Japanese subculture – Eternal girlhood

In Dissecting Subculture Myths (Reference-3) (Sabukaruchaa Shinwa Kaitai) (1993) by Shinji Miyadai, Hideki Ishihara and Meiko Ōtsuka, girls’ manga are divided into several categories: “popular fiction girls’ manga,” in which heroines have experiences readers dream about but are unlikely to actually have, allowing them to experience these things by proxy; “autobiographical/quasi-literary girls’ manga”, which interprets reality and is typified by otometic (or “assertively girlish”) manga; and “pure Western-European literary girls’ manga”, by creators such as Moto Hagio.

The year 1973 saw the appearance of the otometic style, a revolutionary development in the history of girls’ manga. This model incorporated , and marked the beginning of “relational” girls’ manga. It was represented by the group of creators that included A-ko Mutsu, Yumiko Tabuchi, Hideko Tachikake, and (early in her career) Mariko Iwadate, and it can be broadly divided into two types, which we will refer to as “hyper-positive” stories and “complex” stories. In the former, it’s said that “‘The World’ is kind,” and that’s why city mailboxes are red and telephone poles are tall, etc. In the latter, “I’m clumsy and unattractive, but he says he likes me ‘just the way I am.’” In both, the issue is, not experiencing improbable situations by proxy, but how to interpret a real-life and the world that surrounds her. It presents a “relational” model which can accommodate “me”.

For example, let’s take a look at Mariko Iwadate’s Fairy Tale for Two (Futari no Douwa) (1976)(1). The protagonist is Shinobu, an extremely shy girl with a weak constitution. Her mother has died, and she lives with her father, who’s a bit of a worrier. Shinobu Hoshikawa is slow and klutzy, no matter what she does, but she’s honest and kind. The story begins in junior high when she reunites with Takashi Sugawara, a boy she idolized in elementary school. Shinobu is too embarrassed to tell anyone about her feelings, and when a misunderstanding occurs between her and Takashi, she isn’t even able to clear it up. After that, Takashi transfers to another school, and the two of them are separated. However, Shinobu continues to think only of Takashi. In the end, the pair is finally united as high school students, several years after they first met in elementary school. For her part, Shinobu thought, “I was content just to watch him,” but in the end, it’s revealed that they both liked each other all along. In this story, it’s possible to detect the message, “I loved you the whole time,” or in other words, “I like you just the way you are.” [Fig.1]

Fig. 1. Futari no Dowa, vol.2, p132, by ©Mariko Iwadate, 1976 (Shinobu, suffering from finding out that Takashi might have a girlfriend, which later turns out to be her misunderstanding)

Fig. 1. Futari no Dowa, vol.2, p132, by ©Mariko Iwadate, 1976 (Shinobu, suffering from finding out that Takashi might have a girlfriend, which later turns out to be her misunderstanding)

Osamu Hashimoto discusses the model otometic manga creator, A-ko Mutsu. Hashimoto contends that girls feel they need affirmation that someone likes them just the way they are from another person (in this case, a boy), and that, in order to get them to say this, they create flaws – such as being shy, or short, or having lots of freckles – for themselves (Hanasaku Otome no Kinpira Gobo (Reference-2). In short, continuing to dream of having someone say “I like you best that way,” after creating a self that’s full of flaws, is the essence of otometic manga. Considered in combination with Miyadai’s interpretation, one could say that otometic manga flourished in the early 1970s because it provided a model by which, through being aware of reality in a particular way, girls who are living in that reality become able to navigate it more easily.

In that case, what does this “awareness of reality” recognize? Awareness of reality through the heroines of girls’ manga is simply the recognition that one is living in the midst of relationships with other people. That is precisely why there are no heroines like Oscar in The Rose of Versailles (Berusaiyu no Bara) (1972-73)(2), characters who are idolized for embodying proxy experiences. Instead, as in the previously discussed Fairy Tale for Two – or as in the case of Momoko, the heroine of Chime (Chaimu) (1980, also by Mariko Iwadate)(3), who has a complex regarding her older twin sister [fig.2], they see girls who are harboring some kind of complex but must still maintain their relationships with others, and find role models among them that make them think, “This is me!” In other words, the girl readers run simulations of situations they’ll have to live through in their own lives by reading manga.

