Looking at frontispieces

The frontispiece is the name given to the illustration at the very front of a book. Like title pages, which we will be exploring later on in the course, they are considered to be paratexts (text that exists in parallel to, or alongside, the main text within a book). Very often the frontispiece is on the left-hand page (verso), opposite the title page on the right-hand side (recto), and so when the book is laid open, the image and the text of the title page lie side by side. That they can be placed side by side like this encourages us to think about them as having equal status.

Fig 1. Arnaud Berquin, The looking-glass for the mind: or, Intellectual mirror. Being an elegant collection of the most delightful little stories and interesting tales: chiefly translated from that much admired work L’ami des enfans (Dublin, 1788), frontispiece and title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin

Fig 1. Arnaud Berquin, The looking-glass for the mind: or, Intellectual mirror. Being an elegant collection of the most delightful little stories and interesting tales: chiefly translated from that much admired work L’ami des enfans (Dublin, 1788), frontispiece and title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin

This exceptionally beautiful frontispiece was engraved by J. McDonnell and it establishes a certain mood for the book that follows. The lady and her children at the centre of the image are surrounded by mythical and allegorical figures, suggesting that this book brings readers into contact with the allegorical and the magical.

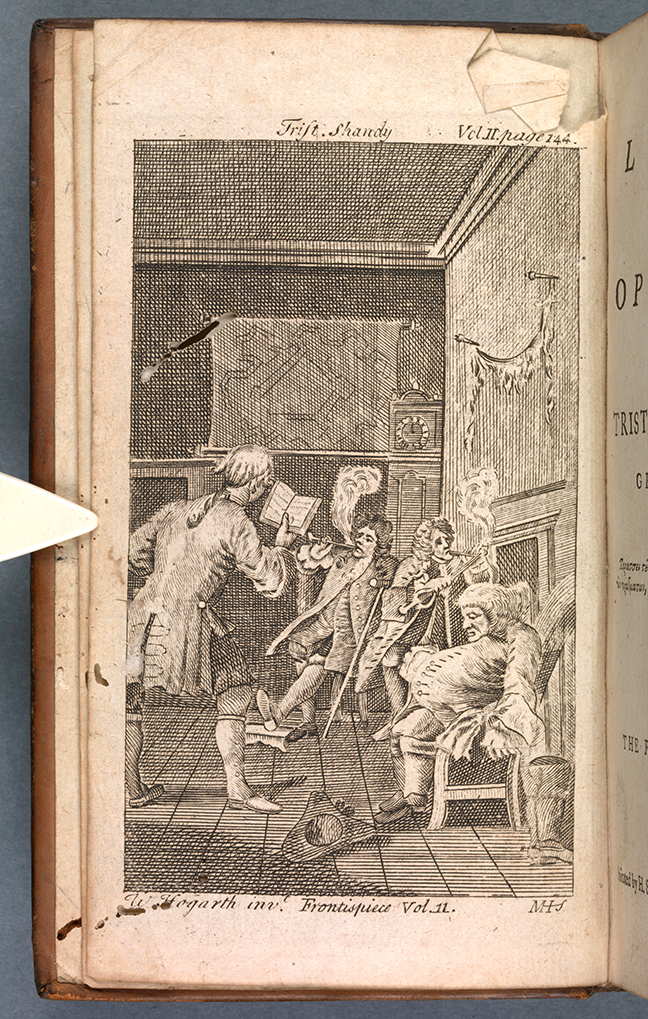

Like the title page, the frontispiece gives us vital clues as to what the book contains. In fictional texts, the frontispiece is often an illustration of a key scene from the narrative. In this frontispiece for Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman designed by William Hogarth, we see a scene with characters from the novel. This is the only illustration from this book and the frontispiece plays an important role in helping us to visualise the characters, their personalities, and their relationships even before we start reading.

