This article is from the free online

Archaeology and the Battle of Dunbar 1650: From the Scottish Battlefield to the New World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

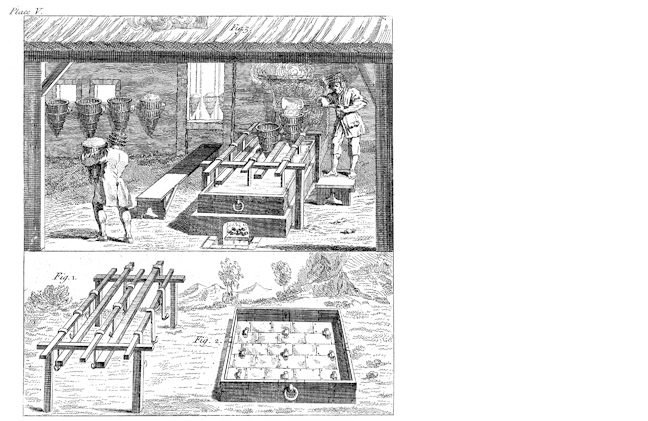

Salt-making as illustrated by William Brownrigg in his ‘The art of making common salt’, Plate V, published in 1748. The upper illustration shows the panhouse. Most of the brine has already been collected from the shallow iron pan above the furnace and the baskets of salt are now being left to drain above the pan before this new strengthened brine is crystallised. The basket support bench and iron pan are detailed below. Public domain, Internet Archive.

Salt-making as illustrated by William Brownrigg in his ‘The art of making common salt’, Plate V, published in 1748. The upper illustration shows the panhouse. Most of the brine has already been collected from the shallow iron pan above the furnace and the baskets of salt are now being left to drain above the pan before this new strengthened brine is crystallised. The basket support bench and iron pan are detailed below. Public domain, Internet Archive.