International Relations: Military Intervention

Share this step

It’s always tempting to intervene as soon as the opportunity presents itself. But, unlike in previous decades, when intervening meant waging war, it is now a question of preserving or of restoring peace.

When we no longer act through realism but humanitarianism, the opportunity (or obligation) to intervene rises dangerously. Besides, intervening whenever it is “necessary” in terms of global policing, overstretches the lines, and poses formidable logistics and reserve staffing problems, leading to a breaking point, when services can no longer be provided.

Not to mention the hatred that builds up in the invaded countries, hence a source of subsequent terrorist acts; Plus the risk the conflict will flare up again later, once the intervention or occupation schemes withdraw; Without any guarantee that the objectives of each intervention will be achieved.

The notion of a “Theatre of Operation”

In strategic terms, this is an independent war zone under a single command, where civilian and military actors, administrators and soldiers operate together. Theatre of operation sometimes means “front” or “battlefield”, or simply a “zone of military intervention”. Whenever it involves clearing up a situation affected by internal unrest. Clausewitz expressed the traditional view of the theatre of war in his famous book entitled “On War”.

According to him, this notion properly delineates “a portion of the space over which war prevails, (…) changes which take place at other points in the seat of war have only an indirect and no direct influence upon it. To give an adequate idea of this, we may suppose that on this portion an advance is made, whilst in another quarter a retreat is taking place, or that upon the one an army is acting defensively, whilst an offensive is being carried on upon the other.”

Recently, this concept has been extended to police and interposition zones. This shifting definition weakens its meaning: there are now “hard” and “soft” interventions in which the problems are obviously not the same. In a conflict situation, the interests of the intervening nation are defended. This is qualified as a ‘hard’ theatre of operation. In a humanitarian emergency, another nation’s lives are defended on a ‘soft’ theatre of operation. The concept is further weakened when the operation is conducted on behalf of other nations, for example, the United Nations.

Indeed, there are even greater constraints on-field operations: the rules of engagement are much more restrictive, even in the case of “self-defence”; Tact, reserve and self-restraint are also required; It might be necessary to take over from failing public services, to exercise police and judicial power within a local legal framework that is often too restrictive. As the concept and its use has been extended, the number of theatres of operation has multiplied (both hard and soft, which often slip from one to the other)

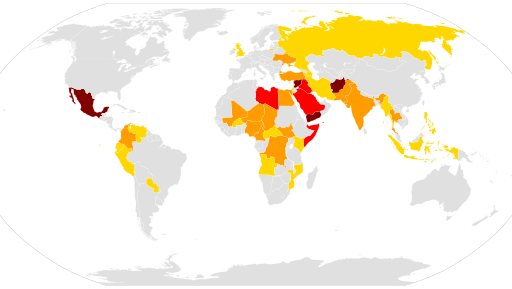

Map: Ongoing conflicts around the world, used under CC licence.

Map: Ongoing conflicts around the world, used under CC licence.

Here is a tentative list: The Balkans (Bosnia, Kosovo) The Caucasus (Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Georgia) The Middle East (Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon) Central Africa (Congo, Zaire, Mali, Central African Republic, Angola, Mozambique, Liberia, Sudan) The Horn of Africa (Somalia) The South China Sea (between North Korea and its neighbours, but also China, Japan, Taiwan).

Classic interventions

Classic interventions combine several sorts of military force, applying a ready-made protocol (operating by the book), including massive or surgical bombing, intervention on the ground, and temporary occupation of the territory.

This is exactly what happened in the Balkans in the nineties, although some questions about these wars remain unanswered twenty to thirty years later: which were necessary (Bosnia and Kosovo, perhaps?) or might be in the future (will Albania / Moldavia / and Transnistria become hot spots for European and Russian armies?).  Balkans map in the nineties, used under CC licence.

Balkans map in the nineties, used under CC licence.

The Caucasus case is even more troubled, and charged with emotion: nothing has been solved there (as shown by this map whose shaded areas are contested and whose grey areas are populated by populations who disagree with the powers in place).  Map: Geopolitical map of the Caucasus region, used under CC licence.

Map: Geopolitical map of the Caucasus region, used under CC licence.

