Campfire CPD in the Cloud

Share this step

So far on this course, we’ve explored the ways in which technology can support pupil learning and school efficiencies. Yet to be considered is how it can enable staff to engage in their own learning in flexible and accessible ways.

Before we read an article from David Rogers, let’s take a look at the advantages technology has that work for teacher and staff learning:

-

Time to think

Effective CPD often exposes us to new perspectives that can feel discomforting. We can encounter something that makes us question our practice: ‘Was I wrong all along?’. Conversely, we can dismiss a finding too quickly when bias clouds our judgment. Learning online can allow time to return to ideas we find problematic, after having taken time to think. Having time and space for reflection in between learning modules can allow us to engage with research findings and new perspectives in measured ways, in order to more effectively judge whether they hold answers for our particular context.

-

Building a community

A climate of trust between participants is a vital component for effective learning online. Use of social media by teachers suggests a desire to develop a powerful personal learning network beyond the confines of the school environment. When facilitated successfully, participants in an online community can feel encouraged to take risks, discuss successes, failures and challenges, and experiment in their classroom practice. While these might be important outcomes for any professional development, they are particularly important for early-career teachers.

-

Flexible access

In a school where staff are on different contracts and working patterns, or even on parental leave, technology can enable learning for everyone. The member of staff who doesn’t work on a Wednesday might still be able to access a discussion forum, video or slides related to the twilight CPD that took place on a day when they are working. Those on parental leave can access some of their keep in touch days remotely by accessing their department’s shared documents related to the new curriculum on the cloud platform.

In this article, David Rogers, a geography teacher and senior leader, shares how the cloud can create the perfect conditions for ‘campfire CPD’.

There are two key objectives for using technology in schools. The first is to learn about technology, and the second is to use technology to enhance the learning of other knowledge (Ashman, 2018). I would argue that the methods outlined below help teachers to enhance the learning of other knowledge. Where one of the main questions we ask is ‘how does this enhance learning?’, the use of cloud computing can free up teacher time and support their development.

Technology can help, although not necessarily through its role in the classroom. Where technology really has the power to transform education is in how it enables busy teachers to communicate, structure the curriculum and free up time to talk about teaching; this in turn helps to ensure that young people amass a body of specific, declarative and procedural knowledge in a carefully planned way (Sherrington, 2018). From my own experience, here are four ways in which cloud computing (a combination of Google Docs and Microsoft’s OneDrive) has been used to allow teachers to focus on the main thing: talking to teachers about teaching, whilst integrating all that we know about cognitive science and curriculum design.

1. Create a dynamic and living curriculum that supports teachers to deliver high quality sequences of lessons. The key documents for any department are the curriculum and schemes of work. When I started teaching, these were often kept in folders that were rarely accessed. By placing the entire curriculum ‘in the cloud’, all teachers in the Geography department could access them. This had the effect of transforming a standard scheme of learning into a dynamic document, and novice teachers were able to benefit from the knowledge and experience of colleagues. In addition, evidence-informed principles such as interleaving, spacing and cognitive benefits such as retrieval practice were brought to the fore.

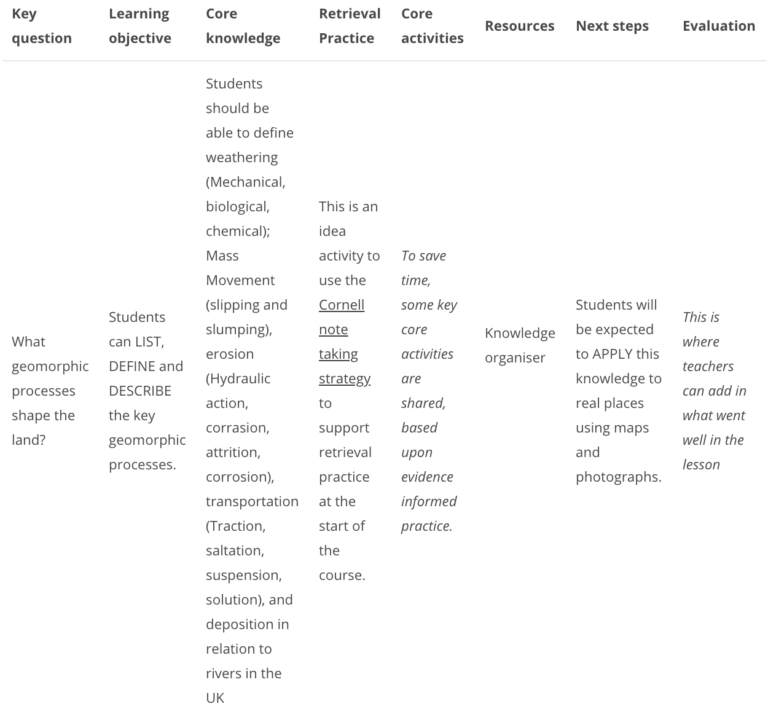

An example proforma can be seen in Figure 1.

