History of the Book: Understanding Religious Texts

In this article, we will be looking at how books changed the world.

That may seem like a very big claim – and it is. But there is no doubt that people’s understanding of the world and of their place within it did change dramatically in the early modern period. New methodologies and new discoveries in the fields of astronomy, medicine and science reshaped people’s conception of the universe at every level, while the reformation challenged, and in some cases, transformed long cherished beliefs about God and man and the relationship between them. And all of these ideas – exciting, revolutionary, and terrifying – circulated in books.

Of course, not everyone could read books. Although levels of literacy were increasing rapidly in early modern Europe, there were still a great many people who couldn’t read. This posed something of a problem for Protestants. Early modern Catholicism was well equipped to cater for people who couldn’t read – or who were unable to understand the Latin in which services were conducted. Its stained glass and paintings, its images and sculpture, and even its vestments and liturgy were visual – unless you wanted to be a priest (and sometimes not even then) literacy was neither here or there.

In general, Protestants had two problems with emulating this success. Firstly, it had shifted the emphasis of religious life firmly in the direction of the Word of God. This was now read and expounded in a language that people could understand, but there is no doubt that these stripped-down, sermon-centred services lacked much of the visual oomph that the faithful had been accustomed to. Secondly, Protestantism was generally iconoclastic – it objected to depictions of divine persons, and to depictions of many of the saints and miracles that were a standard part of Catholic iconography. This iconoclasm left a particular mark in England, where Thomas Cromwell (d. 1540), Henry VIII’s right-hand man, led an official campaign of seizing and destroying objectionable images.

Protestantism, then, faced something of a visual vacuum. It addressed this by turning to two sources of arresting – and edifying – visual material: the Bible and the lives (or, more accurately, the deaths) of the Christian martyrs.

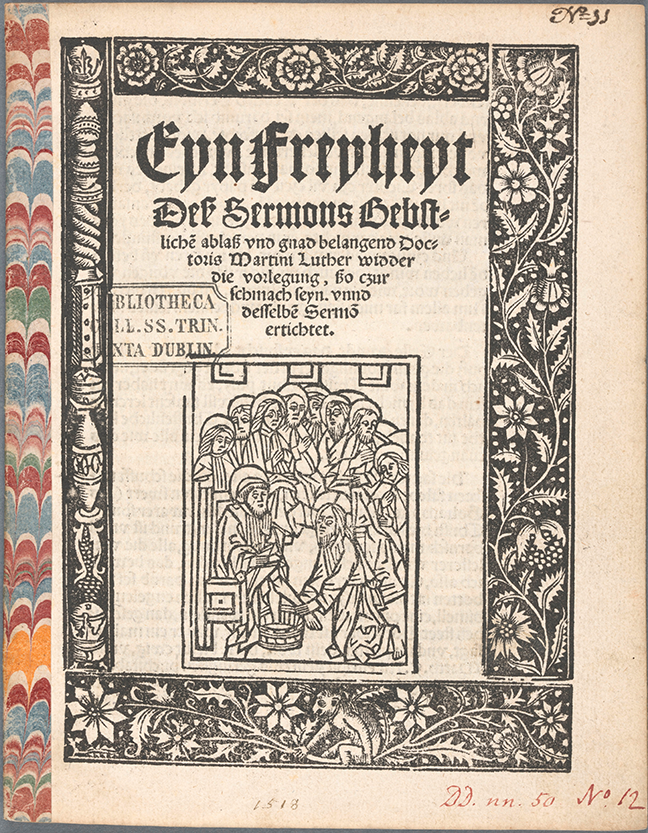

These were fertile sources of visual imagery that was used by the Reformers to broaden the appeal of their message. Luther (1483-1546) was a pioneer in this regard, working closely with artists, especially his friend Lucas Cranach the Elder (d. 1553), who provided illustrations for his works. The image shown here, from one of his first pamphlets, shows an early example of this.

Fig 1. Martin Luther, Eyn Freyheyt Dess Sermons Bebstlichen ablass vnd gnad belangend (Leipzig, 1518), title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 1. Martin Luther, Eyn Freyheyt Dess Sermons Bebstlichen ablass vnd gnad belangend (Leipzig, 1518), title page. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

