Kawaii-ness: How It Has Changed Throughout the Years

Let’s take a look at Kawaii-ness in some shōjo manga, then think about Kawaii-ness in the 21st Century.

Chibi-neko of The Star of Cottonland

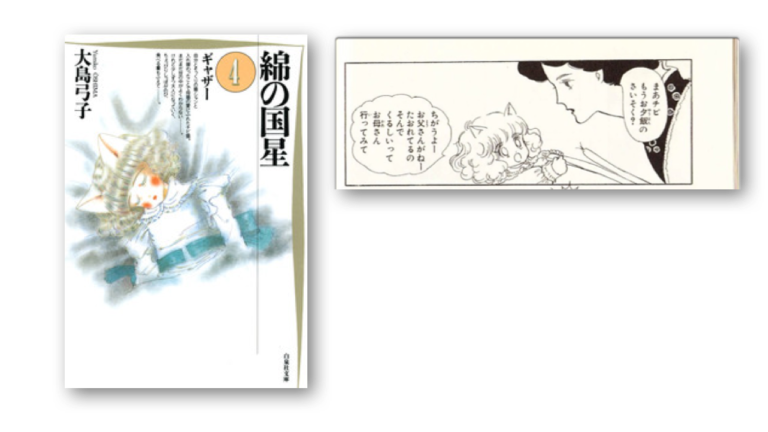

A few years after Kitty’s debut, Yumiko Oshima, a shōjo manga writer famous for her philosophical stories with girlie illustrations, started a serialized comic called Wata no Kuni Hoshi, or The Star of Cottonland (1978-87)(1). Its protagonist and narrator is an abandoned two-month-old kitten, saved by the Suwano family. The kitten, named Chibi-neko, perceives herself to be semi-human, and represents herself as a small girl with cat ears. Chibi-neko somehow believes that she will grow up to be a human being.

Fig. 1. The Star of Cottonland (綿の国星 – Wata no Kuni Hoshi), vol.1, coverpage, vol.2, p. 12, by Yumiko Oshima, 1978-1987 on “LaLa”, Hakusensha

Fig. 1. The Star of Cottonland (綿の国星 – Wata no Kuni Hoshi), vol.1, coverpage, vol.2, p. 12, by Yumiko Oshima, 1978-1987 on “LaLa”, Hakusensha

Chibi-neko, a beautiful white cat—like Hello Kitty—appears in a white dress with a white frill apron. She has blue eyes and fluffy curled hair. She is innocent, ignorant, and needs the protection provided by the Suwano family [fig.1].

Concurrently, her innocence provides her with opportunities to spread happiness and sympathize with others, while learning about the workings of the world. Chibi-neko, however, is an eternal child, because she is never going to be an adult or, in other words, a human being. In this sense, Chibi-neko reflects the emotional aspects of girls having some anxiety about their own identity. However, according to her, she never derives an answer because “When I try to think of one thing, my mind strays away from it. It is because the outside scenery changes day by day.” Chibi-neko does not recognize the stream of time, for she is in the eternal present. This is the transitory characteristic of Kawaii, and girls who are destined to grow up long for this immaturity.

Shōjo manga writers born in 1949

Yumiko Oshima is one of the manga creators categorized as 24-nen-gumi, or “Year 24 group.” Year 24 group refers to Shōjo manga writers born in the 24th year of Showa period, 1949, and whose achievements as shōjo manga writers established the basic format and grammar of this genre. One of the characteristics of their revolutionary poetics in shōjo manga is that the protagonists’ monologue or inner confession about their anxiety (it is similar to the stream of consciousness of modernist novels). According to Eiji Okuda, the root of their anxiety may be traced back to the female liberation from the role of “mother” during the democratization of Japan after World War II. Women were freed from the traditional and oppressive roles imposed on them, and yet the new direction for females was still to be determined. Chibi-neko in The Star of Cottonland, an embodiment of Kawaii-ness, clearly differentiates the sphere of children and youth from that of adults. Hello Kitty, a deadpan Kawaii cat who receives all the affection from girls, offers a relationship based on amae, allowing girls to have time and space to be themselves when surrounded by them.

Kawaii-ness in Cats

Cats possess an elegant independence and adamant disobedience, and yet they keep relationships with people through occasional expressions of a wheedling attitude, thus attracting cat lovers. If independence and dependence coexist, without contradiction, they are probably a perfect representation of Kawaii-ness for girls during the 1970s crystallizing the cultural imagery of cats.

Kowaii vs Kawaii

Cats are probably the most fascinating Kawaii creature because of their kaleidoscopic characteristics. The 1990s witnessed a curious phenomenon, which was the birth of Kowaii cats. “Kowai” means “scary” in Japanese. Kowaii is a newly coined term to express fear or dread in Kawaii objects. You will understand the nuance of Kowaii when you see this illustration by Nekojiru(2), which appeared in 1990 [fig.2]. The protagonists of this story are cat siblings, Nyako and Nyatta. Their father is an unemployed alcoholic, and the mother manages to feed the family. Interestingly, Japan enjoyed the bubble economy when this manga first appeared in a legendary underground manga magazine, Garo.

