Genes for Alzheimer’s disease explained

This article gives an overview of the genes responsible for familial Alzheimer’s disease, and describes some of the more common genetic risk factors that influence the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Inheriting familial Alzheimer’s disease

As we’ve heard, people with familial Alzheimer’s disease have a change (known as a mutation) in one of three genes; APP, PSEN-1 or PSEN-2. Familial Alzheimer’s disease is also sometimes called autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. We inherit two sets of 23 chromosomes, one set from the mother, the other from the father. There are 22 numbered chromosomes, and the X and Y chromosomes. Autosomal means that the gene is found on one of the numbered chromosomes (not the X or Y sex chromosomes), and dominant means that if you have one gene with a mutation you will show the effect of having that gene (despite receiving one gene without the mutation from the other parent). The result of this is that if one of your parents has the gene, you have a 50/50 chance of receiving the gene, and if you receive the gene you will unfortunately develop Alzheimer’s disease. People with these genes tend to develop Alzheimer’s disease in their 30s or 40s, and the condition is very rare, thought to represent less than 1% of all Alzheimer’s disease cases1.

Why do changes to these genes cause Alzheimer’s disease?

The three familial Alzheimer’s disease genes have a common effect, they all change the way that a protein called amyloid is formed in the brain. This change contributes to developing amyloid plaques – sticky build-ups of certain forms of the amyloid protein which are a hallmark feature of Alzheimer’s disease. The discovery that familial Alzheimer’s disease is caused by genes that result in amyloid plaque formation was an important piece of evidence that led to the suggestion that removing these amyloid plaques could slow or even stop Alzheimer’s disease from developing. This idea is being tested now in clinical trials that remove amyloid from the brain, and you’ll learn more about that later this week.

What about other genes that increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease?

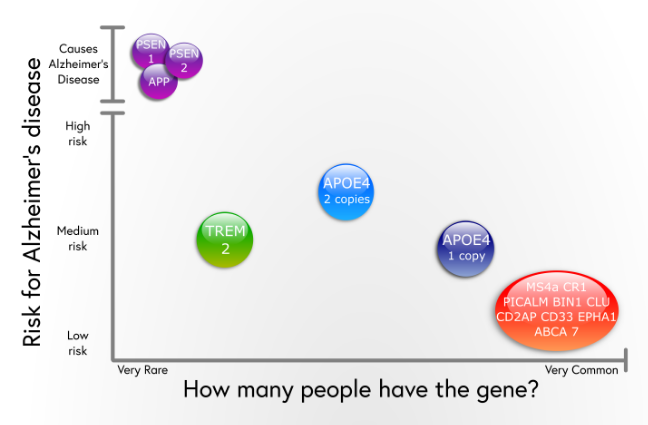

The diagram below shows a number of genes associated with Alzheimer’s disease according to how common they are. Mutations in the APP, PSEN-1 and PSEN-2 genes are rare, but having a mutation gives a very high risk (or even certainty) of developing Alzheimer’s disease, so these genes are shown in the top left of the diagram.

Most people who develop Alzheimer’s don’t have familial Alzheimer’s disease, the particular reason that they develop the disease isn’t clear. It’s most likely to be due to a combination of factors such as age, environment, lifestyle and genetic risk factors. In these cases, the disease is known as ‘sporadic’ – there isn’t one clear cause. Some of the ‘risk factor’ genes are shown in the diagram above. Having one of these genes means you’re more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than someone who doesn’t have the gene, but it doesn’t mean you’ll definitely develop Alzheimer’s. These genes increase your risk slightly, but some people with the genes don’t get the disease, and vice versa. There are a number of genes that are very common – lots of people have the form of the gene that increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, but they don’t have a strong effect. These are shown in the bottom right of the diagram (e.g. CR1, BIN1, ABCA7). TREM2 on the other hand is fairly rare, but has a greater effect than those more common genes2.

How much do these risk factors change the risk?

Let’s take the example of APOE. APOE is a gene that comes in a number of different variants (known as alleles), APOE e2, APOE e3 and APOE e4, and you receive one allele from each parent. If you have one APOE e4 allele, you have a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. If you have two APOE e4 alleles (one from each parent) your risk is even higher, but it’s still not a certainty, this is reflected in their position in the diagram above. It might help to understand this in simple numbers.

According to one study3 if we take 100 men aged 85, we would expect 10 to develop AD during their lifetime. The figure for women is slightly higher, 14 out of 100. However, if we take a group of 100 men who have one APOE e4 allele and one APOE e3 allele we would expect 23 of them to develop AD. Again it’s slightly higher for women, at 30 out of 100. The numbers are even higher for people who have two copies of the APOE e4 allele (51/100 for men and 60/100 for women), but having these genes still doesn’t completely determine whether you develop Alzheimer’s disease or not. Having two APOE e4 alleles isn’t all that common, between 10% and 30% of the population may have this particular genotype4,5. The other variants of APOE (APOE e2 and APOE e3) don’t increase your risk, in fact studies suggest the APOE e2 allele is slightly protective.

Is it genetic?

‘Is it genetic?’ is a common question asked by people who have dementia, or people who have family members or relatives with dementia. The answer is in most cases it isn’t caused by a single gene, but some genes increase your risk of developing dementia, as do other things such as age and lifestyle factors. Because dementia is very common, lots of people may have a number of family members with dementia. It’s when there are a number of people in a family who develop Alzheimer’s disease quite young (before 65) that a doctor may consider suggesting a test for the familial Alzheimer’s disease genes.

Can you be tested to see if you carry a gene that causes Alzheimer’s disease?

This is another very common question. It is possible to detect whether people are carrying a mutation in one of the autosomal dominantly inherited genes, APP, PSEN-1 or PSEN-2, through a blood test. As explained above, it is extremely rare to carry one of these mutations, but if you do carry one, then you will almost certainly develop Alzheimer’s disease at a young age, and there is a 50% chance that you will pass on the faulty gene to any children you have. If someone shows symptoms at a young age, and there is a strong family history of young-onset Alzheimer’s disease or someone else in the family is known to carry a faulty gene, then this person can have symptomatic genetic testing to confirm the presence of the gene. If someone doesn’t have symptoms but it is known that one of their parents carried a faulty gene, this person could opt to go through genetic counselling and after that they may decide to have presymptomatic testing to see whether or not they carry the gene (even though they aren’t showing any signs of Alzheimer’s disease yet). This is a very tricky decision: some people prefer not to find out and to live with the hope that they don’t have the gene; others feel that they are better able to plan for the future if they know.

What is your interpretation of the genetics of Alzheimer’s disease, and the risk of developing it? Risk is something that people interpret in different ways, are the kinds of differences in risk described in this article meaningful to you?

Written by Tim Shakespeare

References

- Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a review and proposal for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease.

- TREM2 Variants in Alzheimer’s Disease

- APOE and Alzheimer disease: a major gene with semi-dominant inheritance.

- Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease.

- Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease.

Other sources

Alzheimer’s Society information on genetics of dementia

Diagram above adapted from image by Alzheimer’s Research UK in this article

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free