Record types: state and legal

State records

The Scottish Parliament evolved during the medieval period from the king’s council of bishops and earls.

The first identifiable parliament emerges in 1235 as a ‘colloquium’ with a political and judicial role. By the early fourteenth century knights and freeholders were attending, as were burgh commissioners by 1326. Consequently, the parliament consisted of ‘three estates’ of clerics, tenants-in-chief and burgh commissioners sitting in a single chamber.

From 1567 Catholic clergy were excluded, but Protestant bishops continued to sit until their abolition by the Scottish Covenanting regime in 1638 (to be restored again in 1661 and abolished once more in 1690).

Another innovation occurred in 1587 when the lairds of each shire were granted the right to send two representatives. However, the franchise was limited to those who possessed a forty-shilling freehold (i.e. they held land directly from the king which had an annual rent of forty-shillings or above).

Riding of Parliament c. 1685 by Nicholas de Gueudeville (1653-1725) [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Riding of Parliament c. 1685 by Nicholas de Gueudeville (1653-1725) [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

In its existence to 1707, the Scottish Parliament acquired significant powers. For example, it was the forum whereby consent was secured for taxation. It also exercised an influence over justice, diplomacy and war, and passed legislation covering a range of political, ecclesiastical, social and economic issues. The business of parliament was also undertaken by ‘general council’, and later, the ‘convention of estates’, which, although lacking the authority of a full parliament, engaged in policy-making.

The Scottish Parliament was held in a variety of locations throughout its history, but Edinburgh became the undisputed centre of government by the mid-fifteenth century. However, there was no dedicated parliamentary building until the completion of Parliament House in 1639.

Although the earliest surviving parliamentary rolls date from 1293, there are few original records earlier than 1466. They are now housed in the National Record of Scotland. Over a ten year period the Scottish Parliament Project based at the University of St Andrews transcribed and digitised these records. They can be found at: Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707

In addition to the parliamentary papers, the records of the Scottish Privy Council provide valuable insights into the early modern era.

Like the Scottish Parliament, it developed from the king’s council (the curia regis) of royal officers, and is known to have existed in the thirteenth century. However, little is known of its function until the fifteenth century, where it can be seen operating as an advisory, executive and judicial body. By 1490 it was known as the ‘secret’ or privy council, with a separate register recording its affairs from 1545. After the Union of Crowns the privy council became central to the administration of Scotland.

Although largely displaced by the Covenanting regime during the British Civil Wars, it was revived by Charles II and survived until 1708. As with the parliamentary rolls, the registers and minute books of the Scottish Privy Council are located in the National Records of Scotland. They provide a fascinating picture of the day-to-day administration of the country and are especially detailed after 1660 in their accounts of Scottish society.

Legal records

In the medieval period, judicial matters in Scotland were often handled by parliament and the privy council. They were also handled by justiciars who were appointed by the crown for judicial and administrative purposes. This office originated in the twelfth century and evolved into the current lord justice-general – the head of the high court of justiciary.

In addition, the early modern period saw the crown issue commissions of justiciary in order to tackle particularly pressing problems of crime or disorder. However, as might be expected, the system was open to abuse by nobles looking to settle feuds or promote their own aggrandisement. Indeed, in Scotland the administration of justice was largely delegated to the nobility, whose barony or regality courts gave them substantial power and authority until their abolition by the parliament of Great Britain in 1747. Only the four pleas of the crown – murder, robbery, rape and arson – were retained as areas where the crown had exclusive jurisdiction.

A specific judicial body was created in 1532 when James V founded the College of Justice. It consisted of 14 ordinary lords (known as ‘senators’) who were supplemented by an indefinite number of supernumerary judges (the ‘extraordinary lords’). The College dealt with civil law and did not dispense criminal justice until the High Court of Justiciary was incorporated into the College in 1672.

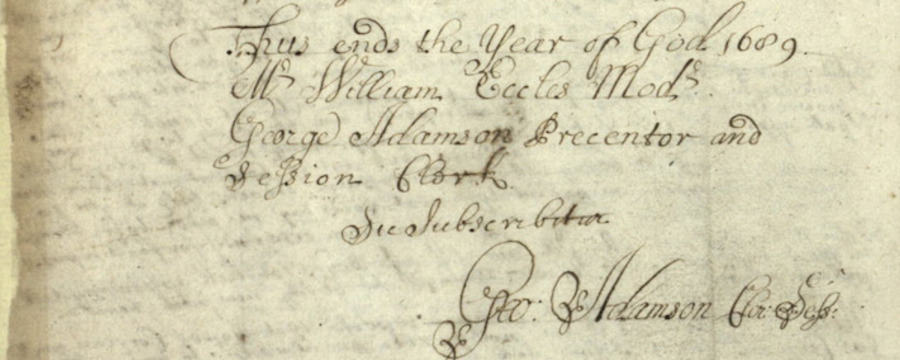

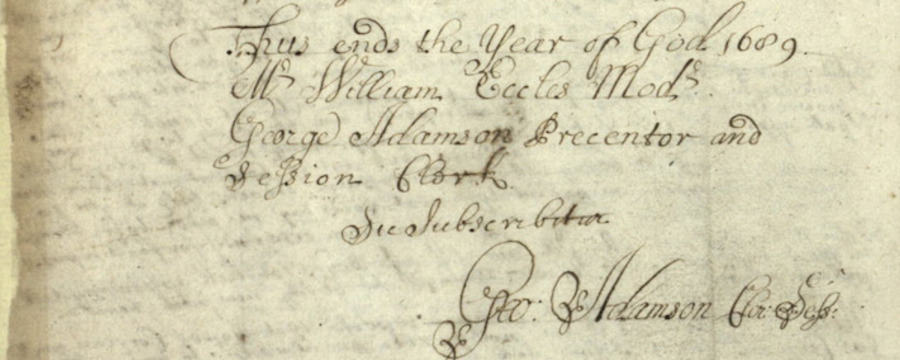

A constituent part of the College is the Faculty of Advocates – an independent body of lawyers admitted to practice as advocates before the courts of Scotland. Although existing since at least 1532, it may possibly predate the creation of the College. The library of the advocates – formally inaugurated in 1689 and effectively Scotland’s national library by the 1850s – is widely regarded as one of the most important libraries in the British Isles. Much of the material has since been deposited in Parliament House and the National Library of Scotland, with the latter holding around 750,000 items from the Faculty’s non-legal collections.

The extant sheriff court records, most of which cover the early modern period, are also available for consultation. The majority are housed in the National Records of Scotland, with the notable exceptions of Kirkwall, Lerwick, Orkney and Shetland, which can be found in local archives. As with the other offices noted above, the sheriff can be dated to the medieval period. His purpose was to exercise and maintain royal authority in specified districts against the rival power of the Scottish aristocracy. However, as the appointments were usually local lords or lairds whose office became hereditary, royal and aristocratic authority could be indistinguishable. The hereditary sheriff was assisted by a sheriff-depute with legal training and expertise. As well as dealing with a range of civil and criminal cases, the sheriff court was also the body through which the lairds nominated their representatives to the Scottish Parliament.

Share this

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free