Edo-period Writers: Re-interpreting the Japanese classics

Share this step

The basis of the social order was the bakuhan system, which placed the lords of the local domains (han) under the authority of the central government (the bakufu), but left them considerable discretion in exercising power. Stability brought economic growth, which was further aided by the growth of large cities and the booming of trade. Rapid population growth also meant that more people than ever before were now involved in producing and consuming culture (broadly defined as to include knowledge, education, and leisure).

High and Low Culture

We can distinguish two main dimensions of culture: traditional culture, which had been passed down for centuries and was universally regarded as highbrow and prestigious, and the new mass culture, which was popular and ephemeral, and enjoyed popularity for a short while only to disappear soon after. The difference between the two can be compared to the difference between classical music and pop music today. Edo-period people called the first, “high” type of culture “ga” (refined, high) and the second type “zoku” (popular, low).

Just as sometimes popular musicians borrow elements from classical music and classical musicians perform popular pieces, the worlds of ga and zoku were not rigidly separated but often crossed ways and interacted with each other giving rise to various hybrid forms.

A parody of the Pillow Book

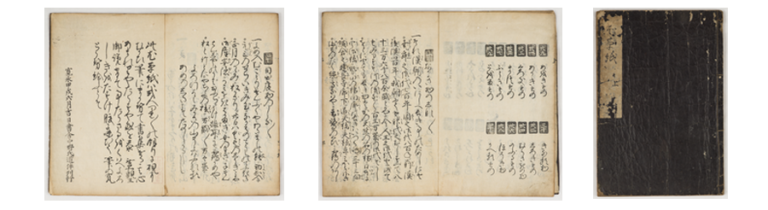

The Mottomo no sōshi (Fig.1) (first half of the 17th century) was one of the many parodies of the classics that were popular at the time. What we see here is a reprint published two years after the first 1632 edition.

Fig.1. Mottomo no sōshi

Fig.1. Mottomo no sōshi

Click to take a closer look

The Mottomo no sōshi 尤之双紙 is a parody of the Makura no sōshi 枕草子 (The Pillow Book), an early 11th century miscellany by the court lady known as Sei Shōnagon, a lady in waiting of empress Teishi (977-1001) and a consort of Emperor Ichijō (980-1011).

“Mottomo” means “reasonable” or ”convincing” in Japanese but more importantly the title is meant to be a pun on the original title Makura no sōshi. The similarities between the two even extend to the characters in the title, “Mottomo” 尤 being almost identical to the right part of the character “Makura” 枕 (pillow).

The Pillow Book is one of the foundational texts of the Japanese courtly aesthetics. It is particularly famous for its lists of items, such as “Beautiful things”, “Auspicious Things”, etc. The Mottomo no sōshi mimics this structure by presenting lists of “Long things”, “Short things,” but the content of the lists could not be further removed from the elegant world of the Heian aristocracy. The items listed are unfailingly coarse things from the everyday life of the commoners, and anybody familiar with the refined world of the original cannot help but laugh at the contrast. Thus, Edo parodies relied on the reader’s knowledge of the classics to entertain. The first printed (movable-type) edition of the Makura no sōshi appeared in the Keichō era (1596-1615), and the Mottomo no sōshi a mere 20 to 30 years later. The making of these parodies shows just how broad the readership of the classics had become.

The spread of high culture to a mass audience

If parodies brought the classics down to the world of zoku, reverence for them remained high, among ever widening segments of society. Contradictory though it may seem, this sentiment of “reverence” for the classics was the main reason of their spread to a mass audience.

