Home / History / Social History / The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800 / Looking at prefaces

This article is from the free online

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

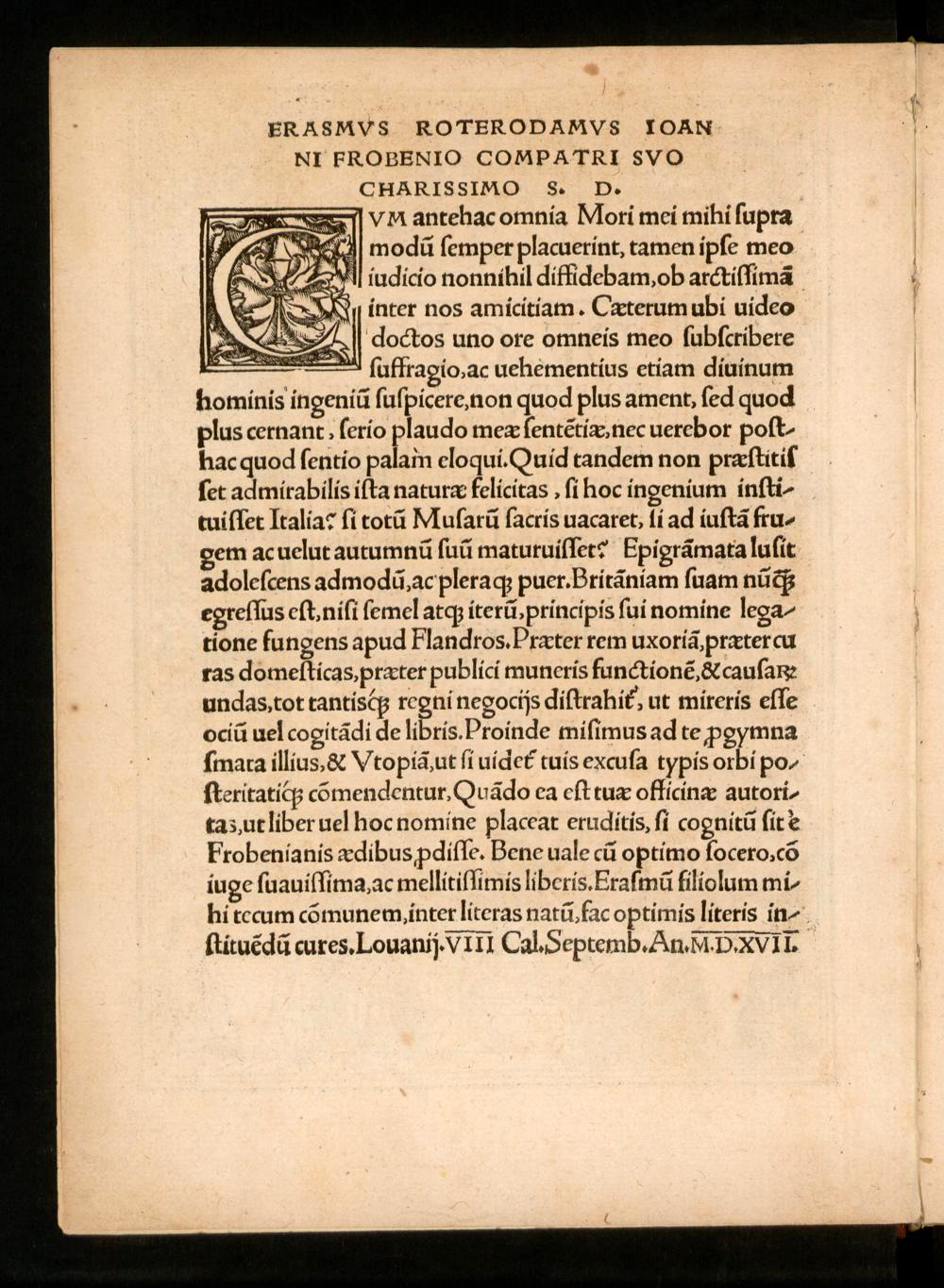

On the right is Thomas More’s letter to Peter Giles in More’s *De optimo reip. statu, deque noua insula Vtopia…* (Basel, 1518). p. 17. [(Click to expand)](https://ugc.futurelearn.com/uploads/assets/f8/28/f828da44-3022-4638-85d6-68d9ef5a3ac2.png)](https://cdn-wordpress-info.futurelearn.com/info/wp-content/uploads/e36fa73f-0b2e-4ad3-a5cc-e1fb370b3b42.png) Fig 