Punishment of sin by the Perth kirk session

There were several levels of punishment for sinners, depending on the seriousness and notoriety of the sin and the degree of penitence exhibited by the sinner.

The First Book of Discipline ruled that public sins had to be punished publicly, but for lesser offences and a sorrowful offender a private admonition by the session sufficed. This was often accompanied by a fine, always designated for the use of the poor – never, as in English archidiaconal or consistory courts, for the court personnel: Scots elders served without remuneration. The amount of the ‘pund’ or fine varied according to the seriousness of the offence and whether recidivism had occurred. Antenuptial fornication, for instance, had a standard penalty of 40s from at least 1577, the fine doubling each time the offence was repeated. In very rare cases, punishment by public humiliation or imprisonment could be commuted to a monetary penalty. Quarrelling could result in a fine; however, parishioners at odds with each other could instead be privately reconciled at a closed session meeting – as long as their quarrelling had not been public.

For more notorious sins and/or less penitent sinners, public humiliation in addition to a fine was in order. This was most often assignment to a specified number of appearances (on Sundays and other preaching days) on the seat of repentance, an elevated stool or bench to which the offender processed at the beginning of the service, and on which he stood to confess his sin following the sermon. Particularly egregious offenders were ordered to wear sackcloth and appear barefoot and bareheaded; sometimes they had to process through the streets to the kirk wearing a paper hat on which their offence was written. In extreme cases of sexual offence, the sinner’s head could be shaved for maximal humiliation; it should be noted, however, that this happened in Perth only during the plague year, when the elders sought desperately to allay divine wrath by exercising the sternest possible discipline of sinners.

There were less onerous forms of public repentance. People found guilty of slandering or notoriously quarrelling with their neighbours, for instance, could stand in their own pew or place in the church after the sermon and ask the forgiveness of the person they had offended; quarrellers were then assigned to take each other by the hand in token of their reconciliation. Often the elders ordered the ritual of reconciliation to be set in the place where the quarrel had occurred so that the neighbours scandalised by their behaviour could see it repented and corrected.

On the other hand, there were also more onerous penalties, entailing corporal punishment. Here the cooperation of the magistrates was required, since ecclesiastical courts after as before the Reformation were supposed not to have power over life or limb. Only the bailies could legally carry out corporal punishment. In practice, partly because of the personnel overlap between the magistracy and the session, the clerk frequently records that the session assigned recalcitrant offenders to ward (gaol), crosshead (two hours pilloried in irons at the market cross), dunking, carting (being paraded on a dung cart through the town), banishment, and even execution, confident that the bailies would comply. Warding was either in the kirk tower (for sexual offenders), in an upper chamber of the tolbooth, or in the Spey tower. That it was a dreadful experience is clear from complaints about the condition of the gaols, infested with vermin. That there were ways of making the ward a little less awful is suggested in the 20 November 1582 entry about sexual offenders going to the kirk tower’s window – to talk with their friends below, perhaps, or just to get a breath of fresh air. Only about twelve feet square, the ‘ward of the fornicators’ in St John’s kirk would have made cramped quarters, especially if divided into sections for men and women. People also stored timber in the tower, as we know from the session’s periodic efforts to make them remove it; some, however, would remain in the tower for erecting the town scaffold – a feature of the tower experience that may have gone a long way to inspire penitence in the sinners imprisoned there. The size of the Spey tower and tolbooth prisons is unknown, but conditions there were doubtless wretched as well, as suggested by desperate attempts to escape: in one instance, a man burned the wooden door of the tolbooth gaol to escape, only to have a neighbour raise the hue and cry. These conditions are worth remembering when reading of the elders’ frequent consignment of sinners to ward. A sentence to the crosshead was added to warding for the most audacious sinners, like Barbara Brown, who foolishly boasted of her acts of fornication while sitting on the stool of repentance in the church on a Sunday.

