Perth kirk and its records: burgh and people

Share this step

Perth in the sixteenth century was a town of between five and six thousand people.

Positioned at the highest point of the River Tay then navigable by seagoing vessels, its flourishing economy was based on trade across the North Sea as well as with its hinterland, and on a wide range of crafts produced for this market. The Tay, a tidal river, is fordable a few miles above Perth so that the town was strategically placed on a north-south trade route with the interior, but it was deep enough at Perth for high tide to carry ships to the sea. Walled on three sides (though the wall was by the sixteenth century in disrepair), the town’s fourth side was defined by the river, with a new harbour and wharves constructed in 1539 at its southeastern corner. (See Map.) This replaced a more northerly one (at the east end of the Highgait) whose utility had been undermined by silting and by crowding of the wharves due to urban expansion and the increasing volume of shipping. Just north and south of the town are two ‘inches’ – meadows where sixteenth-century boys were often caught by the elders playing golf during service time.

The street (gait) layout in the old town has changed little since the Middle Ages. The Highgait (sometimes called North Street, now the HighStreet) runs east-west parallel to the Southgait, joined at the east end by the Watergait and the west by the Meal Vennel. The result is a natural procession route, allowing complete perambulation of the town within the walls from the market cross in the Highgait or the kirk just south of it or the tolbooth at the east end of the Highgait – symbolic centres of economic, religious, and political life in the burgh. The importance of such processions even after the Reformation will be apparent in the kirk session minutes. Elders would be elected to the session from each of the ‘quarters’ of the town, defined as the north and south sides of the Highgait, the Watergait or east end of the town, and the Southgait. In the town’s walls were four ‘ports’ or gates, which were locked at night, during plague seasons, and (after the Reformation) during the Sunday sermons — with the porter’s occasional lapses sternly reprimanded by the session.

Outside the walls and positioned roughly at the four corners of the pre-Reformation town were the most important religious houses – Greyfriars (Franciscans, at the southeast corner), Carthusians (at the southwest corner), Whitefriars (Carmehtes, further afield northwest of the town at Tullilum), and Blackfriars (Dominicans, north of the walls toward the eastern end of the town). The ruins of a castle destroyed by a flood in 1209 lay within the site of the Dominican house in the northeast, so that ‘Castlegavel’ names the vicinity and the street leading to it. There was in addition a plethora of medieval chapels in and near the burgh, oft-mentioned in the session minutes, either because their buildings survived and continued in use or because their vast properties had become the financial basis for post-Reformation poor relief. Several of the chapels had attached hospitals, at least two of which would survive the Reformation and continue in use for a time, as the kirk session minutes show. St Ann’s, St Paul’s, St Catherine’s, St Leonard’s, and St Mary Magdalen’s all had hospitals devoted to the poor and infirm. The first two, located near the kirk and just beyond the Turret Bridge port, respectively, continued to serve as hospitals into the 1580s. St Mary at the Bridge also survived and was transformed in 1596 into a ‘hospital house for the entertainment of the poor’, though only after an expensive restoration ordered by the kirk session. Other chapels, including Loretto, St Lawrence, and Holy Rood, fared less well at the Reformation. Readers of the session minutes will notice that the tides ‘prior’ and ‘curate’ continued in use in the 1570s and 1580s for the lay holders of former monastic properties as well as former Catholic clerics who had been pensioned off at the Reformation. Such men as ‘the Prior of Quhyteffiars’ and ‘Sir Alexander Cok, curate’ (listed on a 1584 poor roll) no longer held ecclesiastical office, but they did collect stipends for their lifetimes as a matter of protestant charity to men with careers in the old religion.

A fifteenth-century suburb at the west end of the town was defined by a street of houses and shops called ‘New Row’, and there were also populous suburbs to the north of the walls, where mills were powered by a lade constructed in the twelfth century to bring water from the River Almond at Huntingtower Haugh. Fullers (waulkers) and tanners, dependent on a good water supply, joined the millers here. A canal along the southern boundary of the town served as a tailrace from the town mills.

