Detecting Art Forgeries: What Scientific Methods Can We Use?

Share this step

A word of caution: although these scientific methods can prove a work of art is a fake, they cannot prove that a work of art is authentic. Even if the results of all scientific tests indicate that there is no deception in the artwork, we can’t say without a shadow of a doubt that this isn’t just a case of a forger out-pacing scientific detection.

The information in this article is based on the book The Scientist and the Forger by Professor Jehane Ragai.

Method 1: provenance research

The Research Archives of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Photo by Foy Scalf via Flickr

In all cases of suspected forgery, provenance research should be the first form of fake detection employed. Provenance is an art world term for an artwork’s ownership history: the record of who owned it and when. In a perfect world, we would have detailed information about who bought and sold the artwork going all the way back to the moment the original artist took it off their easel. In the real world, we are often not so lucky. Records are lost or were never kept, deals are sealed with a handshake, and, as we will discuss further in Week 3, art can be seized illegally by organisations and states who then seek to obscure the origins of the works.

Provenance investigators, then, unravel the history of an artwork using public and private records, archives, and other art historical research methods. At times, through looking at correspondence, catalogues, sales receipts, and even the artwork itself they discover it was very unlikely or even impossible for an artist to create a particular work. At other times, they might uncover a previously unknown legitimate record of the artwork’s existence which provides strong evidence that it is real.

Provenance research is relatively cheap, very effective, and can also uncover other important details about an artwork’s past, such as if it has been stolen.

Method 2: microscopy

Layers of oil paint under a microscope. Photo by the National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo

The magnifying glass has been the indispensable tool of centuries of art investigators. Modern microscopy, a broad term that refers to magnifying images, takes the magnifying glass to a whole new level. By simply looking at a small paint sample from a painting under an optical microscope, one can learn a lot about the painting. Through an optical microscope, particularly a stereo microscope which allows for 3D visuals, the investigator can get a detailed look at how paint has been layered on an artwork and, especially, can see whether paint has been added at a much later date: for example, to add Rembrandt’s signature to an old painting that isn’t actually a Rembrandt.

Famous craquelure. The small rectangular cracks on the Mona Lisa are the correct shape for Italian paintings from the period.

Microscopes are also good for observing craquelure, the cracks that appear in older paintings over time. Craquelure is like an old painting’s finger print: different paintings, from different countries, produced at different times have different craquelure patterns and they are incredibly difficult to replicate in a fake. Thus, under a microscope, art scientists can determine if a painting has the correct pattern of craquelure. If the tell-tale cracks are either missing or incorrect, the scientist knows they have a forgery on their hands.

Method 3: mass spectrometry

The Art Conservation Science Lab at the Indiana Museum of Art. Photo by Richard McCoy via Wikimedia Commons

To put it as simply as possible, mass spectrometry is used to identify exactly what pigments were used to create a particular painting. To do this, the mass of molecules in a pigment sample is determined by measuring their mass-to-charge ratio. The results are displayed in the form of a chart known as a spectrum, and the art scientist can then compare the masses present in the pigment sample to the known masses of particular elements or molecules.

For example, using mass spectrometry, the scientist can determine whether lead is present in what is thought to be a very old painting. Lead was commonly used by painters in the past, but because of the risk of lead poisoning, it is now rare and difficult to come by. No lead in the old painting raises clear questions about authenticity. Likewise, mass spectrometry can detect the presence of pigments that were not yet created when the artwork being tested was supposedly made. If mass spectrometry shows that a supposed Leonardo painting contains pigment that wasn’t manufactured until 1975, it’s pretty clear that the piece is a fake.