1. On the left is Erasmus’ letter to John Froben in Thomas More’s De optimo reip. statu, deque noua insula Vtopia… (Basel, 1518), title verso.

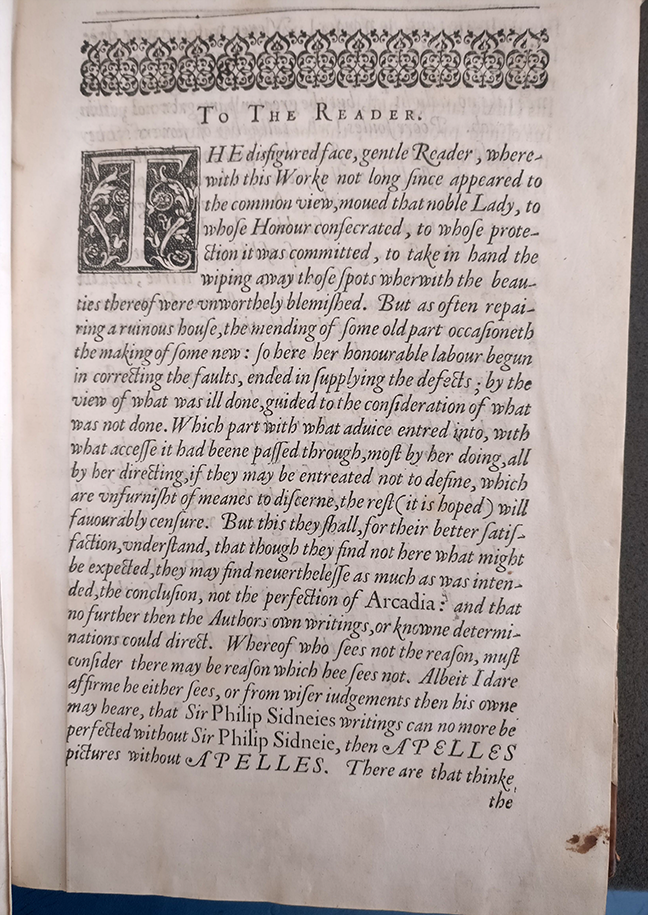

Fig 1. On the left is Erasmus’ letter to John Froben in Thomas More’s De optimo reip. statu, deque noua insula Vtopia… (Basel, 1518), title verso.  Fig 2. Hugh Sandford’s letter ‘To The Reader’, from Philip Sidney, The Countesse of Pembroke’s Arcadia. Written by Sir Philip Sidney Knight, (Dublin, 1621).