Fig 2. Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (London, 1780), i, frontispiece © Wikimedia

Fig 2. Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (London, 1780), i, frontispiece © Wikimedia

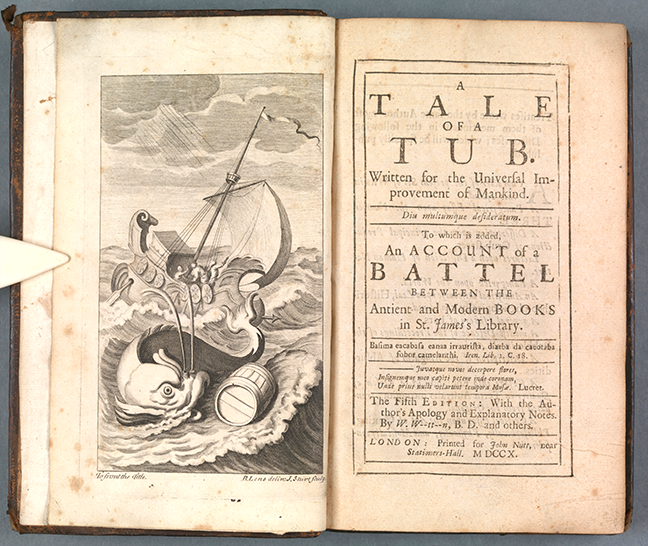

In the 17th century, developments in image-making technologies enabled printers to create increasingly elaborate and attractive illustrations using sophisticated engravings to produce eye-catching and beautiful effects. The frontispiece is sometimes the only illustration in a book and so publishers used the frontispiece to attract the reader’s attention and to advertise the contents of the book.

This frontispiece from Jonathan Swift’s The Tale of a Tub shows us a dramatic scene, when a whale threatens to overturn a ship. In this book the scene is a complex metaphor – the ship is not an ordinary sailing vessel but “the Ship of State” and the whale that threatens it is the Leviathan, which references Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil (1651). The book is the “tub” that the sailors on the beset ship throw overboard to distract the whale (and by extension, the ordinary people who might threaten to overwhelm the state).

Fig 3. Jonathan Swift, A tale of a tub: Written for the universal improvement of mankind … To which is added, An account of a battel between the antient and modern books in St. James’s Library. (London, 1710), frontispiece and title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 3. Jonathan Swift, A tale of a tub: Written for the universal improvement of mankind … To which is added, An account of a battel between the antient and modern books in St. James’s Library. (London, 1710), frontispiece and title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

