Home / History / Social History / The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800 / Connoisseur collectors

This article is from the free online

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Fig 1. Jean Grolier’s copy of Desiderius Erasmus’ Pacis Querela (Venice, 1518), title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 1. Jean Grolier’s copy of Desiderius Erasmus’ Pacis Querela (Venice, 1518), title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

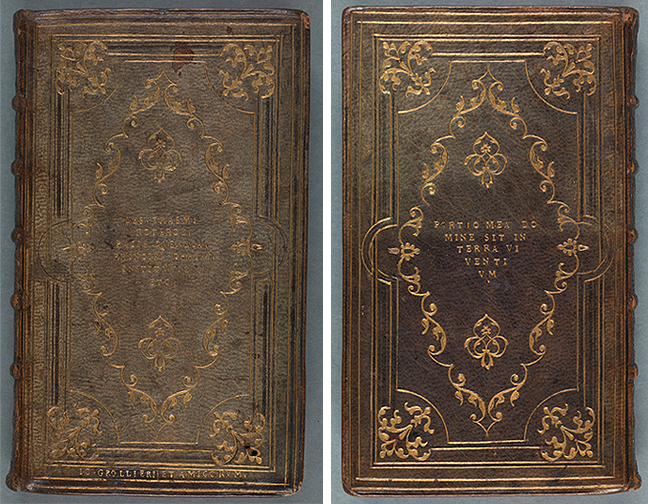

Fig 2. Jean Grolier’s copy of Desiderius Erasmus’ Pacis Querela (Venice: Aldine press, 1518), front and back cover. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 2. Jean Grolier’s copy of Desiderius Erasmus’ Pacis Querela (Venice: Aldine press, 1518), front and back cover. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

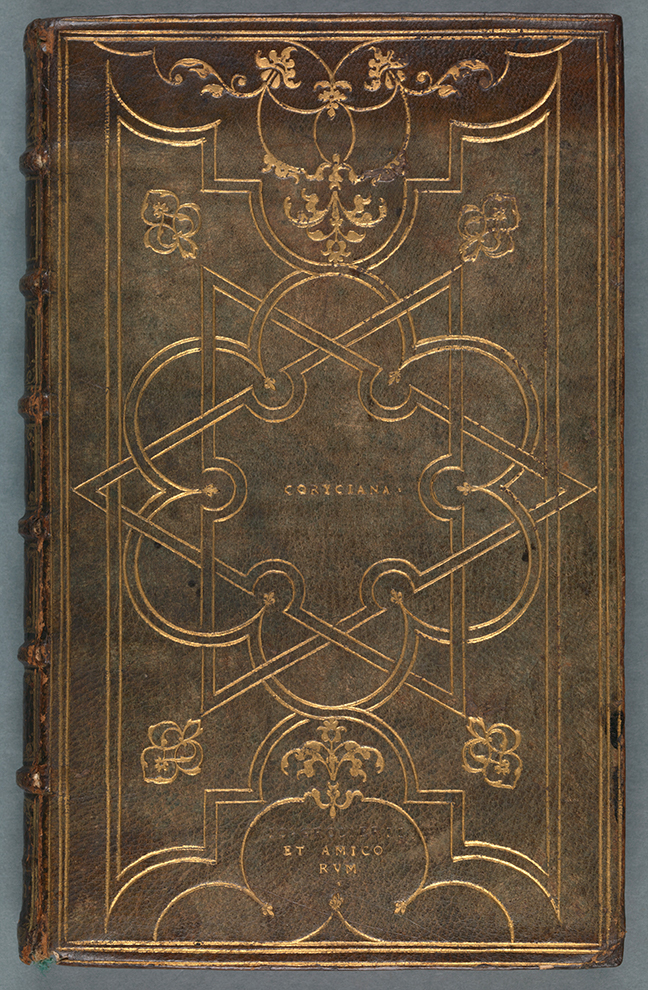

Fig 3. Jean Grolier’s copy of Blosius Palladius, Coryciana (Rome, 1524), front cover. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 3. Jean Grolier’s copy of Blosius Palladius, Coryciana (Rome, 1524), front cover. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

