Early reformation Perth: The kirk session and its personnel

Share this step

l. Ministers

Perth’s first protestant minister, John Row, had been as zealous a Catholic as he would be a protestant. Educated in the grammar school of Stirling, then St Leonard’s College in the University of St Andrews where he matriculated in 1544, he studied canon law as part of his MA degree and then served as an advocate in the consistory court of St Andrews. In 1550 he became an agent for the Scottish clergy at Rome, earned a civil law degree at Padua, and entered the service of Pope Paul IV. In about 1558, the pope sent him back to Scotland as a nuncio to assess alarming reports of protestant success there. He was also charged to look into an alleged miracle at St Alaret’s Chapel in Musselburgh. It was in the course of this investigation that he became convinced the protestants had got it right, that the Musselburgh miracle was only one of many outlandish inventions by the Roman clergy designed to enthral the people to superstition. He joined the Reformed cause and became one of the six ministers appointed by the Lords of the Congregation to write a new confession. He was also one of the authors of the First Book of Discipline and a contributor to the Second Book. Initially installed as a preacher in Edinburgh, on 17 July 1560 he was translated with the consent of that congregation to the charge of St John’s kirk in Perth, where we can be sure he introduced the provisions of the First Book. Row was allotted the handsome annual salary of £200 and a chalder [about one hundred bushels] of oats, though he seems to have had problems collecting from the local lairds, who were responsible for payment of a large portion of his stipend and teinds: some of his 1574 payment was still in arrears in 1577. He had similar problems with the miserly town council, responsible for his house rent. He boarded in his home several gentlemen’s sons, students at the town grammar school, whom he instructed in Hebrew and Greek, and required to speak only French in his home (one of his sons reported that Row’s children were introduced to Hebrew at age four or five). A zealous and frequent preacher, he also continued to serve the protestant cause at the national level: he was moderator of the General Assembly in 1567 and 1576–78, and superintendent of Galloway. He published, in addition to his contributions to the Books of Discipline, a treatise no longer extant called Signes of the Sacraments. He held, together with Perth, the vicarages of Twynhohn and Terregles in Galloway.

Row married Margaret Beaton, daughter of John Beaton of Balfour, and proceeded to found a protestant clerical dynasty. Between 1562 and Row’s death on 16 October 1580, the couple had twelve children, eight of whom survived to adulthood. Among them were five ministers: James of Kilspindie, William of Forgandenny, John of Carnock, Archibald of Stobo, and Cohn of St Quivox. One of the two daughters, Catharine, married an Edinburgh merchant; the other, Mary, married Robert Rynd, minster of Longforgan. Perth’s parishioners proved ungenerous to his widow and children, too, as they had to petition the kirk session and the burgh council for overdue payment of their allotted pensions.

The burgh’s second protestant minister, Patrick Galloway, was translated from Foulis Easter to succeed Row. Called in November 1580, he finally arrived in Perth the following April and was admitted to the parish ministry at some point after the twenty-fourth. His first few years in his new parish were eventful. His fiancee, Matty Guthrie of Perth, whom he would marry in 1583, was the victim of a vicious and probably quite groundless slander by an embittered object of the elders’ moral discipline. Quite apart from this incident, Galloway also ran into serious political trouble, at about the same time. This stemmed from his close association with the radical presbyterian ministers led by Andrew Melville, and with Lord Ruthven (by 1581 the Earl of Gowrie). A staunch presbyterian and inveterate political foe of the Regent Arran and his episcopalian cohort, Gowrie decided in 1582 to kidnap the sixteen-year-old king, then in Perthshire on a hunting trip, for safe (presbyterian) keeping in Ruthven Castle, with brief sojourns in Cowrie’s Perth townhouse, and in Stirling. Joined by the earls of Mar, Glencairn, and Lindsay, the ‘Ruthven Raid’ succeeded in keeping the king in custody for the better part of a year. James then escaped to Fife and pronounced the Raid an act of treason. Unfortunately for the town, Gowrie was provost of Perth at the time, so the magistrates were understandably quaking in their boots until, after some mild harassment, the young king exonerated the citizenry, thanking them for their (rather illusory) support against their provost. Although he banished the other lords, James exercised remarkable mercy towards Ruthven, who lived to plot again in 1584. This time, with Mar, Angus, and Glamis, he planned a march on Stirling, but was found out and arrested at Dundee. He was taken into custody by Arran’s troops, tried in Edinburgh, and duly executed. The unfortunate Mr Galloway was suspected of participation in the Stirling conspiracy, probably on the slim grounds that he had signed a complaint against episcopacy presented to the king at Perth just before the Raid. He fled to England in May 1584, joining James Melville in London, then serving with him in Newcastle. He returned to Perth in November 1585, and by June of 1589 his reputation had been sufficiently rehabilitated that James appointed him a royal chaplain. In 1607 he was translated to St Giles, Edinburgh.

