Delayed prescribing and de-escalating treatment

In previous steps we have looked at challenges in antimicrobial prescribing, particularly the overuse of antibiotics when they probably weren’t necessary. This step will look at how we can delay prescriptions until we are certain they are necessary so that we do not misuse antibiotics. It also looks at the need to be flexible with our prescribing and adapt treatment where necessary.

In this article, Dr Tim Nuttall, Head of Dermatology at the University of Edinburgh, will discuss opportunities for delayed antimicrobial prescribing. He also talks about the importance of de-escalation considering culture and sensitivity results.

Drivers for antimicrobial use:

The fact that there are many drivers for antibiotic use is a potential challenge. K Currie et al (who belongs to a group led by Paul Flowers at Glasgow Caledonian University) conducted a study and some of the drivers he found are listed below:

-

Trust – pet owners have a high degree of trust in their vet. They are motivated to do what the vet asks of them and trust their advice.

-

AMR knowledge – this was limited which was surprising given the education in the medical field, but this had not been passed on to companion pet owners. The most significant issue was the profound belief that the animal becomes non-responsive to antibiotics rather than the infection becoming resistant.

-

Client demand for antimicrobials – this was a genuine demand driven by a concern for pets (as they are considered a member of the family who deserves a similar standard of care to humans). Owners felt responsibility to their pet and didn’t want to compromise their care, so requested antimicrobials ‘just in case’.

-

Limited consult time and communication difficulties – this leads to the vet being more inclined to prescribe antimicrobials ‘just in case’. They don’t want to be responsible if an infection has been missed and antimicrobials weren’t prescribed.

-

Practice culture – in particular, younger vets tended to go how the practice normally did it rather than being a champion for change.

The use of AST and bacterial culture:

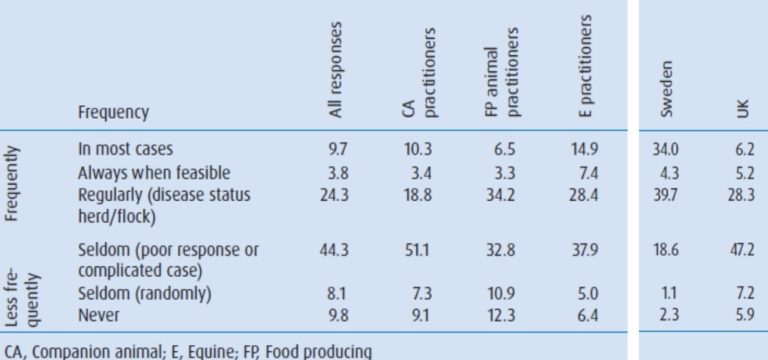

Above is some data published in the “Veterinary Record” in November 2013 (but really things haven’t shifted much since this time). The full article can be found in the downloads section below. It covered many countries in Europe, and two have been abstracted for you (Sweden and the UK).

In Sweden, nearly 80% of vets used antibiotic sensitivity testing (AST) amongst their patients, compared to a much lower percentage in vets from the UK. A lot of this was based around the disease status of production animals; so, for companion animals, cultures were only being done in the harder cases, or when a treatment failure was experienced.

The frequent use of AST in Sweden has led to an overall decrease in the use of systemic antimicrobials (especially 2nd and 3rd generation drugs like Fluroquinolones), so it is definitely something the UK should be looking to adopt. It was also achieved without compromising animal welfare or patient outcomes.

Delayed prescriptions:

After taking a culture, the next question should be, do we have to start treatment straight away or can we delay a prescription? This will require education amongst the vet profession and animal owning public (certainly in the UK), who currently have the idea of immediate therapy. However, for mild, non-life threatening, focal, surface or superficial infections you should first manage the primary disease with analgesia and the use of topical antiseptics.

The image above shows a non-healing wound on the ventral abdomen of a cat, following a surgical intervention. The temptation is to treat it straight away but as it’s nicely granulating, there is no evidence of spreading infection, the cat is otherwise well in itself and it’s not pyrexic, it was just treated with topical antiseptics until the results were back. Then, a more informed decision on treatment plans could be made, so that the clinical outcome was not compromised.

Here you can see a dog who presented with an acute flare-up of atopic dermatitis and a typical staphylococcal infection with epidermal collarettes forming. It is a very superficial infection – only in the outer layers of the epidermis and stratum corneum. It will not compromise the clinical outcomes to wait until culture results return and should be treated with topical antiseptics or an anti-inflammatory to get the dermatitis under control.