The most serious spiritual penalty was excommunication. What is striking from these minutes is how seldom it was threatened, let alone imposed. The elders ordered excommunication in only six cases during the fourteen-year period of this volume. They threatened to excommunicate recalcitrant offenders in an additional twenty-two cases. Their apparent reluctance to impose the sanction was perhaps rooted in part in the pre-Reformation church’s reputation for abusing it for self-interest and material profit – a complaint versified in 1540 by the Catholic reformer Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount in his oft-cited Ane Satyre of the Thre Estatis, where an impoverished parishioner vigorously denounces his parson: ‘The devil stick him, he curst me for my teind [tithe payments] And halds me yit under that same proces [excommunication] That gart me want the Sacrament at Pasche. [that made me lose my Easter communion]’. Lyndsay was probably not exaggerating very much: pre-Reformation ecclesiastical documents amply attest to Catholic abuse of the penalty. As a result, a General Provincial Council of 1552 had complained that excommunication ‘has in many places become almost of no account’. The earliest Scottish protestants adopted Lyndsay’s refrain, and their heirs must have seen the precedent as one to be avoided at all costs.

More importantly, the elders seem to have taken seriously the instructions in the First Book of Discipline, whose authors regarded excommunication as a last resort for only the most recalcitrant and impenitent offenders. They required the elders first to reason with sinners, persuade them of their errors, and ‘travail’ to elicit repentance and confession. The kirk must be diligent in this so that ‘it excommunicate not those whom God absolves’. Even ‘if the offender called before the ministry be found stubborn, hard-hearted, or in whom no sign of repentance appears, then must he be’ not excommunicated, but ‘demitted with an exhortation to consider the dangerous estate in which he stands’ and warned to repent. If this private admonition failed, ‘then must the [whole] kirk be advertised’ by an announcement from the pulpit, the congregation ‘earnestly to call to God to move and touch the heart of the offender’. If the sinner still remained impenitent, ‘request should be made to the most discrete and nearest friend of the offender to travail with him to bring him to knowledge of himself and of his dangerous estate, with a commandment given to all men to call to God for the conversion of the unpenitent’. The General Assembly even requested in 1569 that John Knox provide a special ‘Prayer for the Obstinate’ for the Sunday after a final (third) public admonition. Three public admonitions were mandated before excommunication could be pronounced. It was only at this point, absent signs of repentance, that the offender could ‘by the mouth of the minister and consent of the ministry [session] and commandment of the kirk … be pronounced excommunicate from God and from all society of the kirk’.

In practice, the process generally took even longer than the First Book required. Lengthy ‘travailing with’ offenders indicates that the elders were in no hurry to execute the sanction. In Perth, Elspeth Carver’s adultery conviction came nine months before her excommunication in January 1579. (Life for an excommunicate within the walls of the burgh proved intolerable for Carvor, who fled the town only to discover that life as a fugitive was even worse. She returned in July 1579, repented publicly and was restored to the congregation in an elaborate penitential ceremony.) Margaret Ruthven’s excommunication took even longer: it came thirteen months after her April 1578 adultery conviction. For the first six months, she seemed immune to the elders’ efforts to excite her penitence. Then in October, they seem to have made a breakthrough, for she then admitted her sin and claimed penitence. The elders (inveterate sticklers) were suspicious, however, since at the same time she requested baptism for her illegitimate child: the children of excommunicates were denied the sacraments, and this clearly troubled her.150 Doubting true penitence, the elders continued to ‘travail with’ her, only giving it up and pronouncing excommunication in May of 1579. That did the trick: just a week later, she appeared before the session ‘declaring that she is penitent as well of her adultery as of her obstinancy, for the which she has submitted herself with reverence and humility’. After a lengthy sentence of public repentance, she was restored to communion in September 1580. Repeated threats of excommunication and a year and three months of travailing with the adulterer John Scott convinced the elders that he was penitent for his April 1578 sin; unfortunately, Scott made a poor impression on the stool in July of 1579, so the order,‘speik John Scott’ continues to recur in the minutes as elders made heroic efforts to bring him to contrition so that he would ‘keep better order in time coming touching his repentance’. The last recorded of these visitations was in February 1581, nearly three years after the sin. In most cases where excommunication was pronounced, not only was the offender demonstrably – even audaciously – impenitent, the offence was also particularly egregious; even so, ‘long travailing’ ensued.

