School club activities and sports in Japanese culture

This article discusses the considerable significance that ‘school club activities’ play in Japanese culture.

School Club Activities

With the extremely high percentage of students enrolling in high schools (more than 97 percent in 2010, reported by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan)(1), it can be reasonably assumed that the life of Japanese youth is substantially synonymous for the life of Japanese high and junior high school students: the youth’s life as a student occupies a large part of his/her life. In these circumstances, Japanese manga and anime have put a great emphasis, presumably perplexingly too great for non-Japanese audience, on school activities as their topics, especially those of school sports clubs.

NAKAZAWA Atsushi enumerates five inexplicable things about the Japanese school activities system:(1)they are organized on a tremendous scale that cannot be observed in other countries, in spite of the fact that (2) they are extracurricular activities and not obligatory; and (3) they are not student-led activities but teacher/school-led, while (4) they are managed at the great expense of schools and, more importantly, of teachers involved; therefore (5) there have been attempts to transfer the responsibility to local communities, but in vain(2). It is a result of the complicated history of Japanese educational system after WWII. According to Nakazawa, the history of Japanese school (sports) club activities was that of amalgamation of, in short, democratism/egalitarianism and elitism/control-oriented education(3). In other words, extracurricular (especially sports) activities have been formally imposed upon students to nurture a liberal, fair spirit of sportsmanship in youth on one hand, and to control their ethics and lives in group (i.e., social) activities on the other. These apparently contradictory goals, interestingly, have served to provide a suitable stage for fierce competitions by good and earnest young students in Japanese juvenile narratives.

Sports Manga and the Battle Narrative

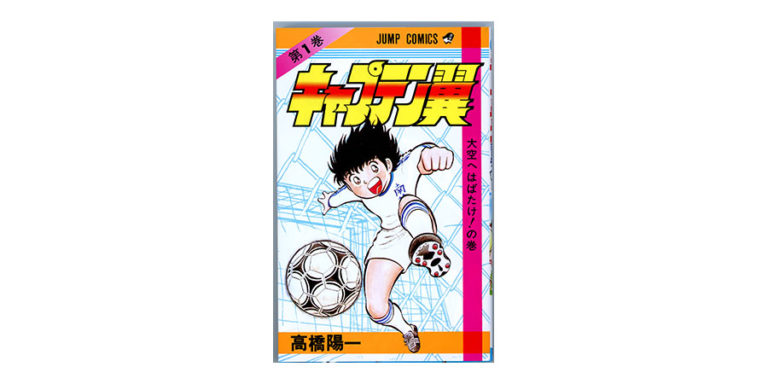

This cultural soil has furnished other types of school club activities with opportunities to be featured in battle-narrative style stories. An epochal work for Japanese society was TAKAHASHI Yoichi’s Captain Tsubasa (or Flash Kicker, 1981-88 in Weekly Shonen Jump), which not only has left an unforgettable mark in the history of sports manga but also greatly helped football gain recognition among Japanese children and allegedly formed a basis for the establishment of the Japanese professional football league in 1991 [fig.1].

Fig.1. Captain Tsubasa, vol.1, cover page, by TAKAHASHI Yoichi, Shueisha 1989

Fig.1. Captain Tsubasa, vol.1, cover page, by TAKAHASHI Yoichi, Shueisha 1989

A football genius, Ozora Tsubasa moves to Nankatsu City and joins the football team of Nankatsu Elementary School to meet a series of formidable opponents and rivals. Though the stage is set in the world of elementary school clubs in the 1980s, the overall system is apparently taken from the Koshien narratives. It is interesting, however, that Captain Tsubasa, as ‘the’ predecessor of the football manga, utilizes some unrealistic superplays to entertain the target readers as did early baseball manga.

Another genius can be found in KONOMI Takeshi’s Tennis-no Oji-sama (Prince of Tennis, 1999-2008 in Weekly Shonen Jump and a new series 2009 to present in Jump Square). The protagonist, Echizen Ryoma, who has proven his abilities by winning junior championships in the US, comes back to Japan to join Seishun Junior High School tennis club and aims for the national championship with his teammates[fig.2]. Significantly, for our purpose, the games described in the work are exclusively those of team competition: each player plays as a member of the school he/she belongs to.

