Home / History / Social History / The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800 / Looking at type design

This article is from the free online

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

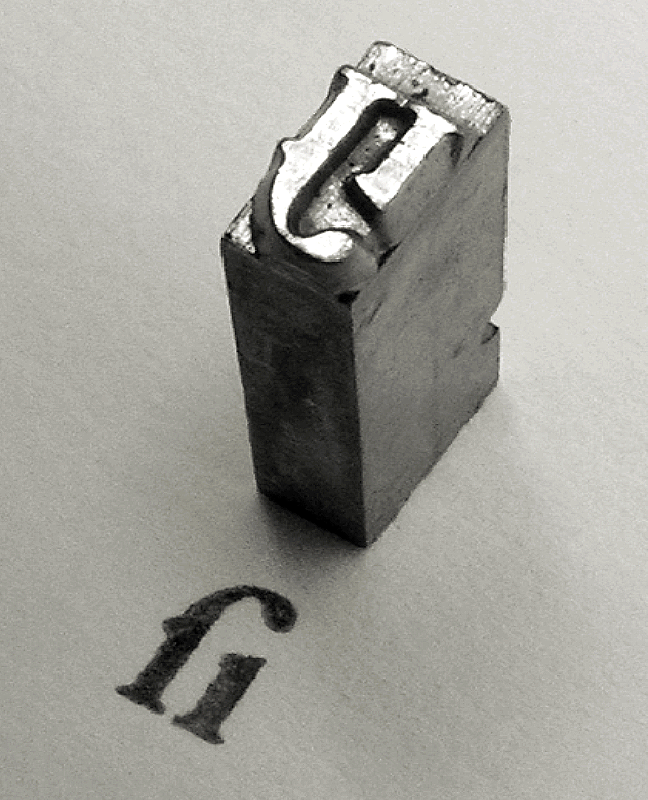

Fig. 1. A ligature of long S and I. Photo: Daniel Ullrich, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 1. A ligature of long S and I. Photo: Daniel Ullrich, CC BY-SA 3.0.

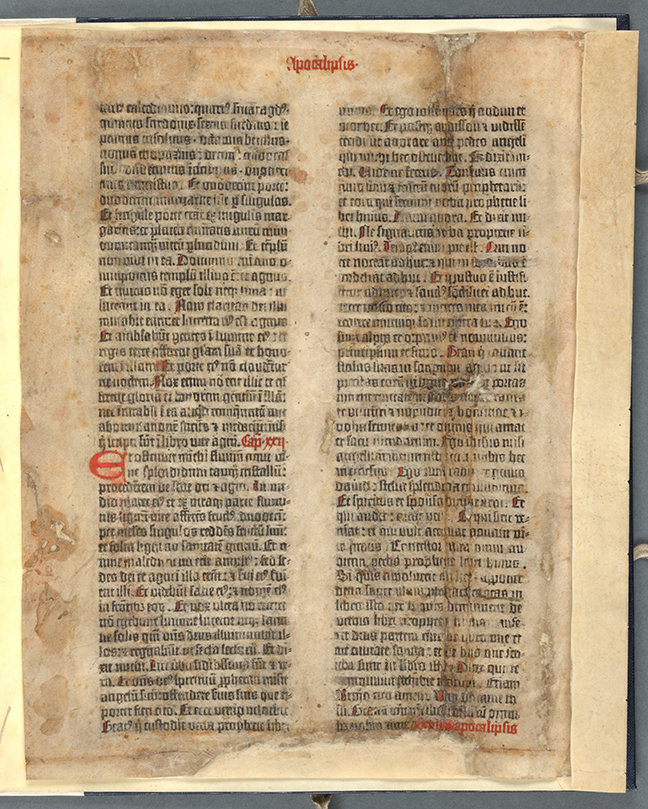

Fig 2. An example of blackletter type: Gutenberg Bible, fol. 317v. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 2. An example of blackletter type: Gutenberg Bible, fol. 317v. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

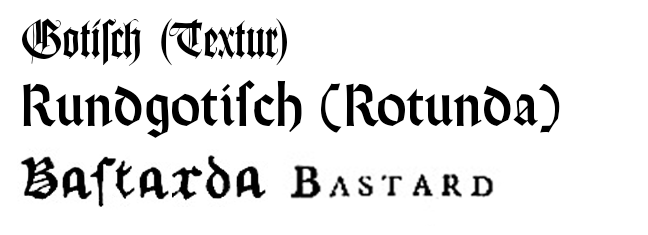

Fig 3. An example of roman type: Plutarch, Vitae Virorum Illustrium (Venice, 1478), i, fol. 1r. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 3. An example of roman type: Plutarch, Vitae Virorum Illustrium (Venice, 1478), i, fol. 1r. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

