Stages of Diabetic Retinopathy: The ICO Classification

Share this step

The original diabetic retinopathy (DR) classification system, the Airlie House classification, was developed in 1968. A modified version of this system was adopted by the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (EDTRS) in the late 1970s and this has remained the ‘gold standard’ classification for many years. However, the EDTRS system is complex which limits its usefulness for daily clinical practice and patient care.

Alternate classifications have been developed in the UK by the National Screening Council, the Scottish Diabetic Retinopathy Grading Scheme and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. These systems all recognise the two basic mechanisms that lead to loss of vision: retinopathy (the risk of new blood vessels) and maculopathy (the risk of damage to the central area of the fovea).

ICO classification

In this course we use International Council of Ophthalmology’s classification of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular oedema disease severity scales. This classification links each level (stage) of severity with clinical management.

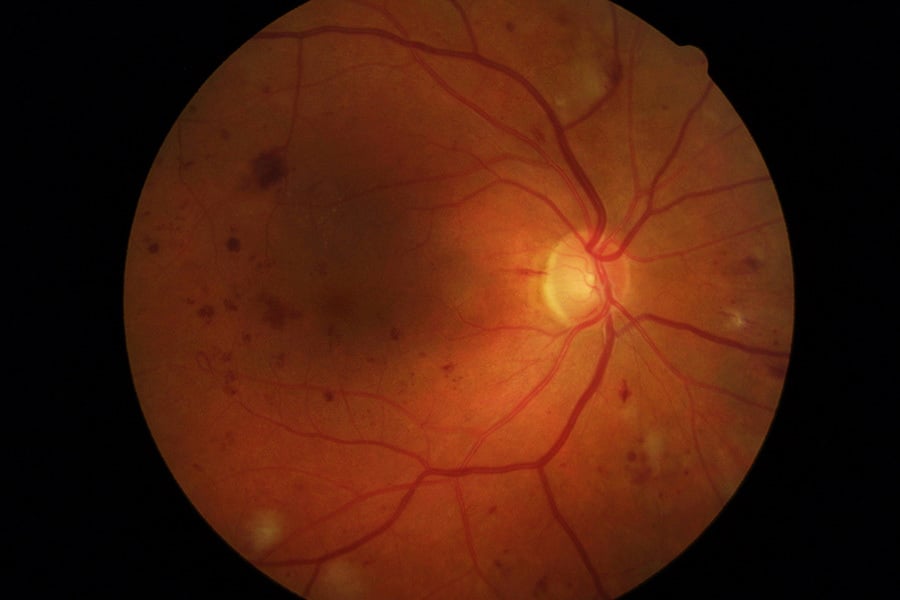

The ICO system combines evidence on disease progression as found by the EDTRS with severity of disease based on the observation of various kinds lesions in the retina:

- Microaneurysms

- Haemorrhages

- Venous beading (venous caliber changes consisting of alternating areas of venous dilation and constriction)

- Intraretinal microvascular abnormalities

- Hard exudates (lipid deposits)

- Cotton-wool spots (ischemic retina leading to accumulations of axoplasmic debris within adjacent bundles of ganglion cell axons)

- Retinal neovascularisation.

These observations are used to classify eyes as having one of two phases of diabetic retinopathy, non proliferative diabetic retinopathy or proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Eyes with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) have not yet developed neovascularisation, but may have any of the other classic DR lesions. Eyes progress from having no DR through a spectrum of DR severity that includes mild, moderate and severe NPDR.

Correctly identifying the stage of diabetic retinopathy in an eye enables us to:

- Predict the risk of disease progression and vision loss

- Choose appropriate treatment recommendations including follow-up interval.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy is the most advanced stage of DR. It is characterised by the growth of new blood vessels in the retina (retinal neovascularisation) and is linked with vision loss.

DR disease progression

Diabetic macular oedema

Diabetic macular oedema (DME) is an additional and important complication assessed separately from the stages of DR. DME can be found in an eye with any stage of diabetic retinopathy and can run an independent course. Eyes with DME are generally classified as being either non central-involved or central-involved.

DME disease progression

What to look for when classifying diabetic retinopathy and what to do

Non-sight threatening disease

No apparent DR

- Clinical signs: No abnormalities.