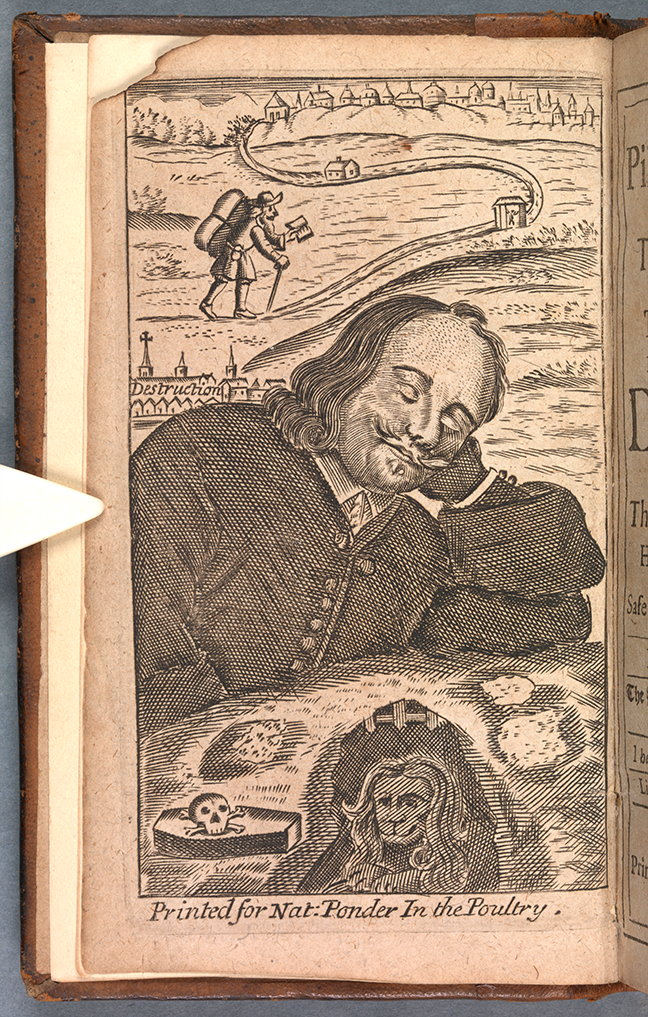

Other frontispieces show portraits of the book’s author. This is especially common when the author was famous or noteworthy in some way. This frontispiece for John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress is unusual because it merges the portrait with the illustrated scene. Here, we see the poet, Bunyan, asleep and dreaming about the adventures of Pilgrim as he makes his way through the world towards heaven and salvation.

Fig 4. John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress from this World to that Which is to Come: Delivered Under the Similitude Of A Dream: Wherein is Discovered, The Manner of His Setting Out, His Dangerous Journey, and Safe Arrival at the Desired Country (London, 1710), frontispiece. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 4. John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress from this World to that Which is to Come: Delivered Under the Similitude Of A Dream: Wherein is Discovered, The Manner of His Setting Out, His Dangerous Journey, and Safe Arrival at the Desired Country (London, 1710), frontispiece. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