Fig.2. Tennis-no Oji-sama, vol.1, cover page, by KONOMI Takeshi, Shueisha 2000

Fig.2. Tennis-no Oji-sama, vol.1, cover page, by KONOMI Takeshi, Shueisha 2000

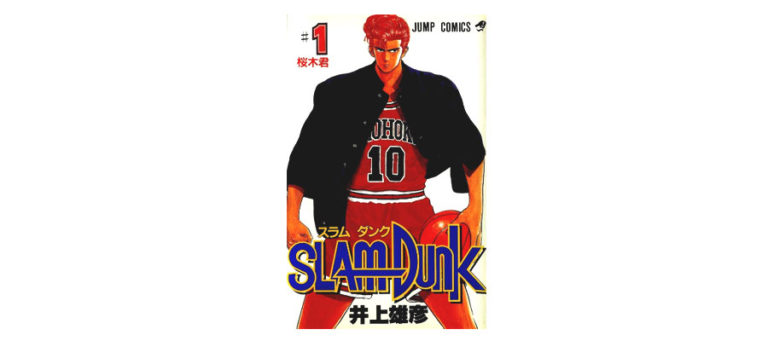

On the basketball court, INOUE Takehiko’s Slam Dunk would be one of the most popular examples[fig.3]. Sakuragi Hanamichi, a red-headed rowdy student, is unexpectedly recruited to the basketball club of Shohoku High School as a sheer beginner. A naturally-gifted athlete, Hanamichi becomes a main member of the team aiming for the high school championship.

Fig.3. Hanamichi in a basketball uniform wearing a school uniform over it. Slam Dunk, vol.1, cover page, by INOUE Takehiko, Shueisha 1991

Fig.3. Hanamichi in a basketball uniform wearing a school uniform over it. Slam Dunk, vol.1, cover page, by INOUE Takehiko, Shueisha 1991

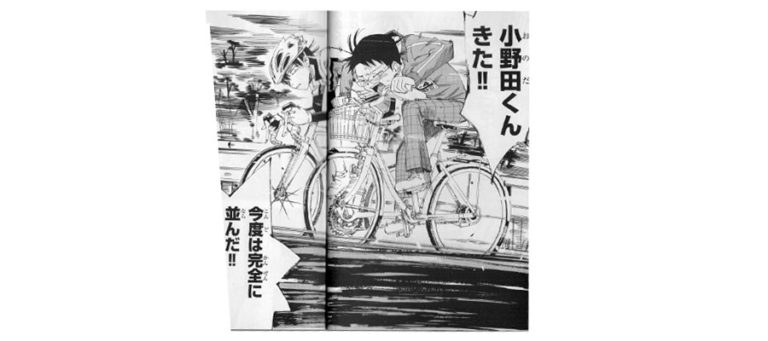

In the same vein, Onoda Sakamichi in Yowamushi Pedal (Cowardly Cyclists, 2008 to present in Weekly Shonen Champion) by WATANABE Wataru has, though an otaku himself, developed a hidden ability as a competent cyclist by often cycling 45 kilometers to Akihabara, and finds himself[fig.4] joining Sohoku High’s bicycle racing club.

Fig.4. Sakamichi in his school gym wear competing with a racing club member. Yowamushi Pedal, vol.2, pp18-19, by WATANABE Wataru, Akita-shoten 2008

Fig.4. Sakamichi in his school gym wear competing with a racing club member. Yowamushi Pedal, vol.2, pp18-19, by WATANABE Wataru, Akita-shoten 2008

Not such a beginner as Hanamichi and Sakamichi, Hinata Shoyo in Haikyu!! (Volleyball!!, 2012 to present in Weekly Shonen Jump) by FURUDATE Haruichi is still not a volleyball expert when he becomes a member of Karasuno High School Volleyball Club. Also short in height, however, he is gifted with considerable physical abilities to compensate disadvantages in technique and in experience[fig.5].