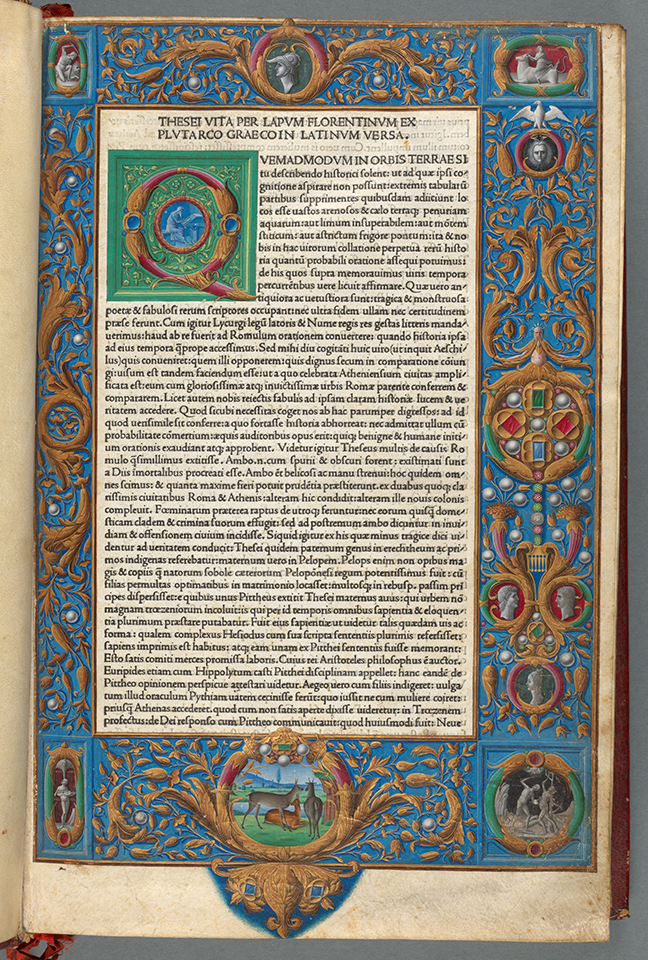

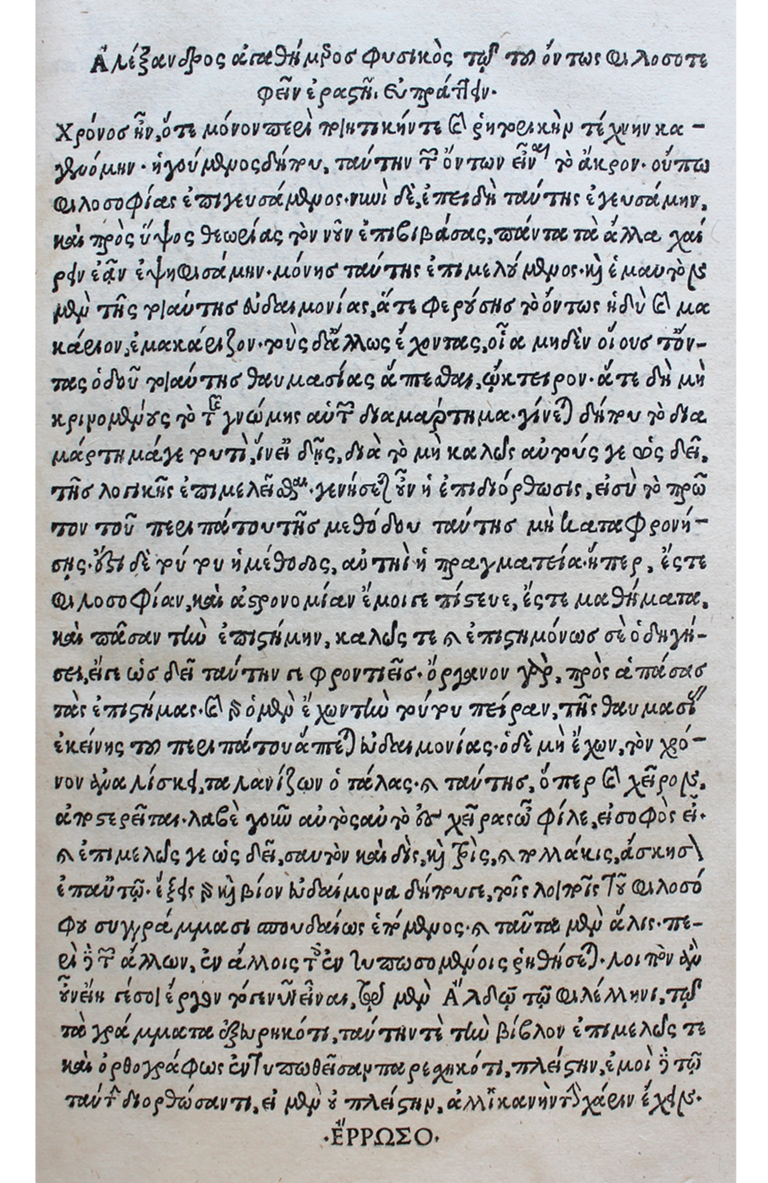

Fig 4. The Aldine ‘Aristotle’ typeface. Aristotle, Eis Organon Aristotelous (Venice, 1495), vol. 1. Sig. A2r. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