Fig. 2. Chaimu , p. 204, by ©Mariko Iwadate, 1980 Momoko, who always feels inferior to her elegant and modest sister, goes back to her hometown, suppressing her feeling toward Noboru, whom she secretly loves.

Fig. 2. Chaimu , p. 204, by ©Mariko Iwadate, 1980 Momoko, who always feels inferior to her elegant and modest sister, goes back to her hometown, suppressing her feeling toward Noboru, whom she secretly loves.

For girls who are living in the midst of a web of relationships with others, who are these “others”? With whom do they want relationships, and who do they want to acknowledge them? This is, naturally, the person they like best, and in girls’ manga – in which love is generally heterosexual – it is the boy for whom they have unrequited feelings. These romantic manga, which were generally set in schools, were known as “school dramas,” and they constituted a major trend from the 1970s to the 1980s. In these stories, heroines who were the same age as the readers developed unrequited feelings for boys, as the readers did, and in the end, their earnest feelings were rewarded. It isn’t hard to imagine that such stories resonated with many readers. For example, Chizuru Takahashi’s Quivery Coffee Jelly (Pururun Coohii Zerii) (1977)(4), which ran in the magazine Nakayoshi, is the story of Ryoko, who hasn’t liked coffee jelly since losing her boyfriend to a friend because the taste reminds her of lost love. Ryoko, who has a complex about her beautiful friend, is drawn to Shu, who works at a café. However, she assumes that he, too, likes her friend, and falsely imagines that she’s lost another love. When it becomes clear that Ryoko is the one Shu really likes, she becomes able to eat coffee jelly again [Fig.3].

Fig. 3. Pururun Coffee Jerry, p. 161, by Chizuru Takahashi, 1977, Kodansha Ryoko has been unconfident since her then-boyfriend approached one of her friends. She, however, accepts who she is when Shu finally confesses his love for her.

Fig. 3. Pururun Coffee Jerry, p. 161, by Chizuru Takahashi, 1977, Kodansha Ryoko has been unconfident since her then-boyfriend approached one of her friends. She, however, accepts who she is when Shu finally confesses his love for her.

Note that Yukari Ichijo’s Designer (Dezainaa) (1974)(5) was among the girls’ manga of that era, and that sweeping romantic stories – some of which, like Jun Makimura’s The White Flower of Eryx (Eryukusu no Shiroi Hana)(6), dealt with incestuous relationships – also existed. In the first place, there were some who felt a sense of wrongness about girls’ manga whose framework was “love for love’s sake.” Although this wasn’t a trend that was present in all girls’ manga, at the very least, works belonging to a certain category of such manga reflected girls’ desires and fantasies. Conversely, it seems safe to say that girls who read this sort of manga thought that they needed affirmation from boys and grew as a result, creating a cycle.

