The Future of Healthcare: Precision Medicine

Share this step

Note: There are some graphic images in this article which some learners may find disturbing.

In the future, we hope to use scientific advances to develop new, more targeted treatments to tackle disease. One of the most exciting developments of the last century has been the mapping of the human genome. Let’s look at how this new knowledge may be harnessed to improve treatment of disease types that are becoming increasingly problematic.

Many of the most common diseases worldwide are affected by factors both in the environment and in our own genetic make up. How we respond to environmental “exposures” is very often determined by our genes. Diseases which are caused by environmental factors conspiring with our genes are called complex diseases. This is because they depend on many factors, both genetic and environmental, that work together to cause the disease.

The rise of non-communicable diseases

There is currently a plague of overweight and obesity that is currently sweeping the globe. With that comes many non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension, heart disease and stroke, diabetes, chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), and a variety of cancers. Examples of environmental exposures in this case would be factors like excessive food intake, the quality of nutrition, and associated lifestyle changes such as reduced physical activity and tobacco use. According to the WHO, the health burden imposed by NCDs is growing rapidly and becoming the dominant cause of death in the developing world.

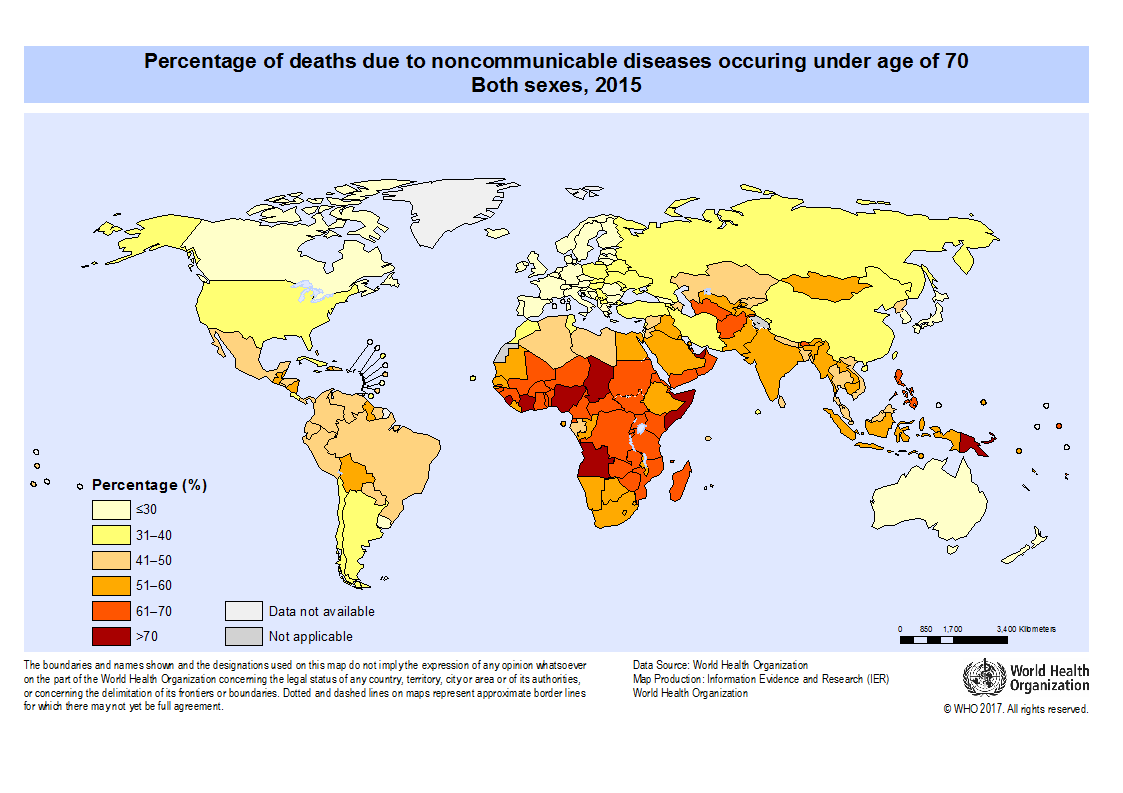

Percentage of deaths due to non-communicable diseases occurring under the age of 70 for both sexes. © United Nations. Click here to enlarge