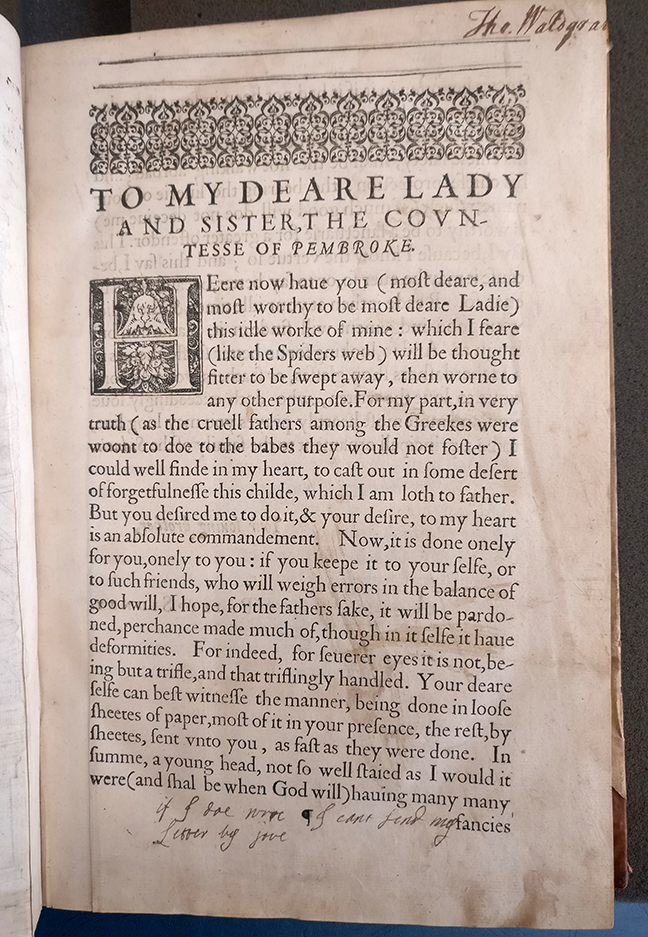

Fig 2. Hugh Sandford’s letter ‘To The Reader’, from Philip Sidney, The Countesse of Pembroke’s Arcadia. Written by Sir Philip Sidney Knight, (Dublin, 1621). Fig 3. ‘To my deare lady and sister’, from Philip Sidney, The Countesse of Pembroke’s Arcadia. Written by Sir Philip Sidney Knight, (Dublin, 1621).

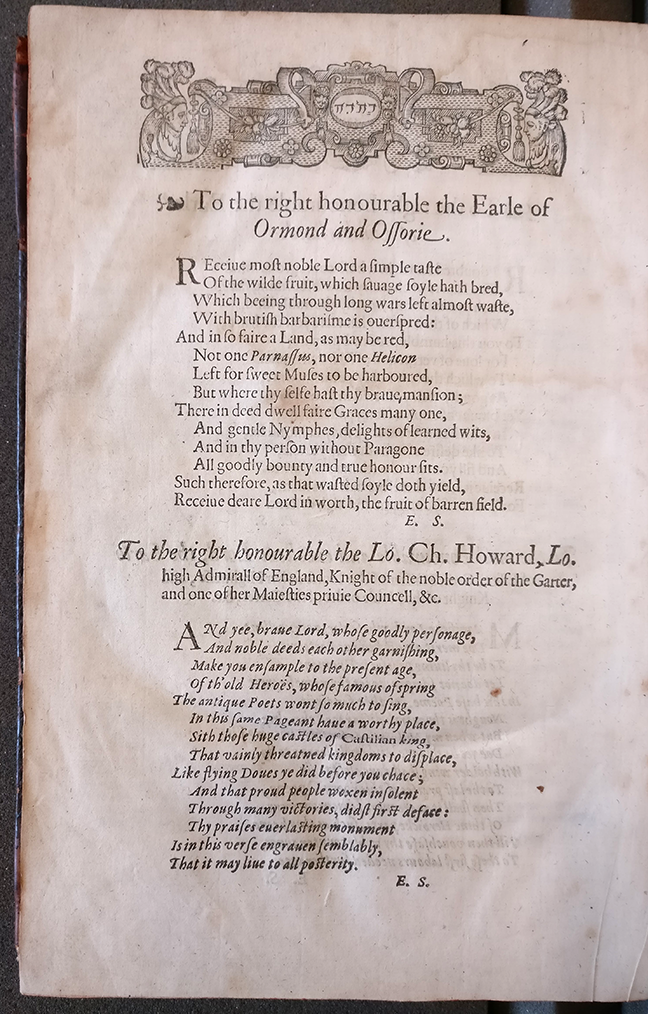

Fig 3. ‘To my deare lady and sister’, from Philip Sidney, The Countesse of Pembroke’s Arcadia. Written by Sir Philip Sidney Knight, (Dublin, 1621). Fig 4. Prefatory sonnets from Edmund Spenser, The faerie qveen, (London, 1609).

Fig 4. Prefatory sonnets from Edmund Spenser, The faerie qveen, (London, 1609).