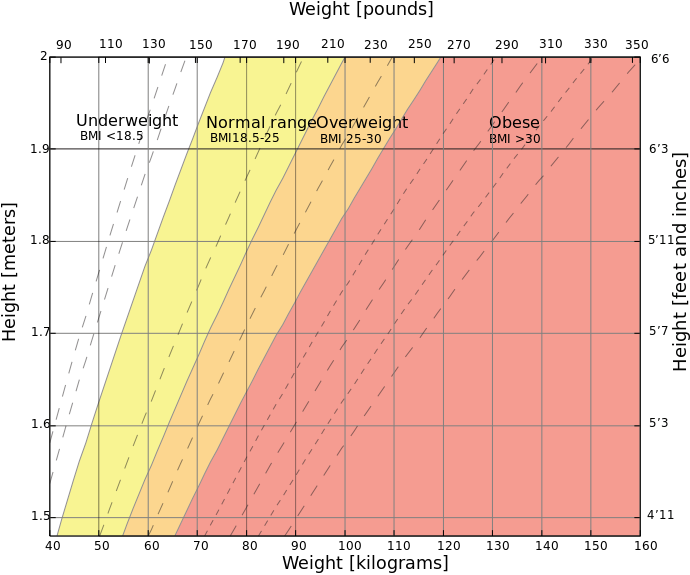

Measuring nutritional status with the Body Mass Index

Another way that health and nutritional status is often measured is using the Body Mass index (BMI). To get an individual’s BMI we measure their height and weight, and then divide their weight in kilograms by their height squared in centimetres. We then use a BMI table to determine whether a person is within a normal range for their age, or whether they may be underweight or overweight. A BMI of 18.5–25 is within the normal range. Under 18.5 is underweight, with 17–18 being mildly malnourished, 16–17 being moderately malnourished, and under 16 severely malnourished. What about the other end of the spectrum? A BMI of 25–30 is overweight and above 30 is obese.

Body Mass Index Chart

Body Mass Index Chart

BMI is a common and useful measure but it is a rough measure. Nutritionists increasingly recommend using a collection of measures in order to understand nutritional status, to be able to determine the right course of treatment for under and overnutrition, and the right timing of that treatment.

Measuring nutritional status with ABCD

A comprehensive measurement of nutritional status will take into account multiple measures including some, or all, of the ABCD of measures.

- A is for anthropometry; this refers to the measurement of body parameters to determine nutritional status. BMI is a common anthropometric measure.

- B is for biochemical tests; this is where we take blood or urine samples and use them to assess whether a person has adequate micronutrients.

- C is for clinical history; this is where we assess a patient’s clinical profile including symptoms and history of illness.

- D is for diet; this is where we assess a patient’s actual food intake, often using tools like 24 hour dietary recall or food frequency questionnaires.

Nutrition researchers will seek to get as many measures as possible to fully understand a person’s nutritional status and assess their health.

Take a look at the Global Hunger Index score from 2017 and choose one country.

- What challenges do you think that country faces to reduce malnutrition?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free