The language of the excommunications read out by ministers in the kirk demonstrate both adherence to the principle of the First Book and the rather bureaucratic bent of sessions – always careful to keep account of their actions. When the minister on 11 April 1585 pronounced Margaret Watson’s excommunication from the pulpit, he did so ‘with the grief, sorrow, and dolour of my heart’, even though Watson’s double adultery was aggravated by having produced two children, ‘which bairns received never the sacrament of baptism, and one of them she suffered to perish and starve for hunger in the lodges infected with the pest’ during the great plague outbreak of 1584–85, when victims were made to live in shacks outside the town walls. But it was ‘her stubborn disobedience to the voice of the kirk, after many due admonitions’ (which the minister duly enumerated and dated) that made excommunication unavoidable. The list that ensues, of elders, ministers, and the reader who admonished her at various times to repent and who formally witnessed the public admonitions ‘with the rest of the whole congregation in time of preaching and divine service’, together with Howieson’s formal subscription of the document, reminds us of the session’s legal and bureaucratic aspect. More important is the elders’ clear preference to avoid cutting a member off. Even after this excommunication, efforts to elicit repentance continued, and Watson was finally persuaded to repent in April of 1586.

Exclusion from communion had serious implications for the state of one’s immortal soul, of course; more immediately, however, the social meaning of the penalty was potentially devastating. The First Book of Discipline ordered that an excommunicate must be shunned by neighbours: ‘none could have any kind of conversation with him, be it in eating and drinking, buying and selling, yea in saluting or talking with him (except that it be at commandment or licence of the ministry for his conversion), that he by such means confounded, seeing himself abhorred of the godly and faithful, may have occasion to repent and so be saved.’ This language was echoed by parliament’s order that no one was to ‘receive, supply, or entertain’ an excommunicate. Exclusion from the spiritual community of the faithful was synonymous with social and economic ostracism. An excommunicated merchant lost his trade, a craftsman his clientele, a servant her employment and therefore her lodging.

The elders discovered, however, that enforcement was not easy in a culture that valued hospitality and loyalty to kin. Despite heavy fines or public humiliation for anyone caught ‘entertaining’ an excommunicate, neighbours, masters and clients regularly flouted excommunication orders and socialised with them, even offering them bed and board. In 1585 the session responded with an act that ‘no person society or company with excommunicates like Jean Thornton, the Master [Patrick] of Oliphant, or Margaret Watson under pain of censures of the kirk, and their entertainers to be warded and admonished under pain of excommunication to put them out of their company’, only to find that it would have to be renewed repeatedly. Kin who associated with excommunicates were exempted by a provision of the First Book of Discipline, which acknowledged the importance of family in Scottish society by providing that after the ‘sentence [of excommunication] may no person (his wife and family only excepted) have any kind of conversation with him …’. But no such caveat was allowed for either lesser or preceding forms of discipline. The elders actually imprisoned mothers for refusing to present their daughters, and demanded hefty fines of brothers for hiding their sisters from session prosecution. In 1582 Bessie Patty, after a month in gaol, finally admitted that she had been hiding her daughter from the elders’ discipline ‘in the stair (a sort of Harry Potter closet), albeit she said to the assembly that her daughter was in Balthyok’. Even after further admonition, she failed to turn her in and so was sent back to gaol for eight more weeks. In 1581 the session ordered ‘sundry householders in whose houses an vicious person is deprehended’ to pay fines of 13s 4d.

Things could be even worse for those who failed to repent, or whose offences were very serious. The worst of the lot could be banished from the community (the bailies’s authority again underpinning that of the session), or put to the horn (outlawed), or even executed. The elders sometimes ordered banishment even without excommunication – by implication, a declaration that they had no hope of bringing the offender to repentance and now washed their hands of him (or more often, her, since this most frequently happened to known harlots). This was the case when they summarily expelled Christen MacGregor from the town without spiritual sanction ‘in respect of the great abuse of her body’. Horning meant that no one, including kin, could feed or shelter the offender; indeed, one ‘put to the horn’ could be captured on sight and brought to the local magistrate for execution, since by statute law (as the horning proclamation for adulterers iterated) ‘all notorious and manifest committers of adultery shall be punished with all rigour unto the death, as well the man as the woman’, and their goods escheat to the crown.

