Early Modern Scotland: Estate, Burgh and Church Records

Estate records

Scotland retains a number of archives or manuscript collections which belong, or belonged, to aristocratic families.

Some remain in private hands while others have since been bequeathed to specific institutions. Examples include the Argyll Papers – a collection of family and estate papers belonging to the Campbell dukes of Argyll – which are currently housed in Inveraray Castle and among the most important privates archives in Scotland, if not the British Isles:

The records of early modern aristocratic families and their estates are multifarious and not easily generalised. However, some tentative suggestions may be made. First, there are often extensive collections of correspondence which, among many things, reveal intra- and inter-family relationships. The legal framing of these relationships can also be found in bonds of alliance, marriage contracts and inheritance deeds. Many families also kept manuscript genealogies – blending fact and fiction – which stressed their ancient lineage, virtuous conduct and regal connections.

Above all, estate records are concerned most with estate management. Notable here are rental rolls and leases (‘tacks’). While usually no more than a summary of income, some may provide details of the tenantry, the name, extent and value of the land, the year in which the lease began or was renewed and supplementary payments in kind or labour to the landowner. Furthermore, the factors – those who managed an estate on behalf of a landowner – often kept records which shed light on the day-to-day running of an estate. As landowners often erected buildings on their property, such as storehouses or mills, additional details may also be gleaned on agriculture, fishing, forestry and extractive industries such as coal-mining. Meanwhile, the consumption and expenditure of an aristocratic family, alongside the army of staff which it employed, can be traced in surviving household ledgers.

Burgh records

The earliest Scottish burghs date from the reign of David I (1124-53). He sponsored the growth of towns as a means of fostering trade and increasing crown revenues.

The burgh’s privileges and obligations, touching on trade and the right to hold markets, were enshrined in a charter granted by the king or another feudal superior. In return, royal burghs made annual payments to the crown of the rents of burgh properties and trade customs. This became a fixed annual sum over time. Any surplus money was then paid into a ‘common fund’ for the benefit of the burgh.

The burghs were governed through burgh courts, which were originally a gathering of ‘all the good men of the community’. Gradually the court met in a judicial capacity and came to consist of bailies only, with the town council (provost, bailies and councillors) attending to administrative business. It was the merchants who came to dominate the magistracy of the towns as the royal charters were effectively mercantile documents. It was they who brought in the largest part of the burgh revenues – the burgh customs.

Different types of burghs exhibited a wide variety of systems of government until nineteenth century legislation imposed uniformity. The 1833 Burgh Reform Act also swept away the corruption of council oligarchies by introducing elections. Royal burghs still retained certain privileges, including their own registers of sasines, but in the twentieth century all except the largest lost powers and functions, mostly to the county councils.

In the early modern period, there were three types of burgh: the royal burgh, the burgh of regality and the burgh of barony. The royal burghs were given their privileges directly by the crown and acquired a monopoly over domestic and foreign trade. The burghs of regality were created by vassals of the crown while the burghs of barony were granted by barons or landholding clerics. The burgh records of Scotland are not uniform in their style or scope. With the notable exception of Aberdeen (Aberdeen City Archives) there are few significant burgh records pre-1500.

However, there are a variety of surviving records for the early modern Scottish burgh. These include charters, registers of deeds (relating to debt, property, apprenticeships and other contracts), registers of sasines (burgh registers instituted by an act of parliament in 1681), account books, court books, protocol books and council minutes. There are also extant burgess rolls which record the burgesses of a burgh.

The burgesses were those merchants and craftsmen who constituted the free men of the burgh, although burgess tickets were also issued to outsiders who performed particular services for the burgh – often, but not always, drawn from the local aristocracy. All others were classified as ‘indwellers’ and treated as strangers.

While burgh records are spread across local and national archives, the National Records of Scotland hold a substantial number of the records relating to early modern trades and crafts which were promoted and defended by guilds. For example, manuscripts survive for bakers (‘baxters’), blacksmiths (‘hammermen’), brewers (‘maltmen’), butchers (‘fleshers’), dyers, shoemakers, tailors and weavers.