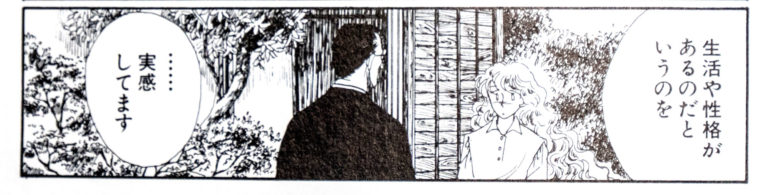

This type of “affirmation received from others” also means noticing the existence of people besides oneself. It is linked to accepting an increase in the space others occupy in one’s world, and it’s possible to see girls’ growth here. For example, let’s take a look at the Sakumi Yoshino work, The Crowd in the Moonlight (Gekka no Ichigun) (1982-1983)(7). Marika, the heroine, is completely reliant on her little brother Jiu, who is both sociable and good in school. The rest of her family is quite capable, and she is the only one who can’t keep up. Possibly due to her intense insecurity regarding this fact, Marika doesn’t know how to deal with others. However, one day, she meets one of Jiu’s friends, a young man named Kemikawa who is intelligent and handsome, but brusque. She subsequently catches glimpses of an unknown world and all sorts of human relationships which she’s never encountered before, and gradually, she changes. As is plainly shown in the scene in which Marika talks with her strict father, who formerly made her uncomfortable[Fig.4], she confesses that she “really understands that other people have their own lives and personalities.” It’s worth noting that the change in Marika’s awareness – the shift from “I’m the only one who’s like this…” to “I’m not the only one who’s like this, am I?” – was brought about by the young man Kemikawa. Knowing oneself is, at the same time, linked to knowing others, and by extension, to being conscious of the reality of the world to which one belongs, and of the world beyond that.

Fig. 4. Gekka no Ichigun by Sakumi Yoshino, 1982-83, Kodansha Marika was not interested in others before she met Kemikawa, through whom she gets to know others, recognizing those people’s lives and personalities.

Fig. 4. Gekka no Ichigun by Sakumi Yoshino, 1982-83, Kodansha Marika was not interested in others before she met Kemikawa, through whom she gets to know others, recognizing those people’s lives and personalities.

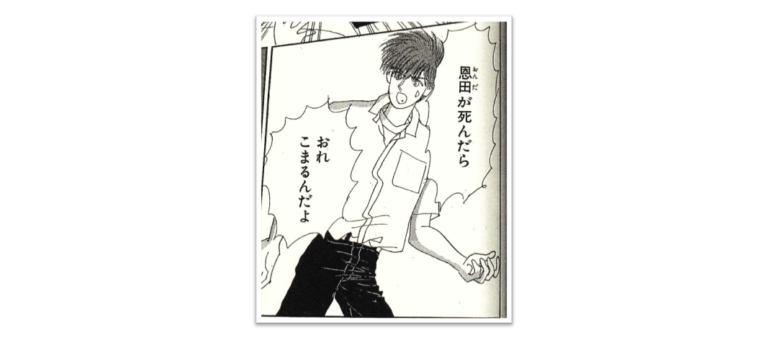

Mariko Iwadate’s You Are the Moon of Third Street (Kimi wa Sanchoume no Tsuki) (1985)(8) features a similar setup. As in The Crowd in the Moonlight, Rutsu Onda is dependent on her capable younger brother, Akira. When her brother gets a girlfriend, Rutsu is pushed to become self-reliant, but then, as if to fill her brother’s place, Hino, a boy who has had feelings for her for a while, appears [Fig.5]. At this point, the boy’s cry of “If you die, Onda, I won’t know what to do” makes her aware of the existence of others.

Fig. 5. Kimi ha Sanchome no Tsuki, p. 81, by ©Mariko Iwadate, 1985 Hino accepts Rutsu, who has quite a few flaws, just like her.

Fig. 5. Kimi ha Sanchome no Tsuki, p. 81, by ©Mariko Iwadate, 1985 Hino accepts Rutsu, who has quite a few flaws, just like her.