Above, you can see the axilla of a cat where there is a serious infection. The key point here is that it had developed very slowly (over a period of 9 months), so a few more days delay in treatment will make very little difference to the clinical outcome. Topical cleansers and analgesics should be used while we are waiting on the culture result. It turned out to be an actinomyces infection. Anything used empirically at standard doses would not have had an effect so it would have been an inappropriate treatment.

This dog (shown above) presented with acute cellulitis following orthopaedic surgery on his elbow. He’s pyrexic, dull and lethargic and in a large amount of pain. It’s a Friday evening and so the microbiology results will not be back until Monday at the earliest. In this situation, the clinical outcome will be compromised without treatment of antimicrobials. Cytology from these lesions was consistent with staphylococcal infection. Therefore, a post-operative staphylococcal cellulitis developing into staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome was suspected so treatment could be started.

De-escalation of antimicrobial treatment:

If we are immediately prescribing antibiotics, we tend to be governed by a ‘just in case’ idea. This can lead to escalation: a broad-spectrum antibiotic could be used in case the bacteria is both Gram-positive and Gram-negative, or in case there’s resistance, we might move up to 2nd or 3rd tier drugs, or a combinations of drugs.

It’s important to review antimicrobial therapy once we receive results:

-

If infection is more resistant than anticipated we should escalate treatment to something more appropriate.

-

If we’ve overestimated treatment (which happens more often) we can change treatment to lower tier/ narrow spectrum drug where we can: de-escalate.

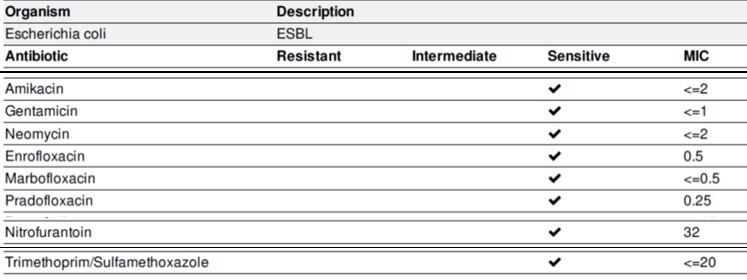

Shown above is an E. coli isolate that produces ESBL (extended spectrum beta lactamase). It can confer AMR to a wide range of drugs (especially penicillin and cephalosporins). The sensitivities shown tend us towards the use of aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones. But we can see that the E. coli isolate is also susceptible to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, so even if we start with a higher tier drug, we could de-escalate to this once the infection is confirmed.

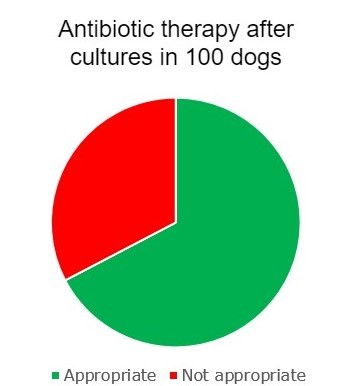

Above, you can see the results from an investigation a student did where the antimicrobial therapy before and after the culture results were obtained for 100 dogs at Dr Tim Nuttall’s hospital were investigated. In two thirds of dogs, treatment was appropriately de-escalated; in a third, it was not.

Drivers for this were vets looking at the drug they selected and seeing the infection was sensitive to it, so continuing with treatment rather than looking at the whole susceptibility to find a lower tier drug. Also, giving out a complete course of antibiotics at first visit with the owner before results were obtained; treatment couldn’t be changed without extra cost for the owner. The main messages for this are: don’t give out more antibiotics than required and wherever possible, de-escalate to a lower tier antibiotic.

In the downloads section below, please access the article by Dr Tim Nuttall that explains the use of bacterial culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and how to interpret results from these tests.

Use the comments section to discuss the use of delayed prescribing in your practice. Do you use it often or would it be a new concept to you and your colleagues? Also, how often would you say your antimicrobial therapies are de-escalated after test results come back?

In the next step we will look at times when antibiotics may not be used at all. It is really important to understand the underlying reasons for recurrent infections, as you will soon find out.

Share this

Antimicrobial Stewardship in Veterinary Practice

Antimicrobial Stewardship in Veterinary Practice

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free