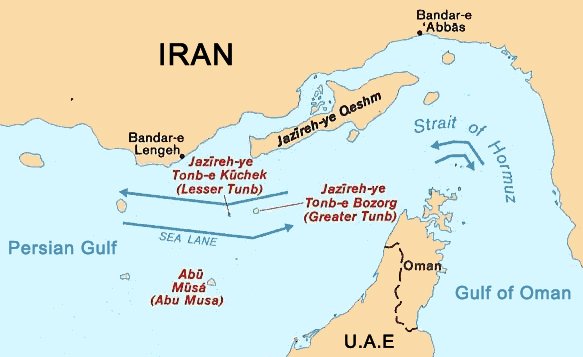

As for the Middle East, in the Strait of Hormuz, contradictory territorial claims make the region highly unstable (not to mention the case of Israel and its Arab neighbours).  Map: Strait of Hormuz, used under CC licence.

Map: Strait of Hormuz, used under CC licence.

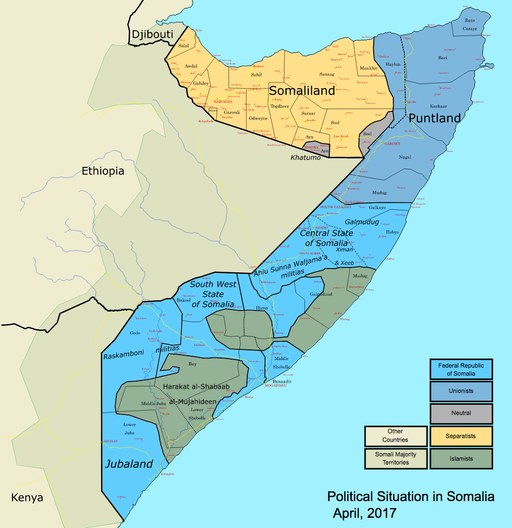

The Horn of Africa is also a source of trouble for near and distant countries, if only through a high risk of piracy. It is also an unstable zone in itself, with several self-governing regions).

Map: This map shows the states, regions, and districts of Somalia, as well as the current situation in Somalia , used under CC licence.

Map: This map shows the states, regions, and districts of Somalia, as well as the current situation in Somalia , used under CC licence.

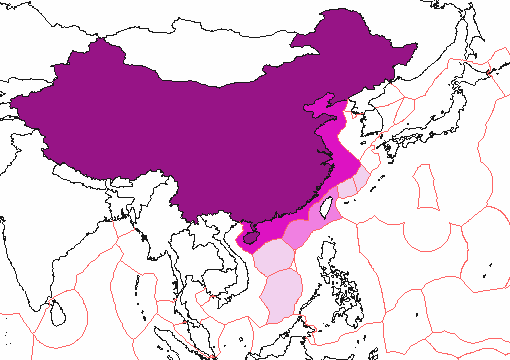

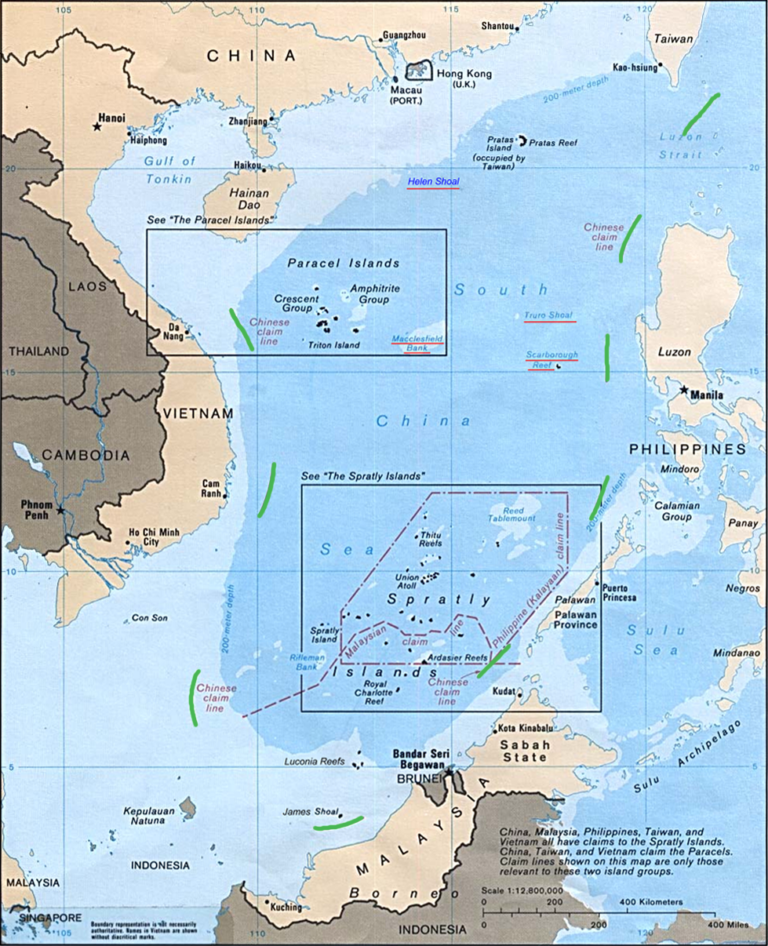

Finally, the South China Sea is an area where potential conflicts are on the rise, as shown by the dramatic extension of offshore Exclusive Economic Zones.  Map: the South China Sea, used under CC licence.