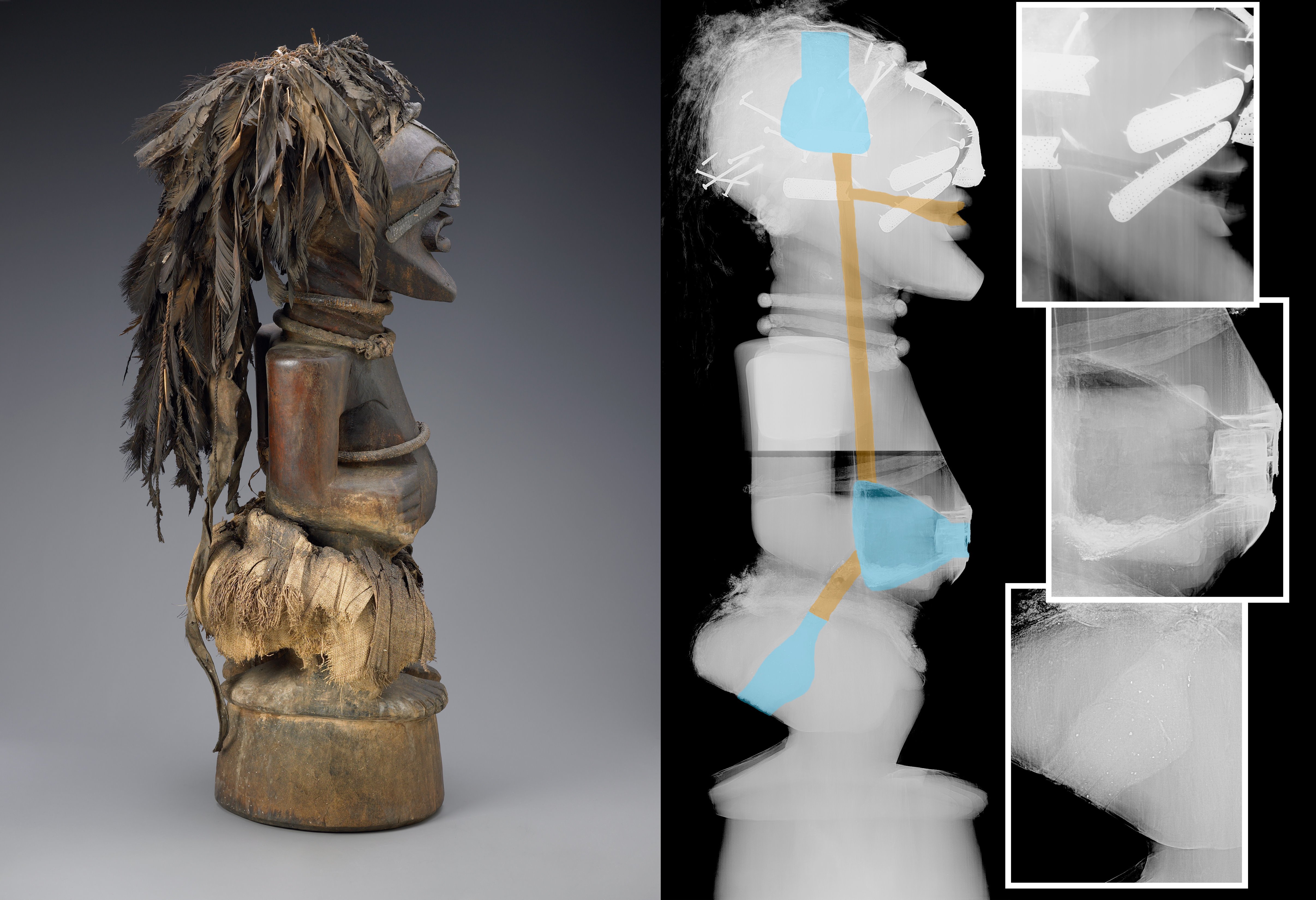

Method 4: x-ray

An art scientist employs an X-ray technique to study a painting. Photo by Richard McCoy via Wikimedia Commons

X-ray technology can also be used to determine whether a possible forgery is painted on a re-used canvas. Clever art forgers know that you can’t paint what is meant to be an old painting on a new canvas. Simply looking closely at it with, say, a microscope (see Method 2) will reveal its lack of age. Thus forgers tend to paint over less valuable but still old artworks to create a more valuable fake.

The reuse of canvasses is not unknown in the art world: starving artists from all periods sought to save money by painting over their own or other people’s paintings. But in that case, the older painting will obviously always be under the newer painting. If, for example, a suspect 17th century painting is X-rayed and what is obviously a 19th century painting is found beneath it, an art scientist would call the painting a fake. Furthermore, if through art historical research it was known that an artist only painted on new canvasses, the presence of any previous painting below the surface would be a strong signal that a forger was at work.

Method 5: infrared reflectography

Infrared light can penetrate layers of paint that visible light cannot. Graphic by Flappiefh via Wikimedia Commons

Many artists don’t just paint a whole painting directly on a canvas with no plan whatsoever. It is common practice for an artist to make at least some marks, known as underdrawings, before and during the painting process to help guide the form and structure of the piece. Some artists use pencils, others use paint. Some artists use only tiny marks, others sketch nearly complete versions of the final piece. In nearly all instances, artists use the same painting preparation technique over again and in their own distinct way. Through the use of infrared reflectography, art scientists can see below the surface of a painting and investigate the otherwise-invisible sketches below.

This technique is based on the fact that unlike light in our visual range, infrared light can penetrate the layers of pigment until it reaches an artwork’s underdrawings. The infrared light is then reflected back into a specially-designed camera which then produces an image of what is down there. If what lurks below the surface of a painting deviates significantly from an artist’s known prep method, investigators can conclude that the artwork is likely a fake.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free