Of course, not all girls’ manga stories end happily. For example, take a look at works from the early ‘80s by A-ko Mutsu, known as the originator of otometic manga. The Days of Rose and Rose (Bara to Bara no Hibi)(9), published in 1985, begins when two sisters, Asae and Riri, fall in love at the same time. As a matter of fact, they’ve fallen in love with the same boy, but they don’t know it. Christmas is coming, and Asae and Riri both resolve to give a present to the boy they like and confess their feelings to him. However, the boy already has a girlfriend. At this point, it isn’t possible to get words of outside affirmation (in other words, the phrase “I love you just the way you are”) from the boy. However, a more positive self-affirmation is demonstrated: That of becoming aware of oneself through the existence of others. “This isn’t a sad thing. Maybe it was necessary.” “Yes. It’s as though we’ve gotten one step closer to someone who’s waiting for us, somewhere.” Whether the love is unrequited or reciprocated, these words affirm growth achieved through romantic experience. Or again, in Fumiko Tanikawa’s Hana Ichi Monme (Hana Ichimonme) (1989)(10), the protagonist Sakurako is in love with her biological older brother, Kou. Naturally, incestuous feelings go unrewarded, but she says to herself “I really can’t manage it right now, but… I’m sure… Someday, I want to be able to think, ‘I’m glad I’m your little sister, Kou,’ from the bottom of my heart,” and finds positive meaning in the very act of loving someone. In another Tanikawa work, Feeling like Full Moon (Kimochi Mangetsu)(11), the heroine, Michiru, realizes that her feelings for the older student she liked were only an infatuation. At the end of the story, she thinks, “Someday, I’ll fall in love with someone. Those feelings will grow and become a full moon that never wanes.” This thought can be interpreted to mean a shift toward love as a step that’s necessary for personal growth, instead of love itself, or rather, that she sees it as a necessary element for growth. Accordingly, she’s telling the readers that, even if they’re disappointed in love, it isn’t anything to worry about.

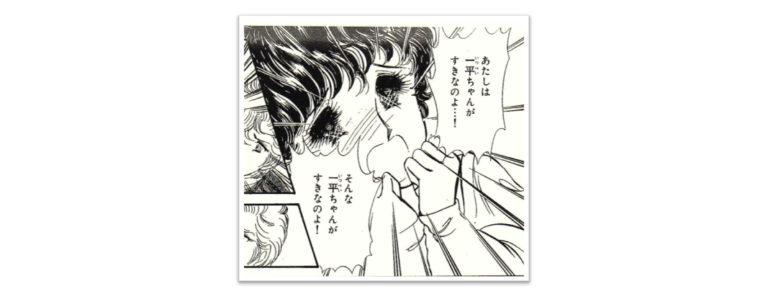

One other common romantic pattern in girls’ manga is “falling for an odd boy.” This can be said to be self-affirmation that comes from understanding what’s good about that particular person when other people don’t, based on the idea that “I see something in the person that no on else does.” This isn’t about appearances being deceiving. “The only person who understands me” has transitioned to “the person only I can understand,” and “liking him just the way he is” is the flip side of “being liked just the way I am.” In Let Me Call You My Hero (Yobasete MY Hiiroo) (1984)(12) by Yū Asagiri, currently active as a boys’ love novelist, Mayu is a girl who’s both beautiful and intelligent and attends a highly academic school. She’s true to her feelings, not for her upperclassman Ono – who is handsome, attends the same high school and gets excellent grades – but for Ippei, her drab childhood friend. However, here, it’s Ippei who worries that he may not be a good match for Mayu. Still, at the school festival, Mayu yells “I like you the way you are, Ippei!” from the stage. She has the courage to actively publicize the fact that she likes a boy like him [fig.6].

Fig. 6. Yobasete My Hero, vol.2, p. 326, by Yu Asagiri, 1984, Kodansha Mayu, “the Miss of Kitazono High school,” cares for Ippei, her childhood friend who is dull and unappealing to most of the girls. Mayu knows that she is the only one who can recognize his tenderness.

Fig. 6. Yobasete My Hero, vol.2, p. 326, by Yu Asagiri, 1984, Kodansha Mayu, “the Miss of Kitazono High school,” cares for Ippei, her childhood friend who is dull and unappealing to most of the girls. Mayu knows that she is the only one who can recognize his tenderness.

As discussed above, girls’ manga as a model for relationships exists, and its most important aspect is affirmation of self received from others. Of course, ultimately having your feelings for the person you love reciprocated is a happy ending that belongs only to the realm of manga, and readers are aware that these stories couldn’t happen in real life. Even so, the hope that “It just might happen tomorrow” has a hint of reality to it. Since the girl readers’ happy endings are constantly delayed this way, girls’ manga must be mass-produced. In other words, the interval while the happy ending is being postponed is, for otometic girls, happiness.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free