Fig.5. Shoyo spiking the ball tossed by his colleague. © Haikyu!!, vol.2, pp12-13, by FURUDATE Haruichi, Shueisha 2012

Fig.5. Shoyo spiking the ball tossed by his colleague. © Haikyu!!, vol.2, pp12-13, by FURUDATE Haruichi, Shueisha 2012

The protagonists of the above three works become players in sports clubs of their respective schools, thus entering upon the battle arena specifically prepared for high school students. At the same time, we have to pay a special notice to the fact that they are given (physical) advantages beforehand originated from their personal habits. In a sense, they are provided by providence, or the authors, with supportive devices that enable them to be and remain heroes of the stories.

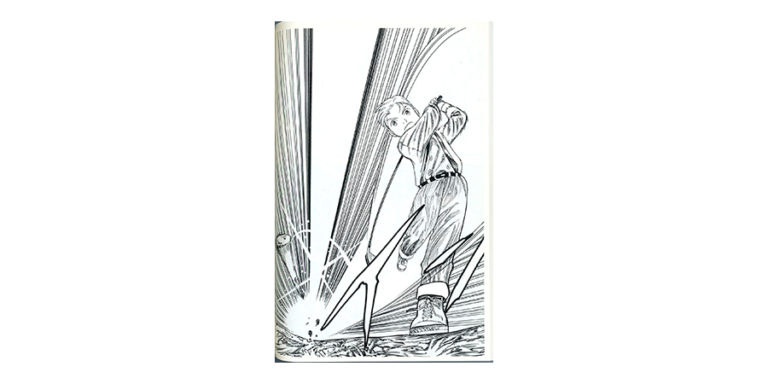

This formula is also applicable to Gawain Nanaumi in Rising Impact (1998-2002 in Weekly Shonen Jump) by SUZUKI Nakaba[fig.6]. A 10-year old pupil of Camelot School, famous for its golf players, Gawain proves himself to be competitive enough thanks to his genius as well as his early childhood spent in the mountainous area of Fukushima Prefecture, in which he cultivated his physical strength.

Fig.6. Rising Impact, vol.1, p50, by © SUZUKI Nakaba, Shueisha 2007

Fig.6. Rising Impact, vol.1, p50, by © SUZUKI Nakaba, Shueisha 2007

The mixture of ‘power-boosting devices’ and the ‘school-club structure’ seen in these works would make us aware of the physicality of the activities they are dealing with. Athletic sports, even of student level, necessarily require of their participants a certain degree of physical strength or abilities on one hand. On the other hand, the poetics of battle narrative forbids the heroes to be ordinary people in a real sense, and demands some means to compensate the seeming lack of talents.

Non-physical Competitions

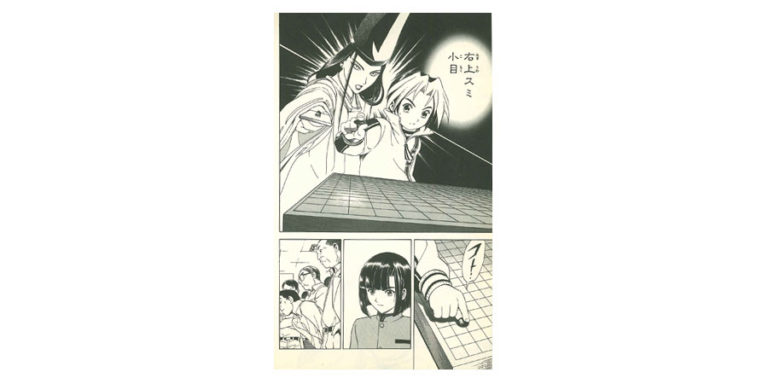

In non-physical kinds of sports, however, this limitation can be much more easily breached, as, in theory, the younger is capable of surpassing their elders mentally and intellectually. This is more obvious on the surface of the board of go, a traditional far-eastern board game with black and white pieces of stone, where there are strict rules binding the players regardless of their age or sex. HOTTA Yumi and OBATA Takeshi’s Hikaru-no Go (Hikaru’s Go, 1999-2003 in Weekly Shonen Jump) has supplied the protagonist Shindo Hikaru with a true ‘genius’, someone who gives instructions to the person he/she haunts: a prodigious go player of the 10th (or 11th) century, Fujiwara-no Sai[fig.7]. By thus visualizing the ‘genius’ separate from the boy, the work discloses the structure of boys’ battle narrative.