The bridge across the Tay at the end of the Highgait was essential to the town’s economy, connecting it to the Dundee Road and other important trade routes. An arched stone construction, it required frequent repair because of repeated damage by storms and floods. The town council in 1586 noted that the bridge had recendy fallen twice (in 1573 and 1583), and that the most recent timber repair was again ‘ready to fall without present help’. At the burgh’s behest, parliament in 1578 granted a tax of 10,000 merks for repairs, but the Privy Council in 1585 noted the bridge ‘twice fallen and much decayed’. By the 1590s, a new bridge was being constructed, but it, too, had fallen by 1601. The next bridge was completed in 1617 but was ‘utterly overthrown’ by the great flood of 1621. The session would read the condition of the bridge as a sort of barometer of divine approval or punishment: a flood that damaged the bridge was a warning that God frowned on the behaviour of the citizenry, or on the community’s tolerance of sin, and one that destroyed it altogether was a clear and dire judgement. Divine anger was also read in the occasional earthquakes that rocked the town. Geologically, Perth is sited within Scotland’s Midland Valley, not far south of the Highland Boundary Fault, and it would in July of 1597 be severely damaged by an earthquake. The townspeople’s vulnerability to natural disasters is an important part of the background against which the new protestant church court conducted its business. A fundamentally providentialist view of the universe dictated that during times of presumed judgement, the proper response of the kirk should be seasons of fasting and humiliation for sin, together with even sterner moral discipline by its courts, lest God’s wrath impose more drastic punishment. The minutes of the session thus need to be read with both meteorology and the material structures of the town clearly in mind.

The two most important buildings in the sixteenth-century town were the tolbooth, where the council and bailies court met and criminals were gaoled, and the Kirk of St John the Baptist, whose revestry was the site of session meetings. The early modern tolbooth, site of the tron for weighing commercial goods, was also the occasional gathering place of Scottish parliaments, right through the seventeenth century, and public announcements were made from its window. It was not a particularly secure gaol, as reports to the bailies of successful escapes attest, and by the early seventeenth century it was in such disrepair that the 1606 Parliament had to move to a building off the High Street. The tolbooth was razed in the nineteenth century.

The kirk occupied an open space between High and South streets, surrounded by its graveyard, with the Kirkgait joining it to the Highgait. St John’s is a fine fifteenth-century hall church, re-constructed at great cost on the site of the earlier medieval church between 1440 and 1511, its steeple filled with expensive Flemish bells newly cast in the early sixteenth century. On the eve of the Reformation, it boasted at least forty side altars devoted to an array of saints. These were lavishly decorated and lit by their lay patrons, both individuals and guilds. Indeed, the sums of money spent by late medieval burgesses on the parish church, together with impressive additional expenditures designated to endow masses for the souls of the dead in the plethora of chapels both in the burgh and just outwith its walls, suggest that Catholic devotion and the doctrine of purgatory in the generations immediately before the Reformation were by no means unpopular.

Ecclesiastical structures and the tolbooth would have been among relatively few stone buildings in the sixteenth-century town, though there was considerable new stone construction in the early seventeenth century. Kirk, tolbooth, the grand townhouses of local lords and lairds, and the wealthier burgess’s dwellings were exceptions to the rule of building mostly in timber and wattle. There were in the sixteenth century no guild halls: most guildsmen held their meeting outdoors, either in the South Inch, a meadow outside the walls and along the river, or in one of the burial grounds.

Ordinary dwellings were constructed on the long, narrow tofts extending out from the main streets. Originally intended for a narrow-fronted dwelling on the street and space behind for gardens, small livestock, and outbuildings, by the later sixteenth century these were heavily built for habitation on the ‘backlands’ as well as the frontage. The density of early modern Perth’s population — with nearly twice the population packed into the small area within the walls as lives there now in that space — ought to be borne firmly in mind when reading the session minutes’ reports of neighbours spying on each other, catching each other out in sins, and observing public quarrels and ritual repentance on the streets where offences had occurred. An early modern town was not a setting where privacy was either desirable (at least by the well-behaved) or possible.

