Infrastructure: connecting people and connecting places

Share this step

Cities that work need to be successful in managing a number of core tasks from organizing sewerage, water and sanitation, garbage collection, electricity, public safety, as well as ensuring urban mobility.

One of the targets of SDG 11 is directly related to urban mobility: “By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons”. In this article we will focus on urban mobility, and start with asking: why is it so important?

Urban mobility refers to the movement of an urban resident from location A to location B. This movement will typically be characterized by a mode of transport, duration and cost. For example, it takes 40 mins to walk from Times Square to Washington Square Park in New York City; alternatively, one can hop on the subway at a cost of US$ 2.75 which will take roughly under 20 mins. A taxi will take between 12-30 mins, depending on traffic.

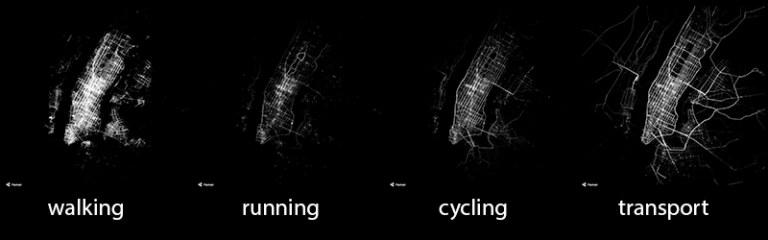

Urban data visualizations of New York City. Copyright Margarida Fonseca, Flowing City.

Urban data visualizations of New York City. Copyright Margarida Fonseca, Flowing City.

Why is urban mobility important?

The literature that has studied cities in the United States and Europe shows that when people gather, they benefit from various – what we call – agglomeration economies. Agglomeration economies are the forces that lead firms to locate close to each other.

These can be divided into three rough categories: matching, sharing and learning.

-

A larger population size allows a better match between workers and firms, so that firms find the perfect worker for themselves and workers find their perfect employer. When people live at higher densities, workers can choose from more firms, and firms can choose from a larger pool of workers.

-

Sharing refers to the ability of firms sharing certain inputs. For example, a firm exporting to Europe might want to seek legal advice on what paperwork needs to be submitted, and what the customs formalities are. If there is only one firm exporting a product, it is not profitable for a legal firm to open an office in a location. However, if there is a cluster of firms requiring these services, it becomes profitable for a firm to open an office.

-

Third, benefits from agglomeration through learning are about people exchanging ideas when they are close to each other. For example, employees from one company go for lunch with employees from another.

From all of these above examples you can see that in order for people to get to the job they have a good match with, in order to mingle with employers from different sectors, and in order to easily meet with firms that offer services, they need to be able to move from one location to another. Despite the improvements in communication technologies, face-to-face interactions remain hugely important.

This means that if we cannot move around easily, we lose some of the very benefits that make cities the most productive and innovative places in the world: the ability to connect individuals.

Urban connectivity is often much worse in cities in low-income countries. For example, in 2013, residents of Nairobi could access only about 6% of jobs within 45 minutes using a Matatu, compared to 20% of jobs that can be reached by London residents within 45 minutes using public transit (Lall, Henderson and Venables, 2017).

In addition to limiting the benefits of density, costly urban mobility also limits urban residents’ access to key amenities and services, such as health and education or access to green spaces.

One of the challenges to urban mobility and connectivity is urban congestion.

What do we know about solutions to urban congestion?

Congestion is common in many cities across the world. A common response to urban congestion might be to build more roads to accommodate more cars. In many cities in which core urban roads are still unpaved, construction of roads is crucial.

Unpaved roads in Senegal

Unpaved roads in Senegal

However, this does not mean that more roads will necessarily solve all congestion problems. Research by Duranton and Turner (2011) in the United States has shown that the demand for driving will increase almost exactly one-for-one as the number of roads increases. As Ed Glaeser has put it: ‘You build it and they drive it’. There are also significant distributional concerns when tax payers’ money is used to finance roads. In the absence of taxes on cars, fuel, or tolls on roads, it is effectively a transfer to car owners.

There are several successful strategies to deal with urban congestion that have been implemented in various parts of the world. Pioneered in Singapore is a congestion charge imposed on drivers who want to enter central locations in a city. This reduced congestion and increased air quality. Similar policies have been introduced in London, Milan and Stockholm.

While congestion charges are agreed to be an efficient policy response to urban congestion, political economy arguments often render them difficult to implement when political clout rests among the wealthy who benefit most from accessing a city by car. Furthermore, these policies might be unpopular in the short run, until people realize their positive effects. If election cycles are short, political leaders implementing a congestion charge could risk their chance of re-election, a price they might not be willing to pay.

Hand-in-hand with reducing the number of cars to reduce congestion goes investing into other forms of urban mobility. These include:

- Bike share schemes

- Bus rapid transit schemes

- Regular buses and subways

- Widened sidewalks

How do we know which mode of transport is most appropriate to connect a given set of locations? Unfortunately, there is no easy answer to this. The most suitable investment strongly depends on the case: how many people will avail of the service, what are alternative modes of transport, alternative uses of resources, or what are possible unintended consequences? Engaging in rigorous cost-benefit analyses is essential.

- Think about when you were stuck in traffic last – what was the reason for it?

- What options do you have to commute to work and why do you choose your current way of commuting?

- What could the government do to improve your commute?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free