Percentage of deaths due to non-communicable diseases occurring under the age of 70 for both sexes. © United Nations. Click here to enlarge

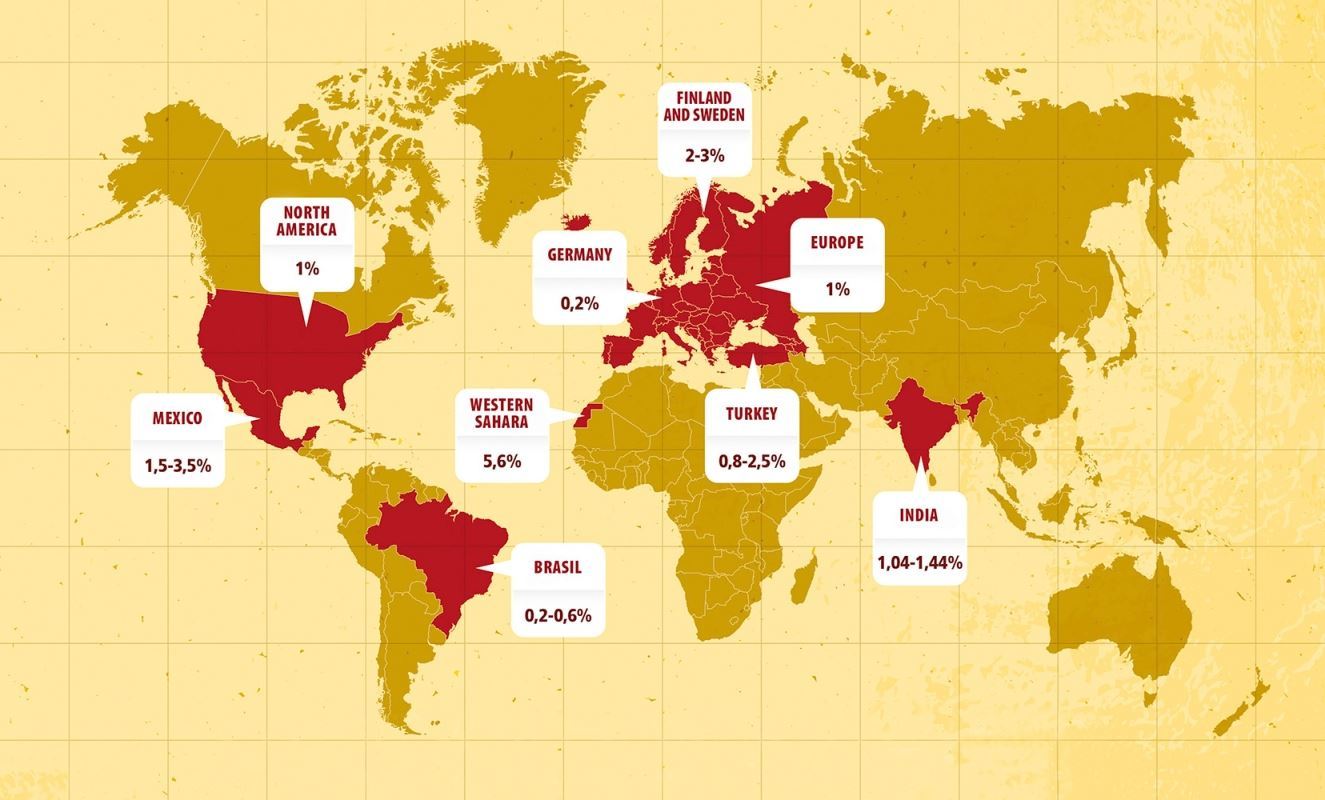

Many other NCDs are also important in the West and increasingly in resource-poor countries, including various forms of disease relating to our immune systems. These include forms of arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, and coeliac disease. Coeliac disease is caused by eating cereal proteins, and has its highest prevalence among certain populations in North Africa.

Sketch of a new epidemiology of coeliac disease, characterised by growth in the traditional fields and spread into new regions of the world. © Prof Carlo Catassi Click to enlarge

Sketch of a new epidemiology of coeliac disease, characterised by growth in the traditional fields and spread into new regions of the world. © Prof Carlo Catassi Click to enlarge

Managing or combating these diseases can be greatly aided by identifying both the environmental and genetic factors which together predispose to disease. While we can identify environmental factors, avoiding them can be very difficult – take the relentless march of obesity, lung disease, and cancer. Avoiding wheat is not easy either, especially if the alternatives are not palatable or even available.