The execution of sinners was a rarity, occurring during our period in Perth only once. In January of 1585, Helen Watson and David Gray, both married, were caught in David’s bedchamber with Helen in a state of partial undress by the town watchmen, who brought them to the session. The elders questioned both offenders and witnesses, discovered that their relationship had been going on for some time, and then took the unusual course of turning the couple over to the bailies for inquest. Very shortly thereafter, the unfortunate lovers were hanged on a gibbet erected before Watson’s mother’s front gate — the sole instance in this burgh of adulterers being executed, though death was prescribed by parliamentary statute for notorious adultery. But context matters: since the fall of 1584, the black death and a concomitant famine had been raging in Perth. The session made quite clear its presumption of the close relationship between plague and adultery in its ‘supplication … unto the bailies’ for an inquest: they sought ‘justice according to God’s law and the laws of this country lest that otherwise being long winking at their wickedness, God of his justice plague both us and you with the rest of this city as miserable experience has begun to teach us’. The record does not indicate whether Watson and Gray were penitent, or whether anybody cared. In the midst of a natural disaster understood as divine judgement for the toleration of sin, the need of the community to identify and eliminate the source of plague overcame the commitment of the kirk to securing repentance, amendment of life, and re-integration of sinners into the community of the faithful. It is no accident that the only reports we have of shaving and ducking fornicators also occur in this plague season. Reformed discipline amidst the crisis of epidemic disease gave way to sheer terror and primitive recourse to scapegoats.

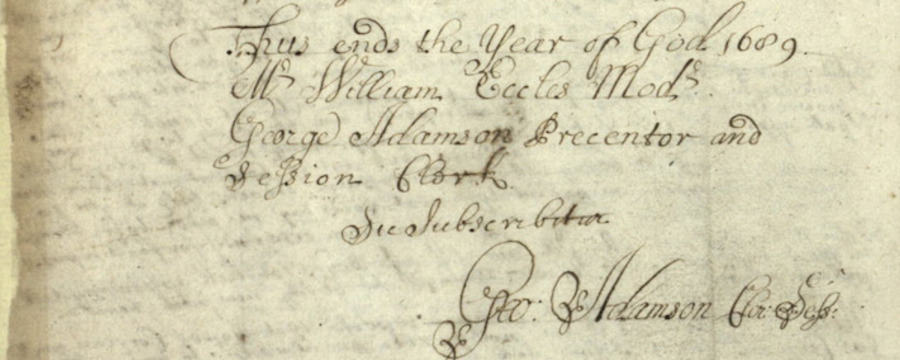

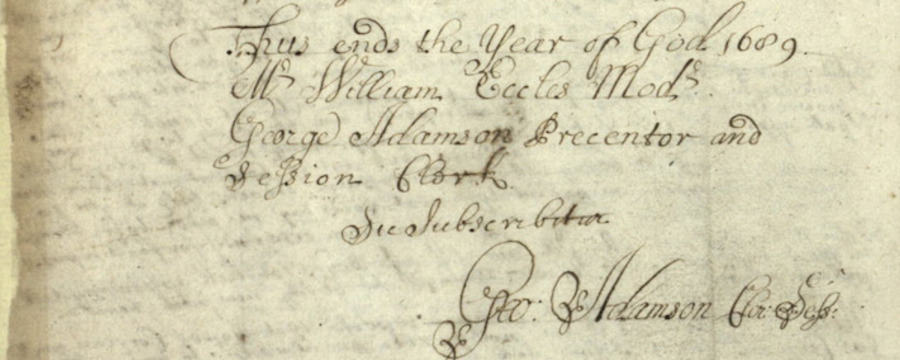

Excerpt from Margo Todd (ed.), The Perth Kirk Session Books 1577–1590. Series six, vol. 2 (Scottish History Society, 2012), pp. 36–45.

Share this

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free