Protestantism, Print and Politics: The Early Modern Bible

The Bible, the bestselling book of all time, had a captivating political history during the time of the Reformation. Publishing the Bible in the language of the people was a key priority for reformers in the early modern period.

Sola scriptura, Scripture alone, was one of the central tenets of the Reformation across Europe, and if the common people were to have their religious and spiritual lives guided by the Bible, rather than the teachings of the Church, they would need to read the Bible in their mother tongue. It is not surprising, that the sixteenth century saw a wave of Bible translations being published.

Fig 1. Hans Holbein, Portrait of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam with Renaissance Pilaster. Source: Wikipedia

Fig 1. Hans Holbein, Portrait of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam with Renaissance Pilaster. Source: Wikipedia

Although these translations were one of the key hallmarks of the Reformation, ironically they all had their roots in the scholarship of a man who was deeply and bitterly opposed to the Reformers. Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) was critical of many of the abuses of the early modern Catholic Church, but he believed that these issues should be addressed within the structures of the Church. He thought that a new Latin translation of the Bible would be an important step towards the purification of the Church.

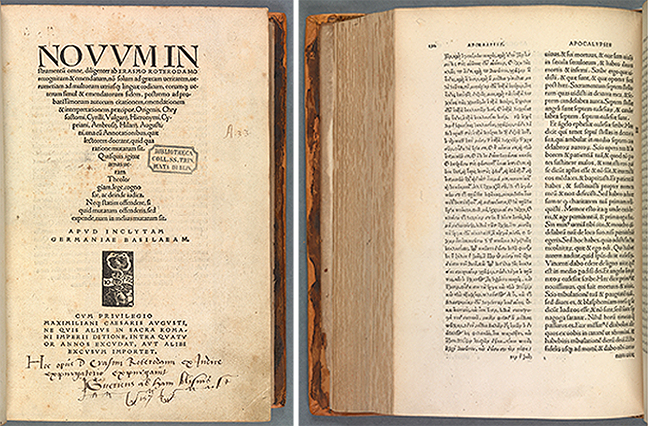

Since the late fourth century, the Vulgate, a translation of the Hebrew Old Testament and Greek New Testament into Latin undertaken by Jerome (d. 420), had been the dominant version of the Bible – essentially the only version of the Bible that was available in medieval Europe. Although acknowledging that the Vulgate was an impressive achievement of scholarship, Erasmus argued that it was prone to error, both in its translation, and its transmission (unsurprisingly, when we remember that, before printing, every copy had to be made by hand). To address this problem, Erasmus set out on an ambitious project – a new translation of the Bible into Latin, which would be based on a new edition of the Greek text. The resulting edition, the Novum Instrumentum omne was published in 1516. It featured a parallel setting of the Greek and Latin text, accompanied by Erasmus’s commentary.

Fig 2. On the left is the title page of Novum Instrumentum omne (Basel, 1516); on the right is Novum Instrumentum omne (Basel, 1516), p. 192, showing part of the text of Revelation. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin. (Click to expand)

Fig 2. On the left is the title page of Novum Instrumentum omne (Basel, 1516); on the right is Novum Instrumentum omne (Basel, 1516), p. 192, showing part of the text of Revelation. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin. (Click to expand)

Neither Erasmus’ edition nor his translation was perfect. He completed the project in something of a rush, in order to beat a similar Spanish project, the Complutensian Polyglot, to the market. This rush to publish meant that Erasmus’ salesmanship overwhelmed his scholarship, but it did mean that he was successful in securing an exclusive four-year publishing privilege for the Greek New Testament from Emperor Maximilian (1459-1519) and Pope Leo X (1474-1521).

Whatever its failings might have been, the Novum Instrumentum omne (known in later editions as the Novum Testamentum omne) became a vital tool for the reformers as they translated the Bible into the vernacular languages of Europe. Erasmus’ Greek text provided a basis for most of the translations that appeared during the course on the sixteenth century.

Martin Luther translated the New Testament into German in 1522, and his translation of the whole Bible into German was published in 1534.

Fig 3. Das Allte Testament deutsch (Wittenberg, 1523), title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 3. Das Allte Testament deutsch (Wittenberg, 1523), title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Lefèvre d’Etaples (1450-1536) led the way with his translation of the Bible into French in 1530. This was followed in 1535 by another translation, which is often known as Olivétan’s Bible, after the name given to its translator Pierre Robert Olivétan (1506-1538).