- What to do: Re-examine in 1-2 years. No referral to ophthalmologist required.

- What you could say to patients: “Diabetes can affect the inside of your eyes at any time. It is important that you come back in twelve months so we can examine you again. This will help to prevent you losing vision or going blind.”

Mild non-proliferative DR

- Clinical signs: Microaneurysms only.

- What to do (tailored for available resources): Re-examine in 6-12 months. In low resource settings re-examine in 1-2 years. No referral to ophthalmologist required.

- What you could say to patients: “Your diabetes is affecting your eyes. At the moment your vision is good, but we must check your eyes in 12 months’ time to see if these changes are getting worse. If the damage becomes severe, we will need to treat your eyes to stop the diabetes affecting your sight.”

Moderate non-proliferative DR

- Clinical signs: Microaneurysms and other signs (e.g. dot and blot haemorrhages, hard exudates, cotton wool spots). but less than severe nonproliferative DR.

- What to do: Re-examine in 3-6 months. In low resource settings re-examine in 6-12 months. Referral to ophthalmologist required.

- What you could say to patients: “Your diabetes is damaging your eyes. At the moment your vision is good, but we must check your eyes in six months’ time as it is likely that these changes will get worse. If the damage becomes severe, we will need to treat your eyes to stop the diabetes affecting your sight. Unless you are treated promptly, you risk losing vision or going blind.”

Severe non-proliferative DR

- Clinical signs: Any of the following signs – intraretinal haemorrhages (≥20 in each quadrant), definite venous beading in 2 quadrants or intraretinal microvascular abnormalities in 1 quadrant – and no signs of proliferative retinopathy.

- What to do: Assess within 3 months. Referral to ophthalmologist required.

- What you could say to patients: “Your diabetes has damaged your eyes quite severely, although your vision is still good. You are likely to need treatment soon to ensure that you don’t lose vision or go blind. We must check your eyes in six months’ time. However, if you think you may not be able to come then, we may treat your eyes now, so we can be sure you don’t lose vision later.”

Sight threatening disease

Proliferative DR

- Clinical signs: Severe non-proliferative DR and 1 or more of the following signs – neovascularisation, vitreous/pre-retinal haemorrhage.

- What to do: Assess within 1 month. Referral to ophthalmologist required.

- What you could say to patients: “Your diabetes has damaged your eyes very severely. Although your vision may be good, you are at great risk of losing your sight over the next year. You need urgent treatment to save your sight. Treatment will not improve your eyesight, but should preserve the vision you have.”

Diabetic macular oedema (DME)

Hard exudates are a sign of current or previous macular oedema. DME is defined as retinal thickening and requires dilated examination using slit-lamp biomicroscopy and/or stereo fundus photography.

Non-central-involved DME

- Clinical signs: Retinal thickening in the macula that does not involve the central subfield zone that is 1mm in diameter.

- What to do: Re-examine in 3 months. Referral to ophthalmologist required (laser resources required).

- What you could say to patients: “Your diabetes is damaging your eyes. At the moment your vision is good, but we must check your eyes in six months’ time as it is likely that these changes will get worse. If the damage becomes severe, we will need to treat your eyes to stop the diabetes affecting your sight. Unless you are treated promptly, you risk losing vision or going blind.”

Central-involved DME

- Clinical signs: Retinal thickening in the macula that does involve the central sub field zone that is 1 mm in diameter.

- What to do: Assess within 1 month. Referral to ophthalmologist required.

- What you could say to patients: “Your diabetes has damaged your eyes severely. Although your vision may be good at present, it is likely to get worse over the next year or two. You need laser treatment to stop your sight deteriorating. The treatment will not improve your eyesight, but should preserve the vision you have.”

Patient education at each examination should also be part of the protocol, encouraging people with diabetes to attend regular DR screening, manage their diabetes, and communicate with their general physician and endocrinologist. Counselling must also be provided for those with reduced visual function.

Reflection

The international classification system has been widely endorsed by most international authorities, including the World Health Organization, as a standard system for guiding evidence-based practice. What are the key strengths of this classification when communicating with persons with diabetes with no visual complaints?

Share this

Diabetic Eye Disease: Building Capacity To Prevent Blindness

Diabetic Eye Disease: Building Capacity To Prevent Blindness

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free