The town’s population was more culturally diverse than one might expect. Numerous Gaelic names appear among the majority Scots and occasional English ones, not just among the burgesses and tradesmen, but also in lists of office-holders in guilds, council, and session. Perth served as a gateway to the Highlands. Its merchants did business with Gaelic traders and timber-sellers, its leather-workers dealt regularly with Highland cattledrovers, and its cutlers made Highland-style swords; there was also a lively market for Highlandmen’s tartan cloth. Perth burgesses served as bankers for itinerant Gaels, at least offering safekeeping for their coin. Prominent Perth burgesses served as cautions for ‘Highlandmen’ in business dealings. It should not be surprising that some Gaelic families were long-settled in the town. As the kirk session minutes demonstrate, intermarriage (and less legitimate relationships) between people with Scots and Gaelic surnames was frequent, both within and beyond the walls. The session records thus provide a window on contemporary notions of insider and outsider, of who did and did not properly belong to the parish. This would prove to be defined not by the Gaelic/Scots distinction – not a significant divide in this parish, but rather by quite different factors. ‘Entertaining strangers’ – offering bed and board to travellers without proper documentation – was a rigorously punishable offence here as in most early modern communities. But Perth’s magistrates and session imposed the strictures of the law when those ‘entertained’ were excommunicates or others under ecclesiastical discipline, unauthorised beggars, or ‘Egyptians’ (gypsies). Highlandmen or ‘Irish’ – the usual names for Gaelic-speakers – were not per se problematic. They were too essential to the town’s economy.

Perth’s prosperity depended on both its manufacture and its mercantile endeavours. Its merchants engaged in both domestic and overseas trade, the latter mainly with Flanders, Denmark, and England. Exports included tar and pitch, skins and leather goods, wool and cloth, butter, and salmon. Wine and fine cloth were imported in large quantities. For domestic exchange there were four annual fairs, at Midsummer, St John’s in Harvest, Andersmas, and Palm Sunday, in addition to regular weekday markets. There were nine incorporated trades, or craft guilds, in the burgh – the hammermen (smiths working in gold, silver, iron, brass and pewter, together with saddlers, armourers and gunsmiths), baxters (bakers), tailors, skinners and glovers, cordiners (shoemakers), fleshers (butchers), wrights (including makers of carts and wheels, coopers, masons, and joiners), wobsters (weavers), and waulkers (fullers, including bonnetmakers and hatmakers). Their relative importance can be gauged by the assize of nets or fishings in the Tay, with one each held by the hammermen, skinners, glovers and baxters and the lesser trades sharing two. It will be unsurprising that of the thirty-four craftsmen among the elders of 1576–90, twenty-five were from the hammermen, skinners, or baxters.60 The other important guild in the town, the mercantile guildry, held six nets, reflecting its greater wealth and status. It is important to remember, however, that many craftsmen were also members of the merchants’ guild. In fact, nearly all of Perth’s elders were members of the mercantile guildry, but only thirty-four have ‘merchant’ attached to their names in records that indicate occupation.

The freemen of each craft guild selected their deacon and other officers, including a boxmaster who was in charge of the money collected in dues, fines, and rents on properties held by the corporation. (Deacons of crafts should not be confused with deacons in the Reformed church, who were elected to attend to monetary collections, poor relief and other material aspects of the kirk’s business.) Each craft deacon also served as his guild’s representative on the town council. Guild masters elected their own councils and other officers. The hammermen, for instance, chose annually ‘eight masters’ as a council along with two compositors or treasurers, an ‘officer’, and ‘visitors’ or inspectors of the markets. Guild officials patrolled the markets as well as craftsmen’s shops or ‘booths’ (generally located at the front doors of their houses), enforced standards of production, and joined the council in fixing prices. Opening and closing hours were strictly regulated and enforced by the guild masters and magistrates, and since long before the Reformation, guilds prohibited sabbath trade. They also traditionally disciplined their own members, their fials or ‘servants’ (‘journeymen’ in English parlance), and their apprentices. Occasional settlement of quarrels within a craft by the kirk session rather than the deacon of craft may be taken to indicate the session’s relative power and effectiveness as an arbiter in this period; on the other hand, it may simply reflect the number of craftsmen on the session inchned to use guild procedures in the new ecclesiastical court. It is worth bearing in mind when examining kirk session minutes that the elders were virtually without exception members of either the mercantile guildry or crafts guilds (often both); they accordingly came to the church court already experienced in self-government, the ‘nitty-gritty’ of administration, the provision of aid to guild dependents (widows and orphans of deceased brethren, for instance) and the execution of discipline on their own members. They were well-equipped to do the work of the new protestant kirk.