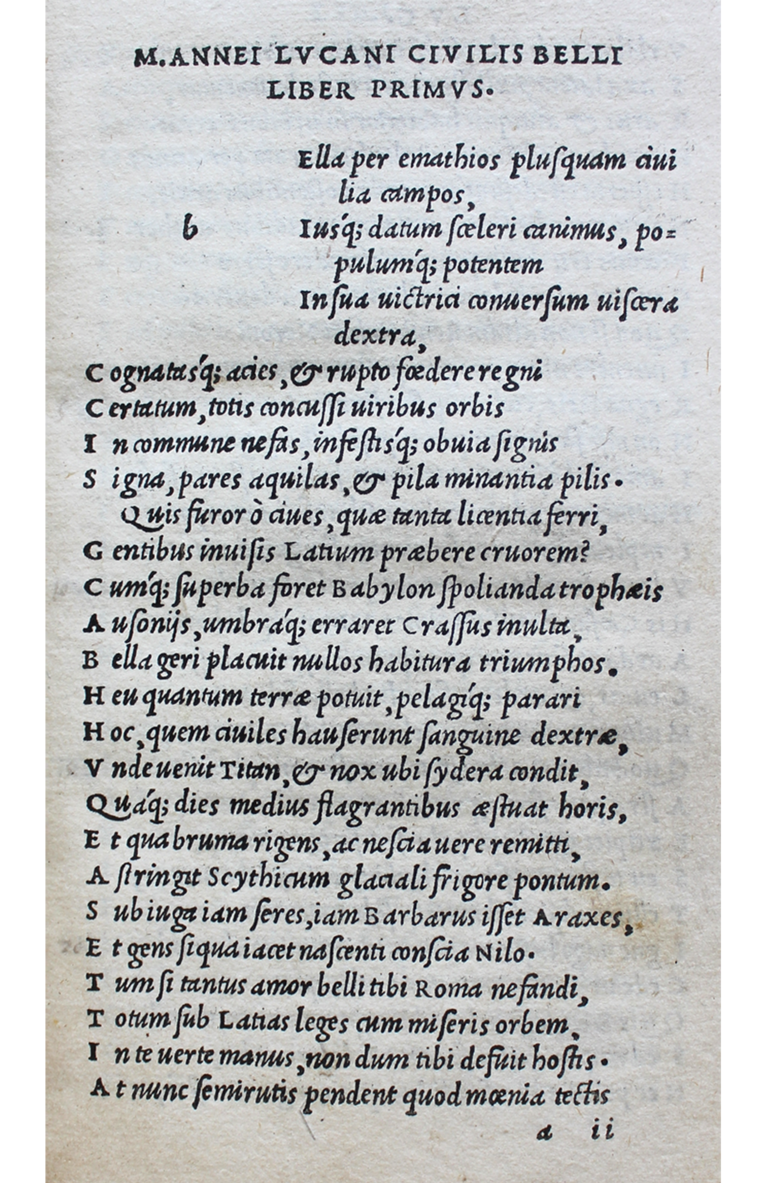

Fig 4. The Aldine ‘Aristotle’ typeface. Aristotle, Eis Organon Aristotelous (Venice, 1495), vol. 1. Sig. A2r. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.  Fig 5. An example of the Aldine italic type in Lvcanvs (Venice, 1502). © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

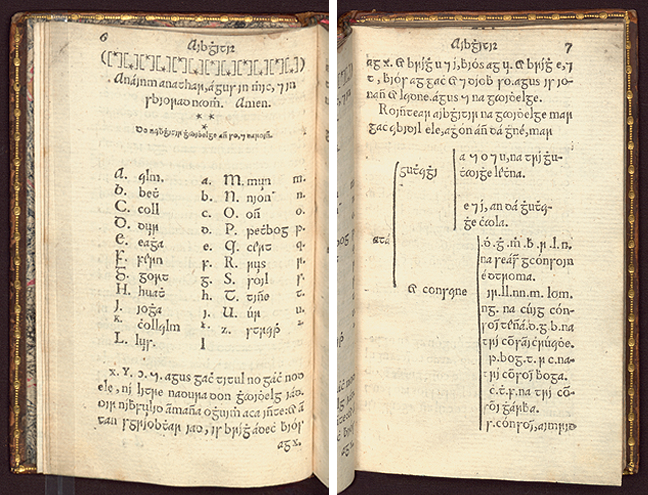

Fig 5. An example of the Aldine italic type in Lvcanvs (Venice, 1502). © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.  Fig 6. John Kearney, Aibidil Gaoidheilge agus caiticiosma (Dublin, 1571), pp 6-7. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.

Fig 6. John Kearney, Aibidil Gaoidheilge agus caiticiosma (Dublin, 1571), pp 6-7. © The Board of Trinity College Dublin.