Japanese Literature: The Power of Books in the Edo Period

![Kasen kashū [Poetry Collections of the Immortal Poets] Kasen kashū [Poetry Collections of the Immortal Poets] (with marginalia by Keichū, Shiigamoto bunko)](https://ugc.futurelearn.com/uploads/images/46/96/46963b4d-f3f5-44a9-88b0-b2730a490315.png)

Share this step

During the Edo period, not only were the Japanese classics published in printed form for the first time, but there was also an unprecedented eagerness to study them and understand them in greater depth than ever before.

The classics were studied in the medieval period too, for example by waka poets who admired the Kokinshū and the Tale of Genji, but it was primarily a small number of court aristocrats who were involved in such study. By contrast, and thanks to the spread of printed books, in the Edo period people from a diverse range of social backgrounds devoted themselves to scholarship.

Keichū

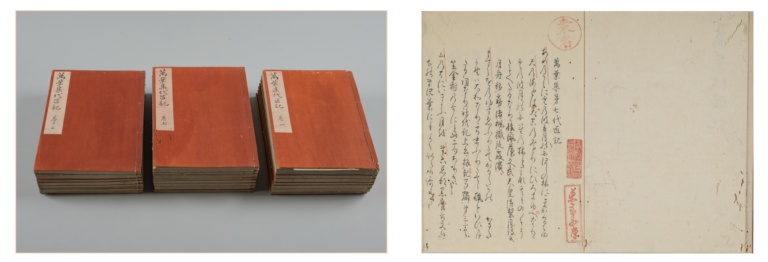

One of the great scholars of the period was Keichū (1640-1701), a Buddhist priest of the Shingon sect. In many ways, his scholarly approach was perfectly suited to the age. Keichū’s magnum opus is the Man’yōshū daishōki (Fig.1), a commentary to the Nara-period poetry collection Man’yōshū (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves, mid-8th c.).

Fig.1. Man’yōshū daishōki (A Stand-in’s Account of the Man’yōshū ), Keichū,

Fig.1. Man’yōshū daishōki (A Stand-in’s Account of the Man’yōshū ), Keichū,

Click to take a closer look

Keichū’s aim in writing this work was to reconstruct as closely as possible the original meaning of the text by looking at a wide range of contemporary and near-contemporary sources. Within the work, Keichū discusses the basic principles of his approach to the study of the past, which can be summarized as follows:

- Reconstruct the contemporary meaning of the work and avoid at all costs any interference from the modern reader’s expectations and beliefs.

- Make use only of sources from the same time period or thereabouts.

- Do not take for granted the theories contained in later commentaries, including traditionally authoritative ones, because they may not be accurate or not apply directly to the age of the Man’yōshū.

Keichū applied these principles not only to the Man’yōshū, but also to the Kokinshū and other important works of the past. Through his method he made a number of important breakthroughs that forever changed the face of scholarship on the classics.

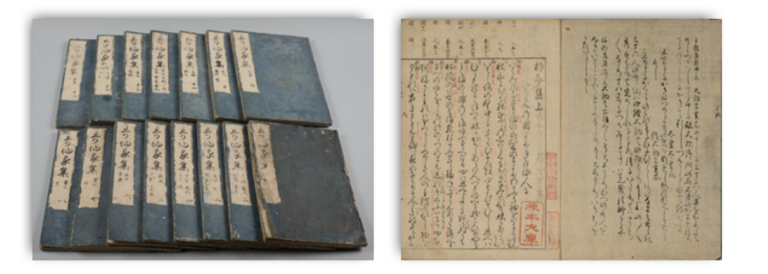

Although Keichū’s method may seem obvious today, no one before him had used such a rigorous philological approach in waka studies. Traditionally, waka scholars studied under a master and the emphasis was on amassing the transmitted teachings of one’s school or “house” (ie) rather than on textual study. Keichū never studied under a specific master, and so was never bound by a master-disciple type of relationship. Even more important was the boom of book publishing, which enabled Keichū to obtain the texts he needed for his research with ease. As sources for his commentary to the Man’yōshū, Keichū names the Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720), the Kaifūsō (Collection of Fond Recollections, 751), the Shoku Nihongi (Later Chronicles of Japan, 797), the Kogo shūi (Gleanings of Ancient Words, 807), the Shinsen Man’yōshū (Newly Edited Man’yōshū, 894), and the Wamyō ruijūshō (Japanese Words by Category, ca. 938), all of which were written between the 8th and 10th centuries, and all of which were available in print when Keichū wrote Man’yō daishōki in 1683. None of them had ever been printed prior to the late 17th century, so it can be said that Keichū’s text-based scholarship would have been impossible in earlier periods. That Keichū’s approach relied heavily on printed editions of the texts he studied can be seen from the many notes and comments that he personally wrote on his own printed editions of the classics. Keio University Library owns one such book (Fig.2).