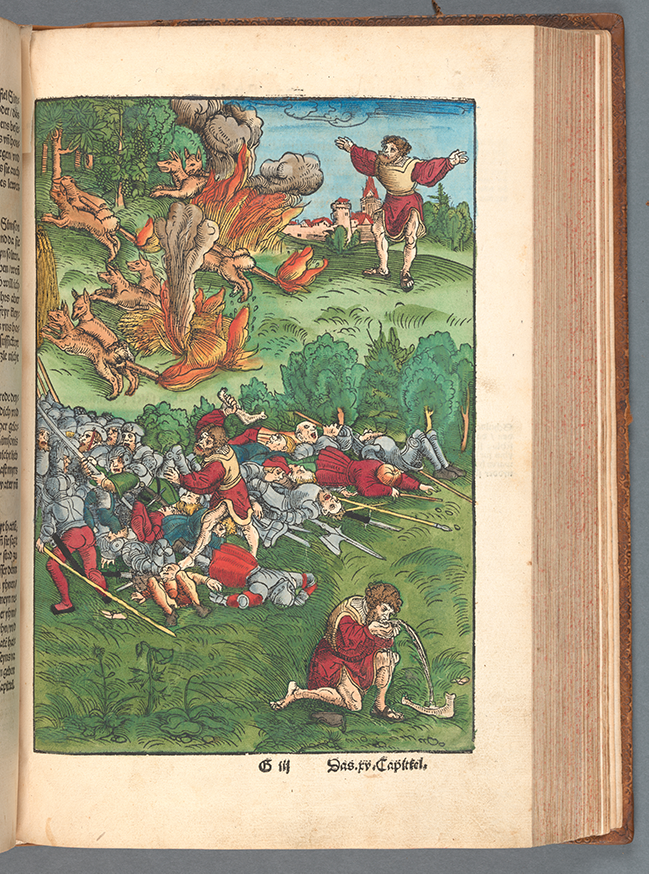

The use of Biblical imagery to reinforce the teaching of Scripture reached an impressive level in the 1523 edition of the German Old Testament, which, as well as an elaborate title page featured eye-catching hand-coloured wood cut images illustrating Old Testament narratives. This image provides a composite view of some of the more lurid incidents in the life of Samson. It is striking that these events are depicted in what is clearly an early-modern German landscape, populated by figures dressed in contemporary clothing. This brought the world of the Old Testament visually up-to-date, underlining the continuing relevance of the Biblical narrative for sixteenth-century Protestants.

Fig 2. Das Allte Testament deutsch (Wittenberg, 1523), Sig. G3r., showing scenes from the life of Samson. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 2. Das Allte Testament deutsch (Wittenberg, 1523), Sig. G3r., showing scenes from the life of Samson. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Protestants were uneasy about religious art, but they were firmly and implacably opposed to the veneration of saints. They regarded the adoration of saints and the attendant collection of relics as one of the foremost abuses of the Church with which they had broken. But if this attitude meant that a great deal of superstition could be abandoned, it also meant that the lives of the saints could no longer serve as useful models of how the individual Christian might live as they ought. Protestants filled the gap left by the saints with martyrs – those who had, since the earliest days of the church, died for their belief. This allowed Protestants to outline an alternative succession of true religion down the centuries – not from pope to pope, but from persecuted group to persecuted group. And, as the persecution was first by the Roman empire and then by the Roman church, it allowed contemporary Protestants to explain and justify the sufferings of their co-religionists as part of a cosmic battle.

Fig 3. John Foxe, Acts and monuments of matters most special and memorable happening in the Church (London, 1684), fold-out in volume 1 showing ‘A most exact Table of the first ten Persecutions of the Primitive Church under the Heathen Tyrants of Rome.’ © The Board of Trinity College Dublin. (Click to expand)

Fig 3. John Foxe, Acts and monuments of matters most special and memorable happening in the Church (London, 1684), fold-out in volume 1 showing ‘A most exact Table of the first ten Persecutions of the Primitive Church under the Heathen Tyrants of Rome.’ © The Board of Trinity College Dublin. (Click to expand)

And the martyrs and their gory deaths made for great visual material, which would grab the interest of the illiterate, and provide vivid lessons in the perfidy of Rome and the endurance of the saints. These woodcuts are taken from John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church, better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.

It was first published in 1563 and, with over sixty woodcuts, was the largest publishing project to have been undertaken in England. The book has a complex publishing history – new material was added in many of the subsequent editions, and it remains in print today. For those who read it, its text provided a history of the Christian church since the first century, with a particular emphasis on the history of the reformation.

Its real impact, however, was visual – its woodcuts of the twisted and tortured bodies of Christians, and its depictions of Protestant heroes bravely preaching and praying from amongst the flames shaped how generations of English Christians saw themselves, their church, and their world.

Fig 4. John Foxe, Acts and monuments of matters most special and memorable happening in the Church (London, 1684), ii, p. 562 showing the martyrdom of Thomas Cranmer. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 4. John Foxe, Acts and monuments of matters most special and memorable happening in the Church (London, 1684), ii, p. 562 showing the martyrdom of Thomas Cranmer. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

- What Bible story do you think would make an effective visual image?

Dr Mark Sweetnam, School of English, Trinity College Dublin

Share this

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free