Fig. 2. Cat Soup (ねこぢるうどん – Nekojiru Udon), (vol.1), p. 9, by Nekojiru, 1990, Garo, Seirindo

Fig. 2. Cat Soup (ねこぢるうどん – Nekojiru Udon), (vol.1), p. 9, by Nekojiru, 1990, Garo, Seirindo

Nekojiru Udon evokes a nostalgic feeling, reminiscent of the time when Japan was still a poor country. The past represented in this manga is reflected in the present with an impalpable uncanny atmosphere, which is described in the cruelty of supposedly innocent and cute kittens. Nyako and Nyatta are, in one sense, victims of child abuse, but they are not helpless kids. They show their cruelty and violence toward their pet dog, small insects, or elderly cats.

Muteness of Kawaii objects

When Yasashisa (kindness in Japanesee) disappeared, Kawaii revealed its uncanny aspects that nobody could control. Emily Raine introduces Sianne Ngai’s discussion on “cuteness,” stating that “cuteness suggests infancy and a certain helplessness” which prompts “sadistic desires for mastery” (203). Here I would like to ask whose desire this is, and who wants to control or to be controlled. Similar to Hello Kitty and other beloved stuffed animals, Kawaii things do not talk, and we love them all the more because of that. The muteness and silence of Kawaii objects enable us to identify ourselves with them, as Christie Yano suggests.

However, we are always apprehensive of the fact that we never know what these mute objects really think, since they do not speak. Nyako and Nyatta are certainly helpless infants, but they do not hesitate to be brutal and cruel to others. We project ourselves onto Kawaii objects, but they may not be so easily controlled. They will stimulate our sadistic desires, but perhaps they are the ones to possess such desires. The fact that Kowaii cats Nyako and Nyatta actually talk, albeit awkwardly, debunks the uncanny in Kawaii objects, through the disguise of a cat—a creature that we are never able to understand in spite of our intimacy. They will not let us have a mutual relationship based on Amae, but instead, they reflect the ugliness and cruelty in ourselves.

Cute Cruelty in Tamala 2010

In the 21st Century, another cute cat reveals cute cruelty. Tamala 2010: A Punkcat in Space[fig.3](3) produced by a group of artists called Tree of Life (t.o.l) was released in 2002.

Fig. 3. Tamala 2010: A Punk cat in Scape, Kinetique inc.,2002 DVD is available at Amazon

Fig. 3. Tamala 2010: A Punk cat in Scape, Kinetique inc.,2002 DVD is available at Amazon

Let’s take a look at the trailer (on YouTube) for the animation. Set in future Tokyo, Tamala, a motherless kitten, departs from earth to search for her mother cat who is allegedly living on the Planet Orion. However, before reaching the final destination, her spaceship makes an emergency landing on Planet Q, where she meets a handsome cat named Michelangelo. Emily Raine states that Tamala is a caricature of Hello Kitty, but it seems to me that she is a descendant of Nyako and Nyatta, who never disguise their cruelty. The public security of Planet Q has deteriorated because of political instability, but Tamala is afraid of nothing. She blatantly shows herself off in a club, dancing fiercely, which eventually attracts Kentauros, a brutal dog cosplaying as a police officer. She is assaulted by the dog, and her headless body is found by Michelangelo, who flees immediately. However, after a while, Tamala comes back to life, and appears in various commercials for every commodity supplied by a huge conglomerate, Catty & Co.

Kawaii-ness in the 21st Century

This animation reveals that our desire for cute objects is closely related to capitalist, materialistic society. Tamala is indeed an innocent kitten, but she never offers Yasashisa (gentleness) to the audience. She is a selfish cat who cares about nothing but her own desire. Nevertheless, she becomes a desired object by showing herself in every commercial of the huge company, Catty & Co. Concurrently, she is the one who captivates us in the commodity society. Thus cruelty in Kawaii-ness ultimately governs us, erasing the “heterogenous ties of a community based on ideals of spontaneous cooperation, mutual affection, . . .” as Emily Raine suggests (198). Tamala, in her monosyllabic talk, repeats the following phrase: “Wait a little longer.” The seducing attitude of the cat is extremely controlling. TAMALA 2010, by disclosing cruelty, baldness, perversity, and eroticism in Kawaii objects, forces us to redefine Kawaii-ness in the 21st Century.

Your Thoughts?

How would you define “amae” relationship in your cultural context? Do you find similar dependent relationships in your own society or in your own experiences? How do you feel about “kawaii” when you see that someone is depending on somebody?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free