Students will be expected to APPLY this knowledge to real places using maps and photographs. This is where teachers can add in what went well in the lesson

Some fear that such a system results in robotic teaching, but I have found that teaching is enriched and outcomes improve. Indeed, as the document is ‘owned’ by the department, extra ideas and resources can be added at any time, feeding into departmental discussions. Furthermore, trainee teachers and those recently qualified fed back that this supported them in understanding what made effective teaching.

2. To communicate departmental meetings When I became a Head of Geography, I soon realised that department meetings were filled with procedural administrative tasks rather than being focused on our core purpose: to make the teaching and learning of geography the best it can be. In order to solve this, a Google Document was created and shared. I set out the agenda ahead of time, and expected staff to access and contribute when it was most appropriate (for example during a PPA time). Examples included:

- Lesson learned from assessment points

- Open evening ideas

- Book monitoring

The key was to make the document available at all times and provide time to engage with it, in this case during a morning department operational meeting. The result is that, during departmental meeting time, all of the information has already been gathered so that detailed discussions can take place around developing the curriculum. Other activities include demonstrating explicit instruction, making curriculum links and designing effective interventions. It is amazing what can be achieved in a departmental meeting when you take away the administrative burden.

3. To improve line management communication Line management meetings are an important part of school but, like departmental meetings, the use of time can be inefficient. By setting up a proforma on a cloud platform and sharing it between line manager and the individual staff, information and ideas can be shared before a meeting so that valuable face-to-face time is used for mentoring, coaching and in-depth discussions. Furthermore, as the document is ‘owned’ and authored by all, either party can add agenda items, discussion points, or make decisions.

4. To manage resources so that teachers spend time planning lessons rather than creating resources Teachers spend a vast amount of time creating resources. As a Head of Department, I decided to invest some money in a departmental Dropbox account. This allowed for shared access to high quality resources that had already been created. Where copyright didn’t permit this, a clear link is given within the scheme of work. Again, this isn’t about developing a robotic, singular approach to teaching, but rather eliminating the ‘busy’ tasks of creating resources. Sharing resourcing in this way enables teachers to focus on planning for their classes and for the learning, rather than creating tasks.

The effect of this has not only been to raise standards, but to enable teachers to talk about teaching to other teachers. Fundamentally, using cloud computing allows us to focus on identifying evidence-informed approaches without over-burdening teachers with the need to access and interpret a wide range of academic literature.

References

Ashman, G (2018) The Truth about Teaching: An evidence-informed guide for new teachers. London: Sage Publications.

Burns, R (2018) Applying the ‘powerful knowledge’ principle to curriculum development in disadvantaged contexts. Impact. Available at: https://impact.chartered.college/article/applying-powerful-knowledge-principle-curriculum-development-disadvantaged-contexts/ (accessed 7 January 2019).

Killian, S (2017) Hattie’s 2017 Updated List of Factors Influencing Student Achievement. Accessed: http://www.evidencebasedteaching.org.au/hatties-2017-updated-list/ (accessed 11 October 2018).

Kime, S (2017) From intentions to implementation: establishing a culture of evidence-informed education. Impact. Available at: https://impact.chartered.college/article/kime-culture-evidence-informed-education/ (accessed 7 January 2019).

Sherrington, T (2018) What is a knowledge-rich curriculum? Impact. Available at: https://impact.chartered.college/article/what-is-a-knowledge-rich-curriculum/ (accessed 7 January 2019).

Young M, Lambert D, Roberts C, et al. (2014) Knowledge and the Future School: Curriculum and Social Justice. London: Bloomsbury.

This article was originally published in Impact, award-winning peer-reviewed termly journal of the Chartered College of Teaching

Once you’ve reflected on the points raised with other course participants, click the ‘Mark as complete’ button below and then select ‘Discuss your learning’ to share reflections on this week’s learning with other course participants.

Share this

Leadership of Education Technology in Schools

Leadership of Education Technology in Schools

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free