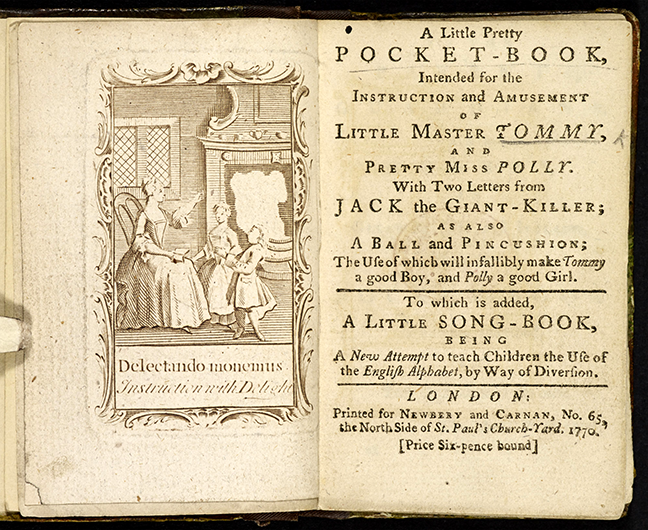

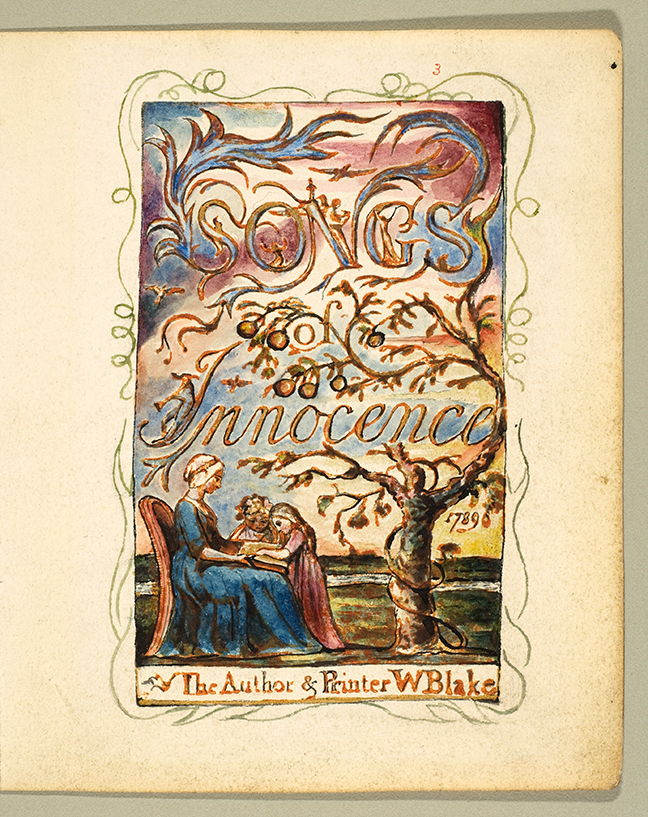

In children’s books like John Newbery’s A Little Pretty Pocket Book (1744) and in books about childhood like Blake’s Songs of Innocence (1789), the frontispiece often presents an idealised image of the child reader. In many cases, the child is shown standing beside a parent-figure (usually their mother) and they read the book together. These frontispieces do not show us what the book is about but rather suggest how the book is intended to be read.

Fig 5. John Newbery, A Little Pretty Pocket Book (London, 1744) © British Library

Fig 5. John Newbery, A Little Pretty Pocket Book (London, 1744) © British Library  Fig 6. William Blake, Songs of Innocence (London, 1789), frontispiece © Wikimedia

Fig 6. William Blake, Songs of Innocence (London, 1789), frontispiece © Wikimedia

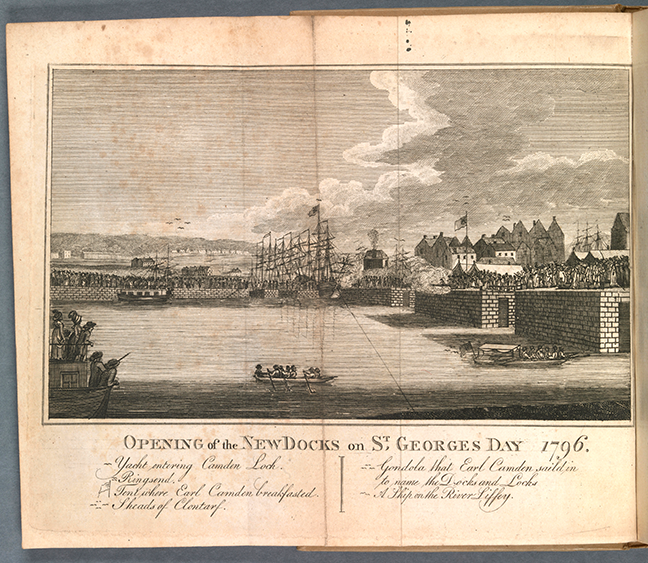

This unusual double-page frontispiece shows the docks at Dublin – unlike the imaginary scenes depicted in some of the other frontispieces we’ve looked at, this is a real scene captured in exquisite detail. This gives us an immediate sense of the geographical and historical context for the book.

Fig 7. Jane Elizabeth Moore, Miscellaneous poems on various subjects (Dublin, 1796), frontispiece. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin

Fig 7. Jane Elizabeth Moore, Miscellaneous poems on various subjects (Dublin, 1796), frontispiece. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin

Whether they depict real or imaginary scenes, frontispieces play an important role in establishing the tone and context for a book. As they appear at the very start of a book, we can consider them as a kind of threshold: once we pass this page, we enter into the book itself. While it may be tempting to skip ahead to the first chapter, it is worth to examine the frontispiece carefully and to consider how it frames the book and sets up our expectations for what we are about to read.

-

Choose one of the frontispieces for the texts below and say what expectations it creates for the book.

- Jonathan Swift, A Tale of a Tub (London, 1710). Source: British Library

- William Blake, Songs of Innocence (1789). Source: Wikisource

Here are three versions of The Pilgrim’s Progress. Fashions in frontispieces have changed over time and these may set up very different expectations about the book.

- John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress (London, 1815). Source: British Library

- John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress (Philadelphia, 1909). Source: Wikisource

- John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress (1890). Source: Wikisource

- John Newbery, A Little Pretty Pocket Book (Massachusetts, 1787). Source: Wikisource

Dr Jane Suzanne Carroll, School of English, Trinity College Dublin.

Share this

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free