Map: the South China Sea, used under CC licence.

Map: the South China Sea, 1988, used under CC licence. These disputed territories are the setting for warlike episodes with live firing of ammunition, between the two Koreas, for instance, and several others.

Map: the South China Sea, 1988, used under CC licence. These disputed territories are the setting for warlike episodes with live firing of ammunition, between the two Koreas, for instance, and several others.

Humanitarian Interventions

Contrary to classic interventions, Humanitarian Interventions have less “selfish” goals (a state does better if the others are doing badly) than altruistic “milieu goals” – to quote Arnold Wolfers, a late American professor who claimed that a country would do better if the others were doing well). In more up to date vocabulary, states play more cooperative games than zero-sum games (which the ancient Greeks called “agonistic”, i.e. a test of power in a competition to win).

Humanitarian interventions have historic precedents, like the French intervention in Lebanon in 1860 to separate the Maronites and the Druze. In such contexts, the troops are welcomed as saviours.  The French intervention in Lebanon in 1860, Beaucé, Public domain.

The French intervention in Lebanon in 1860, Beaucé, Public domain.

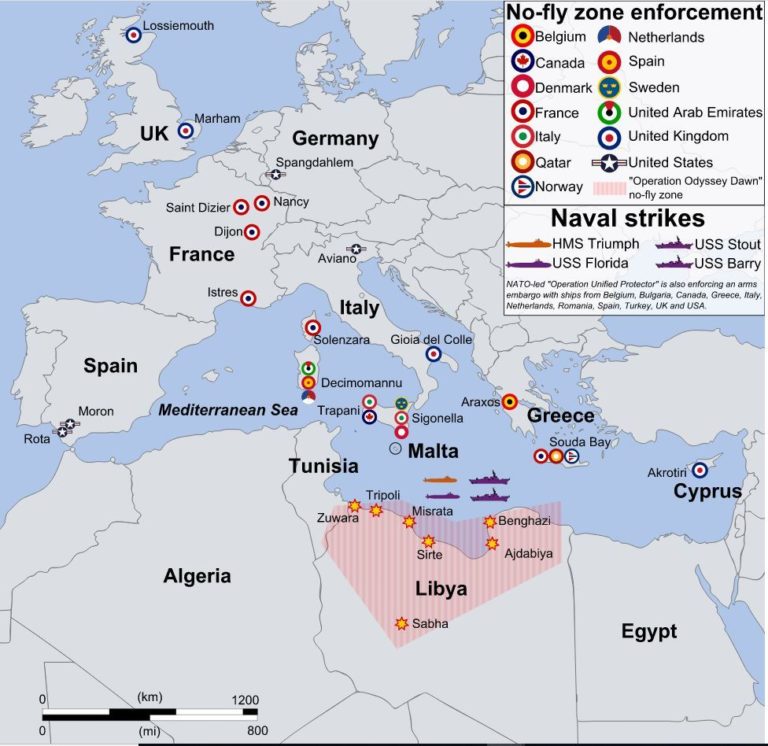

In recent emblematic cases (Libya, Syria, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, and the Central African Republic), it seems that history is repeating itself. In Ivory Coast apparently the coalition was effective. It enabled the country to move on from being split in two to becoming a controlled, though fragmented land.  A map showing events of the coalition intervention in Libya, used under CC licence.

A map showing events of the coalition intervention in Libya, used under CC licence.

In Libya, France and the UK separated the inhabitants of Cyrenaica from those of Tripolitania, on behalf of an international coalition. By contrast, in another Arab country, Syria, a Western coalition fizzled out despite extensive preliminary discussions. Later on, a Russian-Turkish-Iranian coalition rescued governmental troops, instead of separating them from their opponents.  International conference on Syria, in Cairo, 2012, Tunisian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, used under CC licence.

International conference on Syria, in Cairo, 2012, Tunisian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, used under CC licence.