Fig.7. Hikaru-no Go, vol.1, p136, by © HOTTA Yumi and OBATA Takeshi, Shueisha 1999

Fig.7. Hikaru-no Go, vol.1, p136, by © HOTTA Yumi and OBATA Takeshi, Shueisha 1999

In Yu-Gi-Oh! (Game King!, 1996-2004 in Weekly Shonen Jump) by TAKAHASHI Kazuki[fig.8], the protagonist Yugi is forced to beat successive opponents, in various kinds of non-athletic games in the early stage and in the Duel Monsters card game in the latter episodes. Even here, Yugi is equipped with a genius by awakening his other, dark self during playing card games.

Fig.8. Yu-Gi-Oh!, vol.10, cover page, by TAKAHASHI Kazuki, Shueisha 1998

Fig.8. Yu-Gi-Oh!, vol.10, cover page, by TAKAHASHI Kazuki, Shueisha 1998

When the match is judged by some connoisseurs, the story becomes calmer and more realistic, while leaving room for the younger to accomplish remarkable achievements. The MasterChef-like competition is introduced in the classic Mister Ajikko (1986-90 in Weekly Shonen Magazine) by TERASAWA Daisuke[fig.9], in which Ajiyoshi Yoichi, a 14-year-old boy, helps his mother to manage a small restaurant after the death of his father who was a renowned cook. He, with his talent in cooking and inexhaustible culinary ideas, participates in the Taste Emperor’s Grand Prix competitions with a variety of rival chefs, being judged usually by the Taste Emperor Murata Genjiro.

Fig.9. Mister Ajikko, vol.19, cover page, by TERASAWA Daisuke, Kodansha-Mangabunko 1990

Fig.9. Mister Ajikko, vol.19, cover page, by TERASAWA Daisuke, Kodansha-Mangabunko 1990

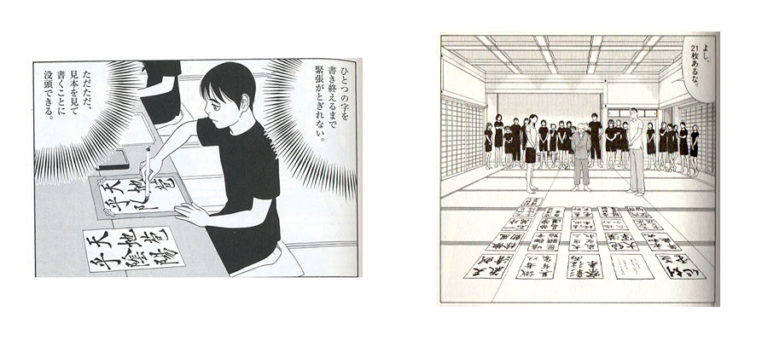

And this competitive framework is found in a more unexpected quarter of Japanese calligraphy. Tomehane! (Full Stop and Upward Turn, 2007-08 in Weekly Young Sunday and 2008-15 in Big Comic Spirits)[fig.10] mainly describes the high school life of boys and girls devoted to Japanese calligraphy club activities, but every now and then the story is coloured by private and public competitions of calligraphy[fig.11]. In this story, the protagonist Oe Yukari, though naturally dexterous in handling things, has little experience in the art, but with earnest training, he develops his skills and becomes evaluated highly by connoisseurs.

Fig.10. Tomehane!, vol.3, p103, by KAWAI Katsutoshi, Shogakkan 2008 Fig.11. Tomehane!, vol.3, p121, by KAWAI Katsutoshi, Shogakkan 2008

Fig.10. Tomehane!, vol.3, p103, by KAWAI Katsutoshi, Shogakkan 2008 Fig.11. Tomehane!, vol.3, p121, by KAWAI Katsutoshi, Shogakkan 2008

The list of works here briefly surveyed delineates, we should notice, an established formula for enabling the youthful protagonist to remain a hero without unrealistic devices like ninjutsu or magic. By limiting the arena exclusively for students or by dealing with games with strict rules which any participants are required to observe, the audience is allowed to enjoy the sincere struggles of the youth with the sense of a certain degree of realism.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free