John Howieson of Cambuslang served as minister in Galloway’s place from 23 November 1584 to at least mid-August of 1585. Howieson had his own problems in his home parish, perhaps motivating his move to Perth. In June of 1580 he had brought suit against his parishioners for their failure to pay the teinds and rents of the parsonage. His complaint charged that the people would not ‘answer nor obey him of the same without they be compelled’. The Lords of Council found for the plaintiff and ordered the parishioners to pay up or be warded in Edinburgh Castle. Things in Cambuslang cannot have been very comfortable for the minister, so that a sojourn in Perth must have seemed a welcome respite – were it not for the fact that Perth was then in the midst of a devastating outbreak of the black death. Then again, things were never very comfortable for Howieson, so outspoken was his opposition to episcopacy. He had been brutally attacked by the provost and bailies of Glasgow in the pulpit of the High Kirk for refusing to allow Robert Montgomery of Stirling to preach, Montgomery being in his view ‘an infamous [episcopalian] man, a monster’. Radical presbyterianism got him imprisoned at various points in his life in Perth’s Spey Tower, Falkland Palace, and Edinburgh Castle, and caused parliament in 1587 to revoke his presentation to Cambuslang. Perth’s parishioners may well have given a sigh of relief when Galloway returned in 1585 and sent Howieson home.

Perth had only a single minister until 1595, when William Cowper arrived to assist Galloway’s successor, John Malcolm (installed in 1591). With more than four thousand parishioners even after the devastating plague of 1584–85, the only way Galloway could hope to fulfil his duties was with the active assistance of the twelve lay elders. The session proved equal to the task.

II. The session

Perth’s elders were, like members of the town council, a self-replicating group, despite the order of the First Book of Discipline that elders and minister be elected by the people. The session’s elections were, like the council’s, held during Michaelmas season and were quite closed: the minutes state clearly, ‘the assembly has chosen’ the new elders. The elders then directed the minister to announce the names of those elected the following Sunday from the pulpit so that the new men might ‘lawfully receive their offices and be warned to the faithful execution of the same’. That said, this public announcement then provided an opportunity for the congregation to object ‘if any of them had [something] to oppose against the same’, and it is clear from events in other parishes that lay people did occasionally exercise their veto power, particularly after 1581 when they could appeal to presbyteries. Given that John Row was one of the authors of the First Book of Discipline, it is likely that the congregational vetting of new elders would have had some meaning in Perth; nevertheless, the session minutes regularly record that ‘nothing was objected or opposed’, and the new elders duly took their oath of office and were installed. Either congregational veto power was as much a fiction as the people’s election, or sessions managed generally to choose well-regarded successors.