Perth is justly known as a ‘crafts town’ relative to towns like Aberdeen and Edinburgh, where merchants completely dominated politics. This had been the case in Perth at the beginning of the sixteenth century, but with the crafts guilds paying half of the town’s royal taxes, the craftsmen had managed steadily to increase their political clout. From 1534 they supplied at least two members of the council, and from 1544 they provided one bailie. They were determined to keep improving their political lot, however. A disputed election in 1556 ignited a craftsmen’s riot, and in 1560 crafts deacons began attending council meetings without invitation. Only in 1572, after decades of jockeying for political power, did the crafts finally get equal council representation with the merchants — at least in theory; in fact, there were more often four than six crafts councillors in the 1570s. But crafts deacons now attended council meetings by invitation, and from 1572 the town treasurer every other year was a craftsman. A modus vivendi had clearly been worked out to reduce the tension between the two groups that had been such a constant feature of the previous half-century. It doubtless helped that by mid-century the membership of the mercantile guildry was drawn heavily from craftsmen. In this town the crafts were clearly a force that could not be ignored. As we shall see, a balance between the two groups became visible in the composition of the kirk sessions – a natural outworking of burgh politics.

Like most early modern European towns, Perth was governed by a self-perpetuating oligarchy; only the loud political voice of its craftsmen set it apart from the political norm in Scotland. A council of twelve leading burgesses chose its own successors every Michaelmas. The old and new council, sitting together with the deacons of the incorporated crafts, then elected four bailies and a provost. The latter was a powerful local lord, in our period William, fourth Lord Ruthven, heritable sheriff of Perth, who would in 1581 become the first Earl of Gowrie. Ruthven served until his execution for treason in 1584; he was succeeded by John Earl of Montrose, then John Duke of Atholl in 1585 and 1586, the merchant (and elder) James Hepburn in the fall 1587 election, and by the end of that year the second Earl of Gowrie. On extremely rare occasions, the provost sat with the kirk session. More usually he had nothing directly to do with the session’s business, though the presence in or near town of a powerful aristocratic patron of Calvinist and presbyterian protestantism may have helped to spur the rapid establishment of session government in the burgh. The bailies, on the other hand, were essential to the session s day-to-day operations. It was they who saw to it that prescribed corporal punishment was carried out. Quite apart from overlapping personnel, the session and the council worked in tandem.

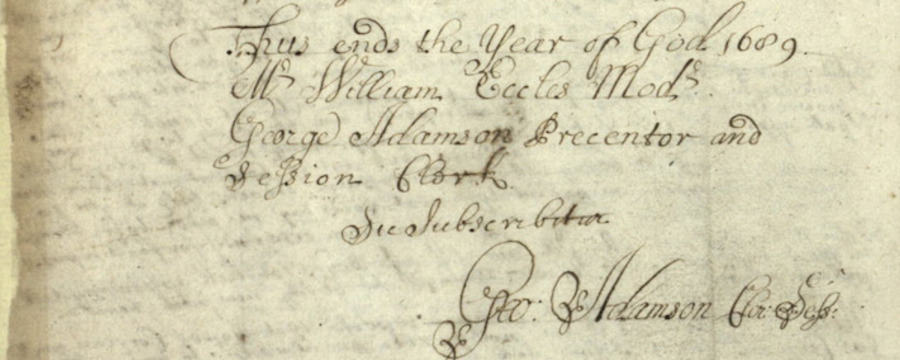

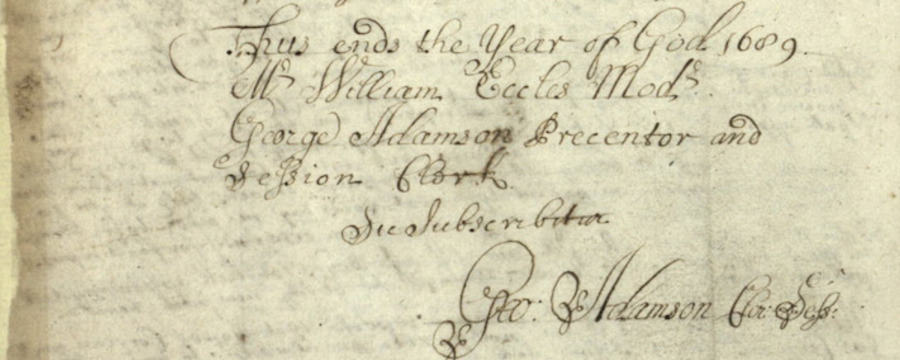

Extract taken from Margo Todd (ed), The Perth Kirk Session Records, Sixth Series, Vol. 2 (Scottish History Society, 2012), pp. 9-19.

Share this

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free