Fig.2. Kasen kashū

Fig.2. Kasen kashū

Click to take a closer look

Motoori Norinaga

After Keichū, many scholars of so-called Nativist Studies (kokugaku or wagaku) adopted his philological method and produced groundbreaking studies and reinterpretations of the Japanese classics. Kada no Azumamaro(1669-1736), Kamo no Mabuchi (1697-1769), and Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801) are some notable examples. Motoori Norinaga in particular was the one who made the most of the new opportunities provided by publishing.

Norinaga came from a family of merchants from Matsusaka in Ise province. Having realized early that trade was not his vocation, he established himself as a physician and at the same time began to study the classics, especially the Nara-period Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters, 710), to the study of which he made an immense contribution. His Ashiwake obune (A Small Boat Through the Reeds) takes the form of a dialogue and contains the following exchange:

常縁何故に古今伝授と云ふことを作りたるや。答へて云はく。本朝に昔は、書物に板本と云ふことはなかりしなり。板本はいと近き世になりてのことなり。昔はみな写本にて行はれしなり。しかるに足利将軍家の末に至り、天下大きに乱れて世の中騒がしかりしゆゑに、昔の書物ども多く失せて世に稀なりしに、この常縁多く古書を所持して、世になき書物どももありしなり。その中に定家卿の顕注密勘などその外もあるをみて、それに本づきてさまざまのことを作り加へて、古今伝授と云へるなり。その比は世に書物少くして、古書をみること稀なれば、常縁が云ふことを珍らしく思ひ、まことに貫之より相伝のむねと心得たるなり。今の世には古書もあまねく世に広まりて、古へを考ふるに暗きことなければ、かの作りごとも書物をみれば弁へらるることなれども、そこへ心を付けてみる人少くして、なほかの偽物に欺かれてゐるなり。[English translation] “Why did Tōno Tsunenori [late-medieval warlord and poet] create the “Secret Transmission of the Kokinshū” (Kokin denju)?” “Here is the answer: at the time, the Japanese classics had never been published. It is only in recent times that they have been published. Up to that point, they were only available as manuscripts. With the turmoil of the late Muromachi period, a lot of books were lost to fire. Tōno Tsunenori had a rich collection of books, which included works unknown to the public, such as Kokinshū commentaries like Teika’s Kenchū mikkan. He used these works to fabricate a set of theories which were known as the Kokin denju. At the time there were few books and ancient works were especially rare, so Tsunenori’s theories sounded authoritative and were believed to reflect the teachings of Kokinshū compiler Ki no Tsurayuki himself. But today the classics are readily available in printed version and it is very easy to research the past if one wishes to do so. It is obvious to anyone who reads the classics that these so-called “teachings” are nothing but later fabrications. And yet, somehow, few seem to care much about this and the “Kokin denju” is still considered authoritative.

It is hard to believe that Norinaga was only in his mid-twenties when he wrote this book. He shows a clear grasp of the limitations of earlier waka scholarship and of the power of books to overcome them. Norinaga was perhaps even more aware than Keichū of the power of the printed word. To begin with, he actively sought to publish his works. Before him, it was uncommon for scholars to publish their works during their lifetime. Keichū only published two of his works, so did Kamo no Mabuchi, and Kada no Azumamaro published none at all. By contrast, Norinaga published a staggering total of about 30 works during his lifetime.

Besides Norinaga’s personal interest in publishing, his prolific output shows just how popular the study of antiquity was in the second half of the 18th century. The reputation of Keichū, Mabuchi, and Azumamaro’s scholarship grew after their death, and their works were published regularly between the late 18th century and the first half of the 19th century.

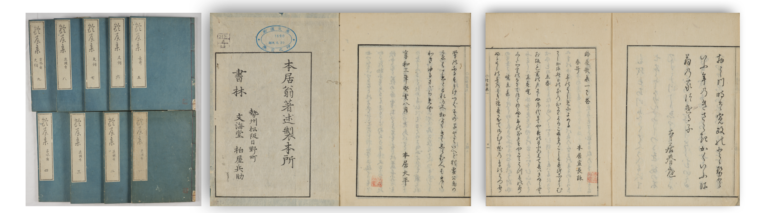

Fig.3. Suzunoya-shū, Motoori Norinaga

Fig.3. Suzunoya-shū, Motoori Norinaga

Click to take a closer look

Norinaga’s successful publishing career, which was aided by his numerous disciples, must be seen as part of this larger phenomenon (Fig.3). His publications earned him even more disciples, as many were drawn to study with him by the ideas expressed in his books. He kept a list of the students regularly studying at his school and the total is in excess of 500. Norinaga’s students formed a nationwide network and his published works provided the connecting tissue among them.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free