Disease Outbreak Prevention: What Is Outbreak Preparedness?

Share this step

Outbreak preparedness involves ensuring systems and plans are in place at a national level for detecting an outbreak early and implementing an effective response. This requires a multidisciplinary team and a multisectoral approach. Thorough preparedness requires more than simple ‘planning’, and includes simulations and exercises to identify and correct short-comings to ensure maximum operational effectiveness in the event of a real outbreak. An essential element of preparedness is to ensure organisations and individuals are clear about their roles and responsibilities. Outbreak preparedness should involve strengthening national core capacities as defined in the International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005. These are:

- Legislation and financing

- Coordination

- Zoonotic events

- Food safety

- Laboratory

- Surveillance

- Human resources

- Health emergency framework

- Health service provision

- Risk communication

- Points of entry

- Chemical events

- Radiation emergencies

All of these capacities are needed in order to strengthen a country’s public health capacity to detect and respond effectively to all hazards. This preparedness needs to encompass the entire health system, as effective health care capability is required alongside the public health response.

General outbreak preparedness enables countries to respond effectively to an outbreak of any disease or hazard that may cause a health emergency, known as an ‘all-hazard approach’. This is because common approaches can be used for responding to infectious disease outbreaks; CBNR (chemical, biological, nuclear and radiation) events; and natural disasters, that make it efficient to use one system of preparedness, while recognising the need for some specific plans for each type of event. One example of the common approach is the need to establish a functional public health emergency operations centre (EOC). Different disease outbreaks require specific plans and preparedness measures, such as:

- Vaccination programmes for measles;

- Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) for cholera;

- Preparing for diseases with a high probability of occurring e.g. an endemic disease with predictable seasonal peaks, such as Lassa fever in Nigeria or plague in Madagascar;

- Preparing for diseases that have a particularly severe health impact e.g. an influenza pandemic.

Finally, there is also a need to strengthen outbreak preparedness coordination and capabilities at an international level1. Examples include regional approaches such as the Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases and Public Health Emergencies and the continent-wide approach of the Africa CDC.

Why is preparedness essential to the outbreak response cycle?

The outbreak response cycle (Figure 1) defines the key steps needed for an effective response. The cycle should be continuous: outbreak preparedness provides a strong foundation for early detection enabling a prompt and effective response, and the learning from this process informs preparation for future outbreak detection and response to strengthen the system in advance of the next outbreak.

Figure 1 Cycle of Outbreak Preparedness & Response

Rationale For & Advantages of Preparedness

In order to prevent and contain outbreaks, all countries and international organisations should be adequately prepared to detect outbreaks early and respond promptly and effectively. However, in most countries there is under-investment in outbreak preparedness and an overreliance on outbreak response. In part, this is because effective preparedness results in no, fewer or less severe outbreaks. This may cause complacency among policy makers and a consequent challenge in mobilising the necessary resources to prevent and detect outbreaks. The focus on response rather than preparedness can be very costly, both in terms of human lives and financial costs. For example, it is generally agreed that inadequate preparedness during the global AIDS pandemic in the 1980s, and during the 2013-16 outbreak of Ebola virus disease in West Africa, led to delays in response and substantial human and financial costs2. The Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework for the Future estimated that the costs of implementing robust outbreak preparedness measures globally would be less than $5 billion annually, which is far less than the cost of responding to and controlling a major disease outbreak or pandemic2. Last week in the step on the global architecture, we saw that each of the recent outbreaks of SARS, Avian influenza, Ebola and Zika cost more than this annual figure.