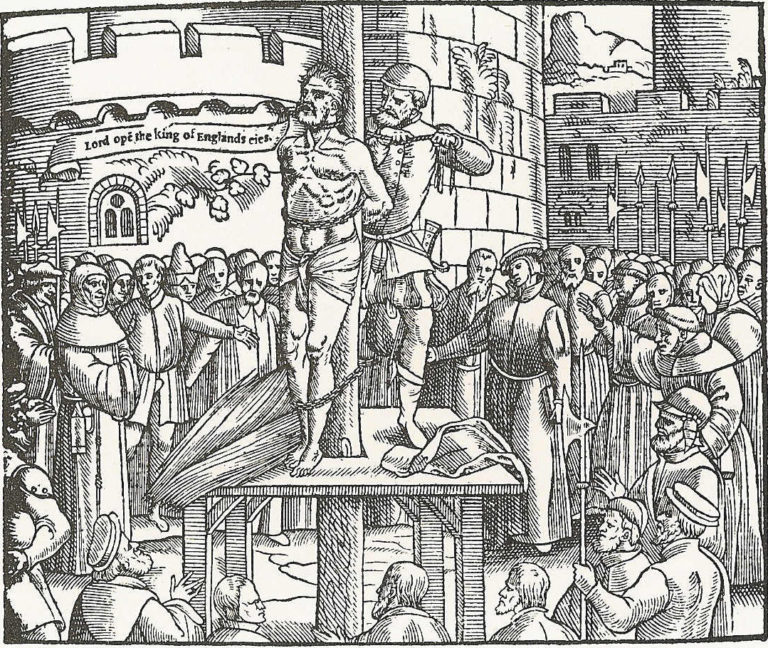

Although the Bible had been translated into English by the followers of John Wycliffe (1330-1384), the first early modern translation was undertaken by William Tyndale (c. 1494–1536). Because Bible translation was illegal in England without the permission of a bishop, Tyndale did his work as an exile, constantly on the move around Europe, evading capture by agents of the Roman Catholic Church. In spite of these less than ideal circumstances Tyndale succeeded in translating the New Testament, publishing the first edition in 1525. He subsequently revised this and, having learned Hebrew, embarked on the translation of the Old Testament. His work on this was cut short by his betrayal and arrest. On 6 October 1536, he was executed by strangling before his body was burned. His last words were a prayer: ‘Lord! open the King of England’s eyes’.

Fig 4. Preparations to burn the body of William Tyndale in John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (London, 1563). This image, from the copy in the Folger Shakespeare Library, was reproduced in L.B. Smith, The Horizon Book of the Elizabethan World (American Heritage / Houghton Mifflin, 1967), p. 73. © Wikimedia.

Fig 4. Preparations to burn the body of William Tyndale in John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (London, 1563). This image, from the copy in the Folger Shakespeare Library, was reproduced in L.B. Smith, The Horizon Book of the Elizabethan World (American Heritage / Houghton Mifflin, 1967), p. 73. © Wikimedia.

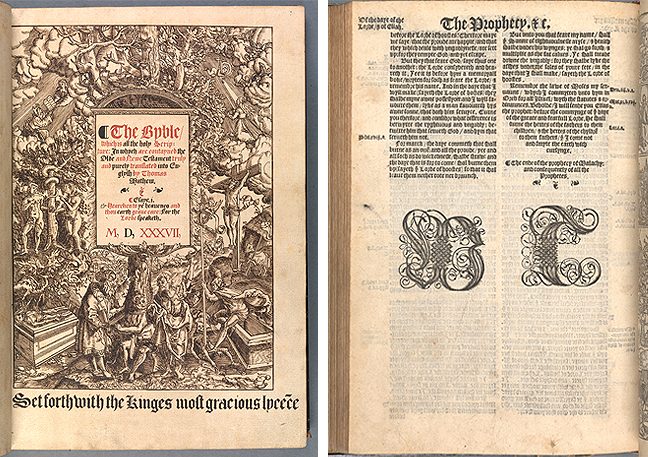

Tyndale’s New Testament was illegal in England, although it was smuggled into the country in considerable quantities. It is ironic that, less than a year after his death, Tyndale’s translations became the basis for the first English Bible to be published with royal permission. The Matthew Bible combined Tyndale’s New Testament with as much of his Old Testament translation that had been completed by his death and a translation of the remainder of the Old Testament and Apocrypha by Miles Coverdale (1488-1569). The Matthew Bible pays covert homage to Tyndale’s involvement in the ornate initials WT that appear at the end of the Old Testament.