Church records

The early history of Christianity in Scotland, as with the early history of Scotland more generally, is very difficult to trace with accuracy. Christianity in southern Scotland is presumed to have been introduced by the Romans, although it may not have survived the advance of pagan Anglo-Saxons into the Lowlands. The conversion of the Picts is believed to have begun between the fifth and seventh centuries. There were also missionary traditions associated with the saints Ninian, Kentigern and Columba of the sixth century.

Gaelic forms of monasticism did exist prior to the introduction of a Benedictine abbey at Dunfermline around 1070. With the settlement of Normans in the twelfth century, a diocesan structure of church governance emerged. As a result, the Archbishops of York and Canterbury each claimed ecclesiastical superiority over the church in Scotland – a situation which was unresolved until a papal bull of 1192 asserted the independence of Ecclesia Scoticana as a ‘special daughter of Rome’. While papal bulls, cartularies and other miscellaneous items have survived, the records of the medieval Scottish church are primarily from the fifteenth and early sixteenth century.

Following the Reformation in 1560, the Church of Scotland was transformed. Based on the experience of Geneva, a presbyterian structure of hierarchical courts was developed to govern the church and which continues to operate today. They range from the kirk session at parish level through to the presbytery and synod. The supreme court is the General Assembly, which is chaired by an annually nominated moderator. Episcopal oversight was a hotly contested issue until the abolition of prelacy in 1690, with the Scottish Episcopal Church becoming a distinct entity in the eighteenth century.

A further series of secessions in the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries led to the creation of several other presbyterian churches. Those which continue to exist include the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland, the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland, the United Free Church and the Free Church of Scotland. In addition to Methodist, Quaker and Unitarian churches, the majority hold their records in the National Records of Scotland. The archives of the Catholic Church of Scotland are administered by its own dedicated institution:

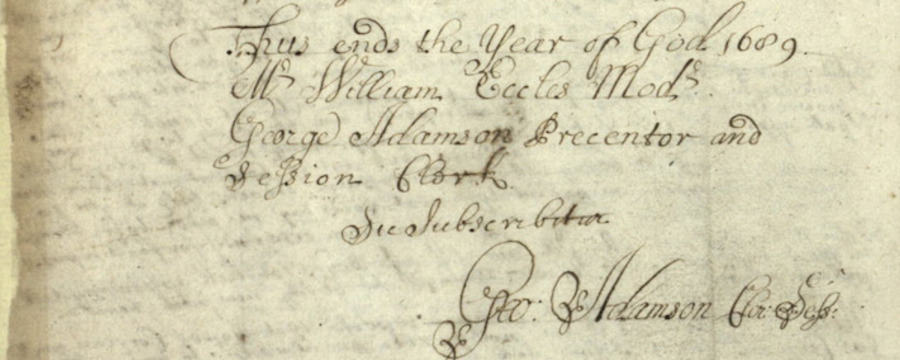

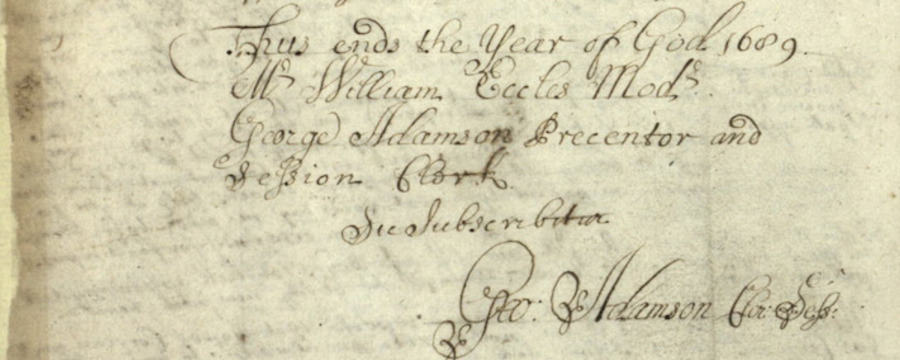

The records of the courts of the Church of Scotland are amongst the most useful resources available to early modern historians. The National Records of Scotland is the official repository for these records. The records consist of the minutes and accounts of the courts, providing a remarkably lucid, if sometimes disturbing, picture of everyday life in Scotland. These records amount to more than 25,000 volumes – around five million pages. They will be discussed in greater detail as you get to grips with early modern Scottish palaeography.

Share this

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free