Exploring financial barriers to health care

Share this step

“We are not allowed to get sick anymore because we have to pay for medication… what with?”

An older man, Zenica, Bosnia and Hercegovina (excerpt from Narayan et al., 2000, p. 102).

“I have a daughter who came from Esmeraldas with pains in her legs… I have no means to take her to the doctor…that’s why I say that life is sad, because I don’t have any way to pay for a doctor, an injection or anything”

A woman, Isla Trinitaria, Ecuador (excerpt from Narayan et al., 2000, p. 103).

We have discussed the importance of knowing which socio-economic determinants drive inequity in a particular setting and the health services or outcomes with the greatest inequities. However, we also need to understand: why?

One major cause of inequity in access to health services is the cost associated with obtaining healthcare and the inability of disadvantaged populations to pay, also referred to in the literature as financial barriers to health care. One of the major objectives of Universal Health Coverage is to reduce financial barriers and therefore improve equity. It is important to note that financial barriers include not only the official expenses for health services, including for medicines, but also informal expenses for health services, transportation expenses when trying to seek health care, and economic opportunities foregone when seeking health care. There are two repercussions of these financial barriers – individuals either avoid or postpone needed health care, or households incur high amounts of debt or loss of income linked to health care.

A study in China in 2006 found that 30% to 50% of people did not obtain needed treatment because of financial difficulty, the proportion being higher in rural areas and smaller cities (Zhao, 2006), and this pattern is widely observed in other countries.

A related concept is the relationship between economic status and financial barriers: the poor are much more sensitive to financial barriers. So what does this mean? Let’s look at an example from Burkina Faso. A study by Sauerborn et al. (1994) in Burkina Faso found that for a 10% increase in price, utilisation of outpatient health services fell by 7.9%. However, for the poorest groups, utilisation fell by 14%, and by 17% to 36% for infants and children. So the poor and vulnerable reacted more than other population groups to the same increase in price.

Now consider the challenge posed by unofficial (sometimes called informal) payments for health care.

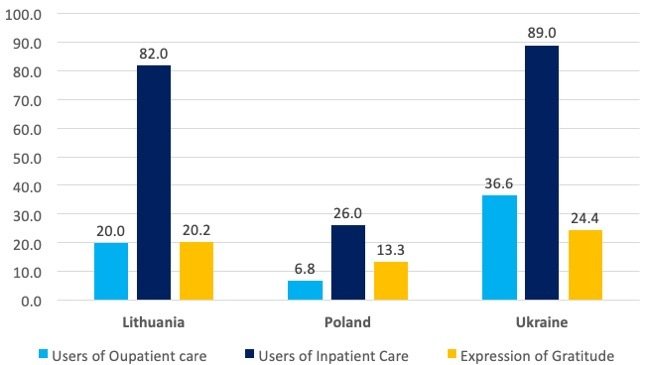

Proportion of users of services reporting payments, and whether payments were an Expression of Gratitude (%).

The graph shown above (created from data available in Stepurko et al., 2015) shows the proportion of users of health services reporting payments (in the previous 12 months), and whether payments were an expression of gratitude (a ‘tip’ or informal payment). The data show that almost 80% of users of inpatient services in Ukraine and Lithuania made informal payments. Moreover, between 10% and 25% of the population using services reported making payments as an expression of gratitude.

It is not just cash payments for health services and drugs that serve as financial barriers. Financial barriers may also take the form of distance and transportation costs.

Masters et al. (2013) found that an increase in one hour of travel time to a health facility for a pregnant woman lowered the likelihood of in-facility deliveries by almost 25% in Ghana. A study from India (Kumar et al., 2014) found that a one kilometre increase in the distance from a health facility lowered the likelihood of in-facility deliveries by 4.5%.

Transportation costs can have a significant impact on household out-of-pocket expenditures when seeking care. In many settings the share of transportation costs is a large component of the total cost of healthcare. Needless to add, this will have an influence on a household’s ability and willingness to seek care.

Another important financial barrier in many settings is the loss of income or the opportunity cost of seeking care. This is particularly hard for informal sector workers where the choice is between earning an income or seeing a doctor. The consequence of this in many settings is that patients wait to seek care until their conditions become more serious, and difficult to treat.

The economic consequences of ill health for households facing financial barriers can be to push them below the poverty line. This is often not defined by the amount households spend on healthcare. Some households fall below the poverty line even when they spend little, because their pre-health-spending incomes were already too low. In this sense, the poor are much more vulnerable to financial barriers than the rich. Often, households sell assets or incur debt to pay for health care, sometimes known as hardship payments, and once again, the proportion of the rich who incur hardship payments is much lower compared to the poor.

What do you think are the most important financial barriers for disadvantaged populations in your country/setting? Will reducing or eliminating user fees and the cost of medicines alone improve financial access for health care? Please use the comments section below to share to share your response with peers.

References

Kumar, S., Dansereau, E.A. and Murray, C.J., 2014. Does distance matter for institutional delivery in rural India?. Applied Economics, 46(33), pp.4091-4103.

Masters, S.H., Burstein, R., Amofah, G., Abaogye, P., Kumar, S. and Hanlon, M., 2013. Travel time to maternity care and its effect on utilization in rural Ghana: a multilevel analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 93, pp.147-154.

Narayan, D., Chambers, R., Shah, M.K. and Petesch, P., 2000. Voices of the Poor: Crying out for Change. New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank.

Sauerborn, R., Nougtara, A. and Latimer, E., 1994. The elasticity of demand for health care in Burkina Faso: differences across age and income groups. Health Policy and Planning, 9(2), pp.185-192.

Stepurko, T., Pavlova, M., Gryga, I., Murauskiene, L. and Groot, W., 2015. Informal payments for health care services: the case of Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine. Journal of Eurasian Studies, 6(1), pp.46-58.

Zhao, Z., 2006. Income inequality, unequal health care access, and mortality in China. Population and Development Review, pp.461-483.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free