However, there is a new and exciting way of managing disease by looking at genetic factors through an approach called precision medicine.

Precision medicine for combating disease

Knowing about our genetic make up allows us to identify groups of patients who can benefit from targeted therapeutics – an approach called precision or personalised medicine.

For example:

- We know that breast cancer treatment with the drugs tamoxifen and herceptin only works if the patient has had a particular genetic change or mutation. Other breast cancer patients see no benefit from taking these drugs.

- Treatments such as the anti-clotting agent warfarin are highly dependent on what genetic variants the patient has. The same dose could be ideal for one patient, but cause dangerous bleeding in the next. Differences between individuals in the rate at which drugs are broken down or excreted can be genetically determined and enormous. This can have big implications for all sorts of diseases including HIV/AIDS.

This is at its early stages in developed nations but will also be important in resource restricted settings. If we can understand the genetic underpinnings of diseases, we can predict who is at greater risk of developing a disease. For example, if a person has the genetic risk factors for a disease, they should avoid environmental exposures.

Concrete, actionable information makes people more likely to comply with health advice which may be difficult or burdensome – as compared with some vague warning about increased risk.

The economic value of precision medicine

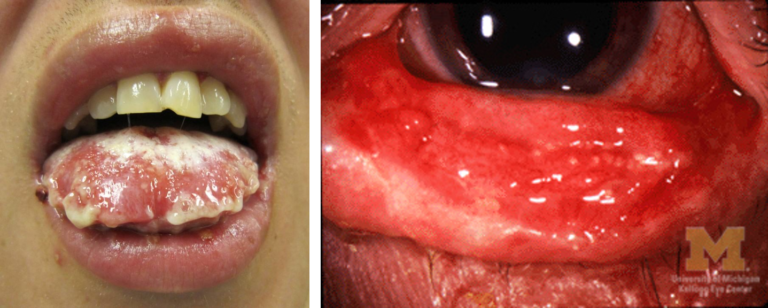

In Asia, precision medicine is being used to identify individuals at high risk of developing Stevens Johnson Syndrome/ Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (SJS/TEN). SJS/TEN is a very nasty, indeed life threatening, skin reaction to a wide variety of drugs including antibiotics and treatments for epilepsy. It is much more likely to develop in Asians carrying a gene variant called HLA-B*1502.

SJS/TEN symptoms © James Heilman, MD © Jonathan Trobe, M.D

SJS/TEN symptoms © James Heilman, MD © Jonathan Trobe, M.D

The economic and medical value of avoiding such a reaction is so great that Thai authorities are considering providing a “pharmacogenetics card” to carriers of this gene, to prevent their accidentally being prescribed inappropriate drugs. Taiwan has had a programme to identify carriers since 2010.

Lack of genetic information in the developing world

Precision medicine is attracting much attention due to its ability to more efficiently use scarce resources and provide much better outcomes for patients and perhaps even identify better treatments. However, precision medicine requires precision genetic information which is lacking in many parts of the world, particularly in the developing world.

China has the skills and the economic muscle to tackle this in a big way, but knowledge of African genetics is deficient, a problem compounded by the fact that these are the most genetically diverse populations on earth.

Fortunately, a number of initiatives are underway to tackle this problem with funding from the Wellcome Trust, National Institutes of Health, the EU, and the Gates Foundation in recent years (e.g. H3Africa). These projects are beginning to bear fruit with specific African genetic risk factors for obesity and diabetes recently reported.

So, these are steps in the right direction; however, other problems such as healthcare infrastructure and the availability of trained practitioners to make use of this emerging data are likely to be major obstacles. Investment in genomics of developing countries represents a deep resource of genetic knowledge relevant to human health which is likely to be beneficial to all humankind – and we need to promote it.

If we can share new knowledge and harness its benefits at a global level, we will move towards making healthcare more targeted, cost-effective, and ultimately more sustainable.

Thinking about precision medicine:

- Imagine you had a predisposition to genetic risk factors for a disease (e.g. breast cancer).

- Would you want to know?

- If yes, do you think you would be more likely to avoid environmental factors for that disease if you knew about your predisposition?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free