Home / History / Archaeology / Archaeology and the Battle of Dunbar 1650: From the Scottish Battlefield to the New World / Allies to enemies: Why were the Scots and English at war?

This article is from the free online

Archaeology and the Battle of Dunbar 1650: From the Scottish Battlefield to the New World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

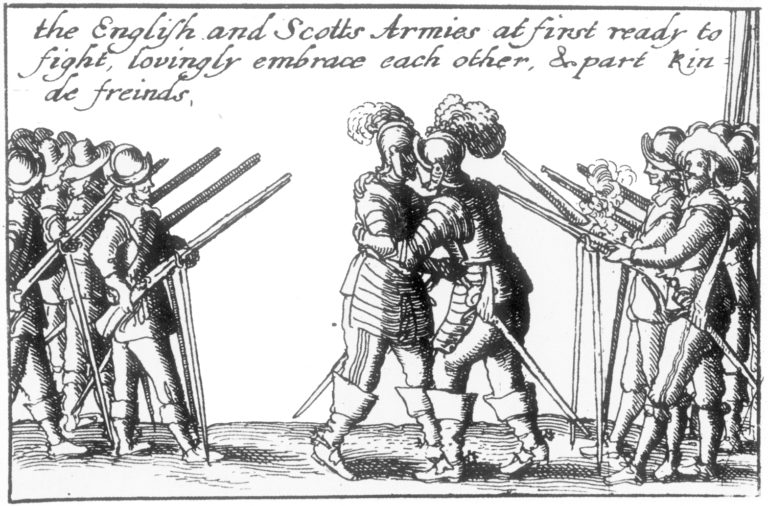

‘The English and Scotts Armies at first ready to fight, lovingly embrace each other, & part kinde freinds’. In this contemporary satirical woodcut, the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643 brings two old enemies together; laying aside centuries of conflict and mistrust, the Scots make common cause with the ‘old enemy’ England against Charles I. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

‘The English and Scotts Armies at first ready to fight, lovingly embrace each other, & part kinde freinds’. In this contemporary satirical woodcut, the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643 brings two old enemies together; laying aside centuries of conflict and mistrust, the Scots make common cause with the ‘old enemy’ England against Charles I. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.