Despite the oligarchic bent of the system, however, the Perth session was not the tiny, closed elite that we associate with early modern urban government. Indeed, a remarkable number of men, from an impressively broad swathe of urban society, served on the parochial court. In the fourteen-year period of the text transcribed here, eighty-one different men served as elders. In some years there was an almost complete turnover of the session at the fall election. Of the total, about equal numbers were merchants and craftsmen (thirty-eight and thirty-four, respectively), an additional five were notaries (one also a schoolmaster), one was a local landed gentleman, and three are of unknown occupation. The turnover, the number of men serving, and the equality of craftsmen and merchants, may be unique in Scottish urban sessions; however, further research in other parish records will obviously be required to determine this. By the end of the century, the session s size would grow to about seventeen, with the number varying a bit from one election to the next. After 1592 there were generally two ‘landwart’ elders to represent rural areas around the town, one designated north or west, the other south; and as the town’s suburbs expanded, elders were added for them as well.

Twelve deacons were elected at the same time as the twelve elders, from the same four sections of the town; however, the deacons did not sit in session meetings and are not central to understanding the operation of parochial discipline or administration except in their particular area of responsibility, the collection and distribution of alms. Beyond this, and their defined ceremonial roles in communion celebrations, they get scant mention in the session minutes. A significant number can be identified as craftsmen, but (unlike the elders) the majority cannot be identified with any certainty at all from surviving records, suggesting that their social status was notably lower than that of the elders, corresponding to the lesser importance of their office in the kirk. A few went on to serve later as elders, but this was an exception to the rule; for the most part, deacons remained in their ecclesiastical status just as in their social estate.

III. Other officers

At its annual selection of successor elders and deacons, the session also named two masters of hospital. Only rarely did these men also serve as elders or deacons. Initially they were salaried; however, in the 1585 plague year when not a penny could be spared, the office became permanently non-stipendiary. Hospital masters were responsible for collecting annual rents due to the hospital and for administering the institution; they worked closely with the deacons who collected alms in the kirk, with the elders who distributed those alms as ‘outdoor relief’ to the poor outwith the hospital, and with the bailies and council.

Election tallies generally report also the choice of a kirk ‘officer’, who provided such services as summoning people to appear before the session, opening the church for weddings, whipping dogs out of the kirk during service time, securing materials to build and repair burial ground walls, and preventing children from breaking windows. From 1577 this was Alexander Jhonston, whose stipend of 40s is specified 6 October 1578. He would be succeeded by James Sym, then Jhon Ronaldson, both of whom also served as deacons (Sym for many years, 1577–80, and 1585–89), William Ross in 1582, and Jhon Jak (admonished for negligence in 1585, but retained in service). When the deacon Sym also served as kirk officer, he had among his duties the annual reporting of his accounts for poor relief and the keeping of a book (now lost) in which to keep records of relief. Sym’s stipend rose to 33s 4d for Whitsun term, presumably because he also served in the song school and had to ‘sit with the choristers and to his duty’ in church. Ronaldson received only 13s 4d as his base stipend, but kirk officers collected additional fees for extra duties: Ronaldson got for each Sunday marriage ‘a day’s meat’(whether in the form of groceries or a dinner invitation is not clear), and Jhon Jak got sixpence for each marriage contract. Jak was still serving as kirk officer in 1590, despite his stipend being by then years overdue.

Other officers were appointed for indeterminate periods rather than elected annually. A bell ringer doubled as sexton; in this period Nicol Ranaldson (referred to in the session books as ‘Nicol Bellman’) filled the post until he was incapacitated by age. The importance of the bellman, who rang the waking and curfew bells for the town as well as the bells calling the congregation to attend services, is clear from the minutes of 18 February 1583. In addition to bell-ringing, he was charged to ‘keep the kirk from bairns, dogs and tumults’ and to ensure that it was properly lighted for services. The bellman was also responsible for ‘daily tempering of the clock’ in the kirk. From 1585 the session appointed another man to shave the heads of fornicators as part of their punishment: James Petlandy did this job in the 1580s for 12d per head and an annual stipend of 40s.