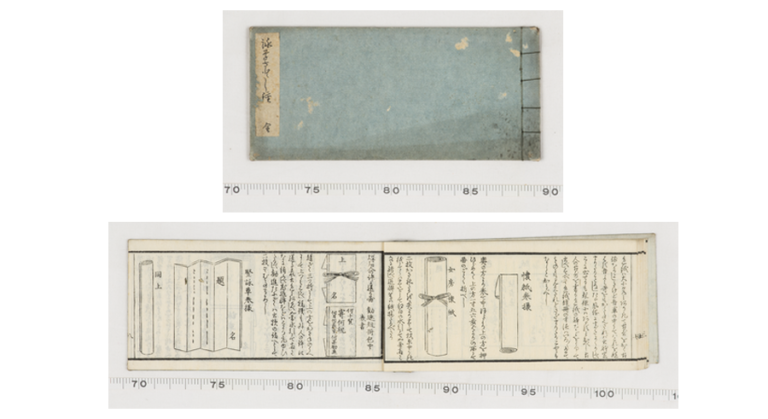

Fig.2. Eisōsatoshigusa (A manual for poetry composition), yokohon, 1853

Fig.2. Eisōsatoshigusa (A manual for poetry composition), yokohon, 1853

Click to take a closer look

The Eisōsatoshigusa (Fig.2) , dating from the late Edo period, is a beginner’s guide to waka composition. A courtly genre, waka was a symbol of high culture throughout the pre-modern period. However, during the Edo period there was a significant increase in the number of people who composed waka in both cities and rural areas. The publication of a large number of introductory manuals such as this one reflects this increase in demand.

The Tale of Genji in the Edo Period

The early-11th century Tale of Genji (Genjimonogatari) is probably the most famous of all the Japanese classics. Like the Makura no sōshi, the Genji was first published in printed form around 1600, but its influence on Edo literature and culture was profound. Here I would like to mention two works in particular that show the level of interest that the Genji generated.

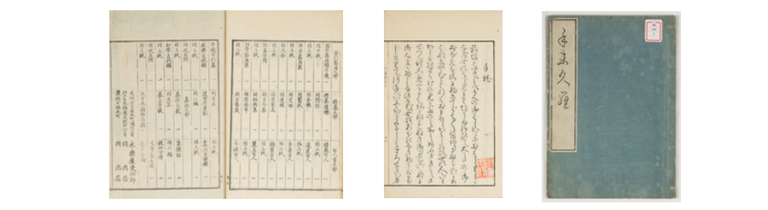

The first is the Tamakura (Fig.3) (Hand as Pillow, ca. 1750s) by Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801), a prominent scholar with a lifelong interest in the Genji.

Fig. 3. Tamakura, Motoori Norinaga, 1792 edition.

Fig. 3. Tamakura, Motoori Norinaga, 1792 edition.

Click to take a closer look

It is a sort of appendix to the Genji that presents scenes that do not appear in the original tale. It is written in a language that replicates in every detail Murasaki Shikibu’s 11th century idiom and only an erudite scholar could have written it.

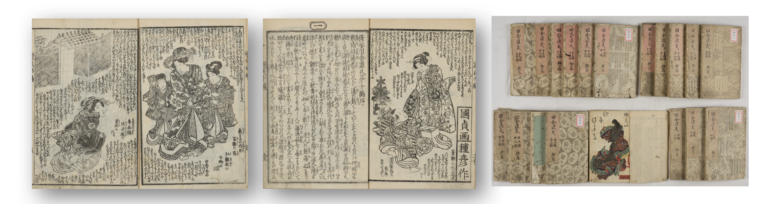

The second work is the Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji (Fig.4), which was serialized between 1829 and 1842 by Ryūtei Tanehiko (1783-1842).

Fig. 4. Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji (A Fake Murasaki’s Country Genji)

Fig. 4. Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji (A Fake Murasaki’s Country Genji)

Left: preface of book 10, Center: Beginning of the text

Click to take a closer look

This is a humorous retelling of the Genji set in the warrior-dominated world of Muromachi Japan. However, both the narrative and the illustrations incorporate elements from contemporary Edo culture and society. It was wildly popular, especially among women. In the preface to the tenth installment in the series, which was published in 1833, the author shares his struggle to find a suitable style to write the story. He records the advice of two friends, one young and one old. Whereas the old man apparently advised Tanehiko to adhere as closely as possible to the source text, the youth argued that as young women were unlikely to be captivated by such a text,the new version should incorporate elements from kabukidrama and freely adapt the original text to provide a more entertaining reading experience. Tanehiko concludes by saying that although initially he had followed the young friend’s advice,for the past year or so he had been following the old man’s advice and was still now wondering whose advice to follow. In other words, throughout the writing of Inaka Genji, Tanehiko kept wavering between the two approaches.

To sum up, during the Edo period, the courtly, traditionally prestigious world of “ga” not only spread to a wider audience through printed books, but it also became the basis for countless parodies and creative adaptations. This rather free, playful attitude to the past and the classics is still very much alive in contemporary Japanese culture.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free