Fig 5. On the left is the title page of the The Byble, which is all the holy Scripture (Matthew Bible) (Antwerp, 1537). On the right is the ornate WT following the ending of the Book of Malachi © The Board of Trinity College Dublin. (Click to expand)

Fig 5. On the left is the title page of the The Byble, which is all the holy Scripture (Matthew Bible) (Antwerp, 1537). On the right is the ornate WT following the ending of the Book of Malachi © The Board of Trinity College Dublin. (Click to expand)

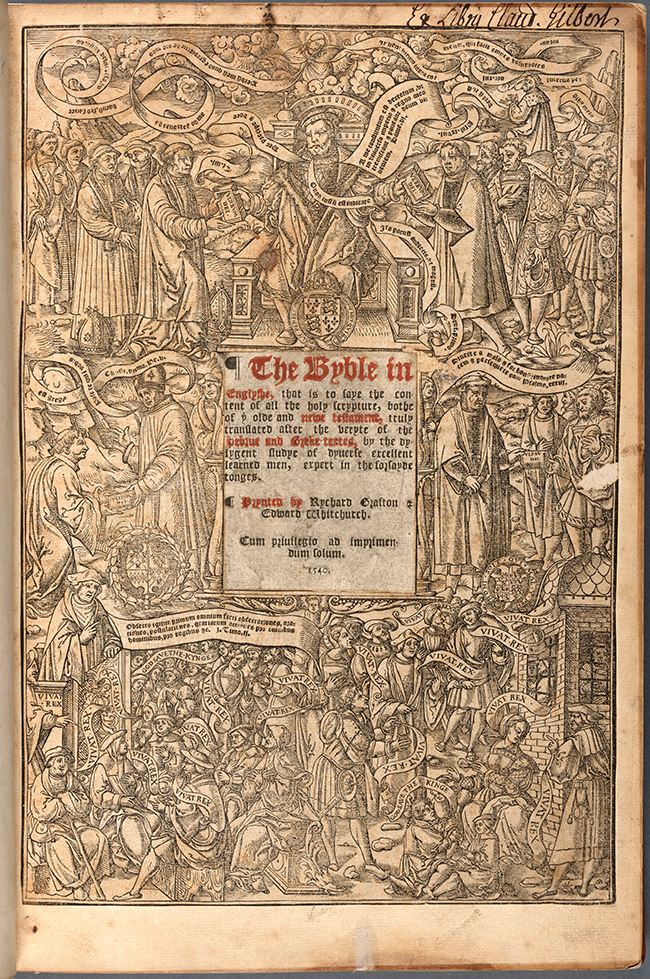

The religious and political climate of England continued to evolve rapidly in the years after Tyndale’s death. By 1539 the landscape had changed dramatically. Henry VIII (1491-1547) had broken with Rome and, in a demonstration of his new authority over the English church, Henry authorised a new translation of the Bible for use in English churches. This edition, the Great Bible, was heavily dependent on Tyndale’s work, as, indeed, were most English translations since. It features a fascinating frontispiece, depicting an enthroned Henry, distributing the Bible to Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), on the left, and Thomas Cromwell (c. 1485-1540) on the right. At this point in his reign, Henry clearly felt that it would be beneficial to be identified as the champion of a project that he had long opposed – the provision of a Bible in English.

Fig 6. The Byble in Englyshe … (The Great Bible) (London, 1540), title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 6. The Byble in Englyshe … (The Great Bible) (London, 1540), title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

- Tyndale’s translation of John 3:16 Reads as follows: For God so loveth the worlde yt he hath geven his only sonne that none that beleve in him shuld perisshe: but shuld have everlastinge lyfe.

- Compare the rendering of this verse in a number of modern versions. You may like to use the Bible Hub Tool tool to help you.

- At the top of the Bible Hub page there is a blank search box. Enter “John 3:16” into this box.

- Underneath the search box you can select which bible versions you would like to compare using the two dropdown version boxes.

Dr Mark Sweetnam, School of English, Trinity College Dublin

Share this

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free