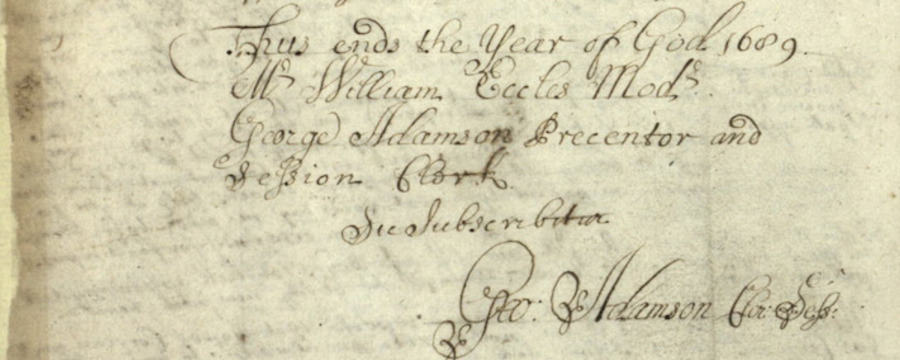

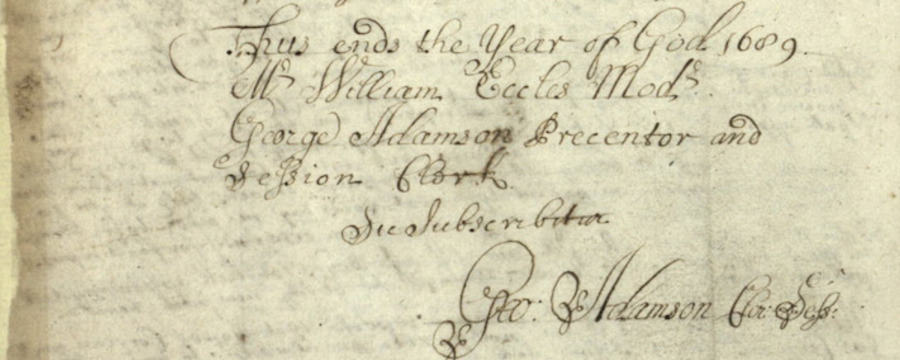

More important were the readers and the clerks of session – often but not always the same person. The reader in the 1570s was Jhon Swenton, who in addition to reading the Scriptures for an hour before each Sunday service acted also as cantor to line the psalms, as session clerk (until 1578), and as master of the song school (although he was temporarily dismissed in 1582 for poor service). For reading and secretarial services the stipend was ten merks; Swenton also periodically received a set of new clothes. In February of 1582 he was succeeded as reader by William Cok, who would be elected deacon two years later. He had already been replaced as clerk by Walter Cully (1578–79), then James Smyth (1580–81), and in 1581 William Cok again. The reader from at least 1589 was William Balnavis, whose stipend was apparently paid only very irregularly, as can be witnessed by the sessions order to the hospital masters to pay him when his ‘evil payment’ had led to his ‘necessitie’. On the other hand, his stipend was a substantial forty merks in 1589, and forty pounds in 1590. By that year the keeper of the parish register, and presumably of the session book as well, was Jhon Cok.

The session clerk took minutes at the elders’ meetings, wrote out depositions and testimonials (for example, of repentance completed, or of the manners and morals of parishioners moving to other congregations), corresponded with other sessions and the presbytery, and kept the minute books. He was also responsible for the registers of baptisms, marriages and burials ordered at the Reformation. He received a ten-merk stipend and additional fees for particular tasks – twelve pence for each testimonial, for instance. Regular payment of the stipend could be as problematic for him as for the minister, however: Swenton served for at least a year without pay, and the guildry book records a payment to James Smyth on 6 September 1582 for his 1581 stipend, nearly a year late. Cok’s stipend was so far in arrears at Lammas 1583 that in the following year he took legal action against the hospital master, who was at that time responsible to the session for his remuneration. The outcome seems not to have satisfied him, for in 1586 the session in turn had to pursue him legally — even deposing him from office and ordering him imprisoned — for refusing to turn in the minute book and baptismal register. These documents may well have been serving as hostages for back pay.

Extract from Margo Todd (ed.), The Perth Kirk Session Books 1577–1590. Series 6, Vol. 2 (Scottish History Society, 2012), pp. 23–31.

Share this

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free