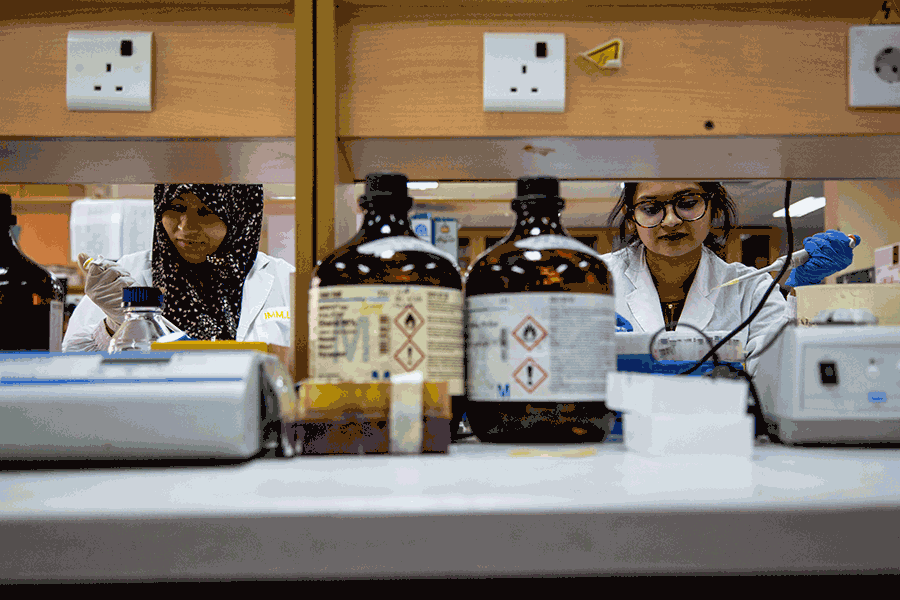

Logistic support and mobile laboratory vehicles prepared for deployment, Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, Abuja, Nigeria

© Louis Leeson/LSHTM

How do you develop a system for being prepared?

There are a number of key considerations in outbreak preparedness:

- All individuals and organisations involved in the detection and response stages should be clear on their own and others’ roles and responsibilities. This is best achieved by engaging all stakeholders at an early stage and collaborating in the development of preparedness plans.

- Communications within and between organisations involved in outbreak response should be established as part of the preparedness plan. This includes planning for how and when outbreak-related information should be communicated and shared, for example surveillance data and laboratory results. Particular consideration should be given to any barriers to communication between organisations, and how sensitive data (e.g. patient-identifiable information) will be shared.

- Plans and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) should be developed, shared, and tested. Testing though desk-top and simulation exercises is an important step in order to identify any barriers to implementation of the plan, for example inadequacies in communication mechanisms. Planning should take into account the limitations of the existing systems and infrastructure, while at the same time considering priorities for systems strengthening. This may, for example identify single points of failure, pinch points and bottlenecks, or the need for surge capacity.

- Logistics during an outbreak require planning and expertise and should be integral to the preparedness plan. Logistics functions may include the maintenance and distribution of vaccines; handling and managing the transport of infectious substances for laboratory testing; and coordinating operations during outbreaks3.

- Security of staff involved in the response, including biosecurity for laboratory staff handling dangerous pathogens, requires advanced planning to ensure the correct equipment, resources and training are in place.

- An important aspect of the IHR is the obligation for all parties to develop, strengthen and maintain core public health capacities for surveillance and response. Therefore, strengthening IHR capabilities is a crucial element of outbreak preparedness. Analyses of the West African Ebola outbreak identified that a lack of compliance with the IHR was a significant failure in the response2.

One Health

As we have seen earlier in the course, the World Health Organization defines One Health as “an approach to designing and implementing programmes, policies, legislation and research in which multiple sectors communicate and work together to achieve better public health outcomes,” in particular in the areas of food safety, the control of zoonoses and combating antimicrobial resistance (AMR)4. This collaborative approach can support earlier detection and more effective outbreak response, and should be built in to the preparedness plan.

Human and veterinary sectors working together and sharing information is particularly important, for example, an outbreak of a pathogen detected in animals can be prevented or contained by reducing animal-to-human transmission. For example, vaccination of livestock for Rift Valley Fever and restricting their movement can prevent outbreaks in both livestock and humans. This is of particular concern for emerging human pathogens, 70% of which come from animals5.

Outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, such as Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi (which causes typhoid), are a particular threat to human health. Collaboration between the human, animal and environmental sectors is needed in order to reduce the development of AMR.

Outbreak preparedness is an essential component of the outbreak response cycle. This is a key requirement of the International Health Regulations in order for countries to be able to provide health security for their citizens. Preparing for outbreaks and other hazards needs careful planning and adequate resources, but when it is done well it has been shown to be highly effective in reducing the human and economic costs of outbreaks.

Share this

Disease Outbreaks in Low and Middle Income Countries

Disease Outbreaks in Low and Middle Income Countries

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free