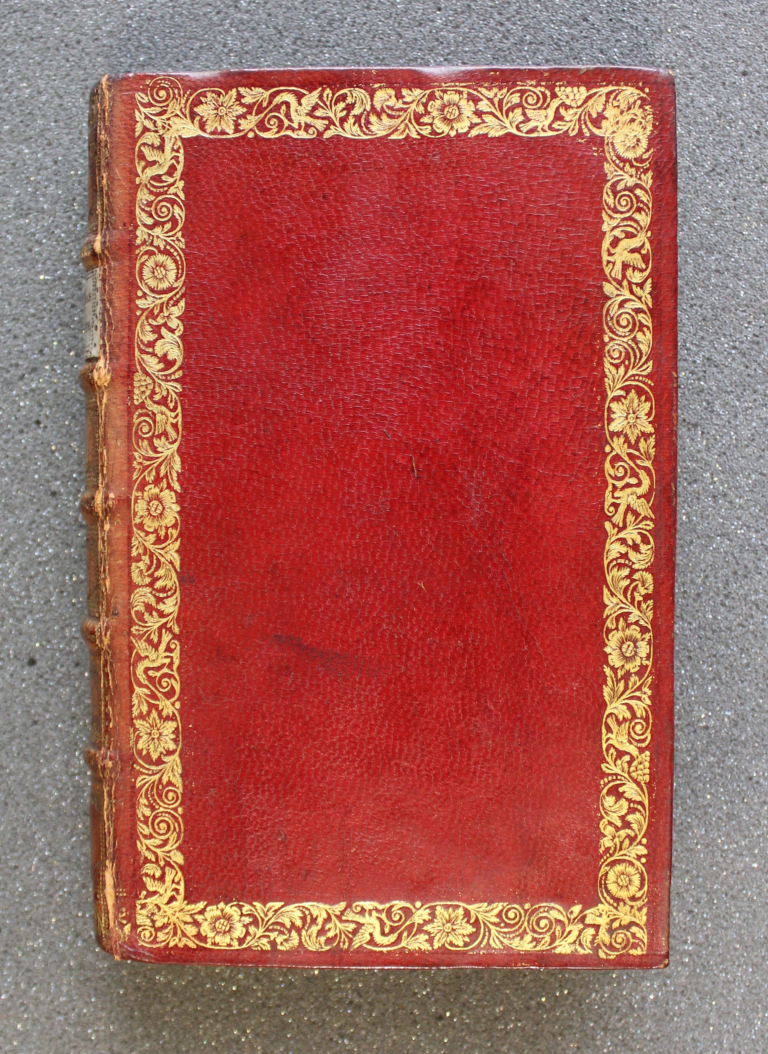

Fig 4. An early eighteenth-century Dutch binding on Hendrik Adriaan vander Marck’s copy of Catullus. Tibullus. Propertius (Paris, 1534). © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Fig 4. An early eighteenth-century Dutch binding on Hendrik Adriaan vander Marck’s copy of Catullus. Tibullus. Propertius (Paris, 1534). © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

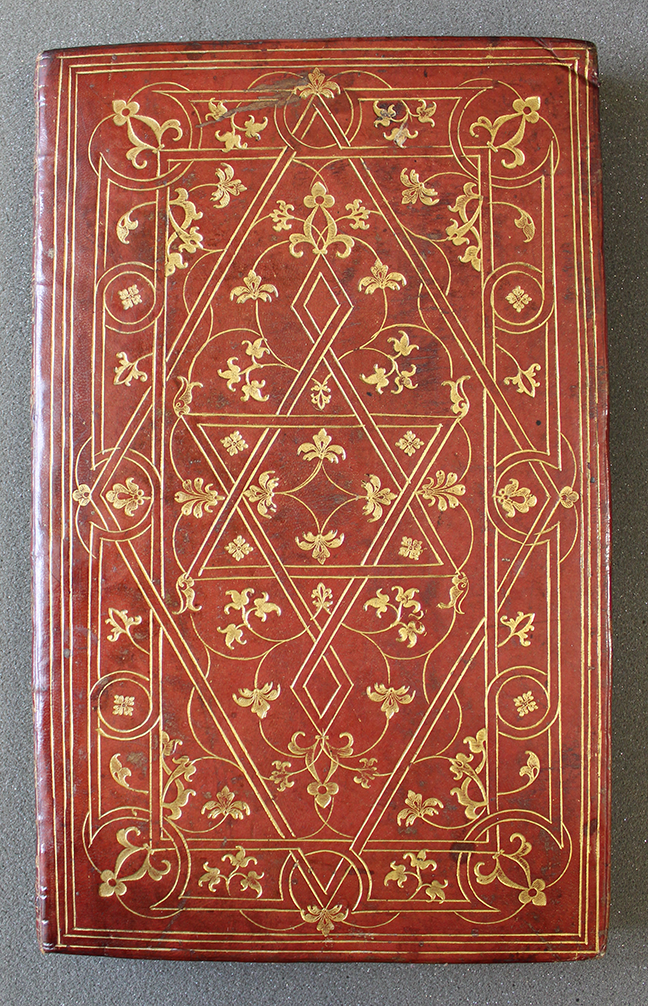

Fig 5. A mid-sixteenth-century French binding on Worth’s copy of Herodotus, Historiae lib. IX (Geneva, 1566). © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Fig 5. A mid-sixteenth-century French binding on Worth’s copy of Herodotus, Historiae lib. IX (Geneva, 1566). © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.