Questions on military operations

Some military operations are “softer” than others, for instance when an interposition force or a police corps are sent to a foreign land. How effective are they compared to “harder” ones? Why intervene militarily in some places and not in others? What leads to success or failure? Will intervention automatically lead to lasting peace? How do the local populations respond to such “assistance”?

As authors point out, it is difficult for foreign chief of staff to decide between soft and hard intervention. Hard power avoids getting drawn into a quagmire, but the number of victims may be high. Soft power may entail abuse, like rape or torture, because of the longer time-span of contact with civilians.

Although spectacular action like the killing in Baghdad of an Iranian General in January 2020 may have been triggered by good intentions, it will inevitably trigger misunderstanding in the very people it is supposed to help. Officials and the people of Afghanistan, Iraq and the Sahel countries, which are among the most affected by bloody attacks, increasingly protest against the “occupation” of their land by foreign armies.

However, even the toughest operations facilitate the emergence of a new form of cooperation. In exchange for extended responsibilities, the few states able to intervene benefit from a general tendency to coordinate in conflict and post-conflict zones. Therefore, and counter-intuitively, the more theatres of the war there are, the more cooperation takes place.

Cooperation involves various partners: First, the armed forces on the ground (NATO forces in the Middle East, African armies with the French army in Central Africa; Ethiopian, Kenyan and African Union armies in Somalia; the US Navy, Korean Army and Japanese Self-Defense Forces in the South China Sea); Second, these armies and local governments or what remains of them; Finally, the armed forces and IGOs and NGOs in the field (Western and non-Western: for example, Turkish, Iranian, or those linked to the Islamic Cooperation Organization in Somalia or Syria). A fine example of cooperation is the fight against piracy off the coast of Somalia and Yemen.  Official logo Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA), used under CC licence.

Official logo Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA), used under CC licence.

However, in some cases, cooperation is either more difficult to set up, or riskier. Take the African Union’s rapid response force. Conceived as the equivalent in Africa of NATO for East European and Middle Eastern theatres of operation, its creation was promised in May 2013 at the Addis Ababa summit. It was announced again in November of the same year by the South African president at a meeting in Pretoria of states willing to contribute to the force (Chad, Niger, Senegal, Algeria, Ghana and Ethiopia). But it became partly operational in 2017 only.

The G5 Sahel, a French initiative to fight Islamic radical movements (like Al Qaeda In the Maghreb or Boko Haram) that are active in the barren areas between the Northern and Tropical regions of the continent, was set up in February 2014 in Nouakchott by the governments of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger.  Logo of the G5 Sahel force, 9 April 2019, used under CC licence.

Logo of the G5 Sahel force, 9 April 2019, used under CC licence.

Still in the offing despite 2018-9 renewed calls from the French head of state to relieve Barkhane troops on the grounds, its contribution to the removal of terrorism has been so far inconclusive. There are still scores of casualties.

New playgrounds

In addition to their traditional branches (army, marine, air force, special operations, etc.), technologically advanced states now have a Space Command and a Cyber Command. At the age of hypersonic guided missiles (a successful trial has been claimed by the Russian rulers early 2020) and military orbital satellites (with which the American and the Chinese have allegedly made tremendous progress), interventions involve higher risks – but greater gains for the victorious: the army which launches the first strike.

Some innovations may nonetheless spare lives on the ground, at least for the first mover – take for example the selective elimination of adversaries by military drones (the USA), radioactive substances (Russia), special forces (France), abduction in foreign territory (Israel), the freezing of their assets as well as the blocking of their financial transactions (the UN).

On balance, the increasing sophistication of the tools that can harm hostile countries and organizations makes the long-lasting occupation of territories less and less necessary. All that is required is military bases and retention camps from which thousands of soldiers and experts organize the control of large civilian zones on the ground, and collect information on the enemy.

Conclusion

There are three types of intervention: power showing and humanitarian, or a mix of the two.

Interventions of the first type have not slowed down since the end of the Cold War, and have even extended towards the seas and oceans, cyberspace, as well as the extra-atmospheric zone, and perhaps beyond.

Interventions of the second type are multiplying fast, moving step-by-step inland. In most theatres of war, intervention triggers coordination and cooperation.

Interventions of the third type may be more efficient in the short run, but they also entail rejection by local populations in the longer term.

It is therefore tricky to understand the factors that lead to collaboration, rather than encourage the desire for revenge.

Share this

Global Studies: Risks and Threats in International Relations

Global Studies: Risks and Threats in International Relations

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free