Movable Type Printing and Woodblock Printing in Japan

Share this step

In this article, we will examine the characteristics of movable type printing using an edition of the Heike monogatari (Tale of the Heike).We will then discuss the differences between movable type printing and woodblock printing using the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan) as an example.

Editions of the Heike monogatari (Tale of the Heike)

The Tale of the Heike deals with the rise and fall of the Taira General Taira no Kiyomori (1118-1181) against the backdrop of the wars between the Taira and Minamoto clans in the late 12th century. It is the most representative work in the war tales ( gunki monogatari ) genre. It is thought to have first been written in the first half of the 13th century, and enjoyed wide circulation, both as a written work, and as a performance text chanted by blind minstrels known as biwa hōshi . However, it was never printed in the medieval period and it was not until the beginning of the early-modern period that the first printed editions appeared. Of all movable type books, the Heike is the most frequently published work of the movable type era. The scholar Kawase Kazuma has identified ten different editions based on a study of the type used. Keio University Library owns seven different items, from the following five editions:

- A. Shimomura-bon (Shimomura-text)

- B. Jūichigyō hiragana bon (11-line Hiragana text), published by Kawaramachi Niemon

- C. Fukun katakana-bon (Annotated Katakana text)

- D. Nakanoin-bon (Nakanoin text). (Two versions, one with editorial note and one without; 1 fascicle from book 12)

- E. Jūnigyō hiragana-bon (12-line hiragana text); two versions, with the type set differently.

A. Shimomura-text

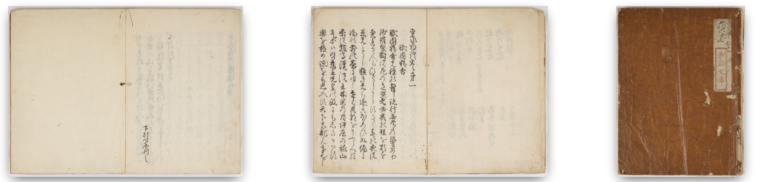

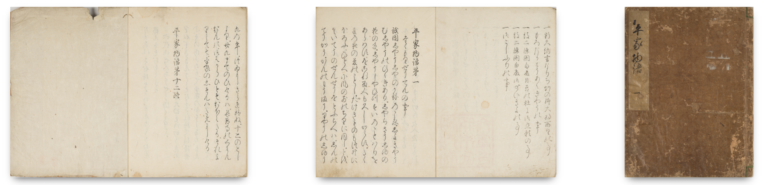

Fig.1. Heike Monogatari (Tale of the Heike), Shimomura-bon, Colophon (left) of Vol.12, Opening section (center) and Cover (right) of Vol.1,

Fig.1. Heike Monogatari (Tale of the Heike), Shimomura-bon, Colophon (left) of Vol.12, Opening section (center) and Cover (right) of Vol.1,

Click to take a closer look

The colophon of Text A (Fig.1) says that it was published by a Shimomura Tokifusa, but nothing is known about him. The year of publication is not noted, but the book is thought to date from the Keichō era (1596-1615). The book also bears the seal of the archive of the wealthy late-Edo merchant Ozu Hisatari (1804-1858), the Seisō Bunko, so we know that, for a time, it was in his collection.

B. 11-line Hiragana text, published by Kawaramachi Niemon

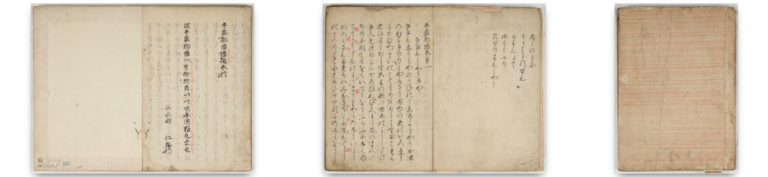

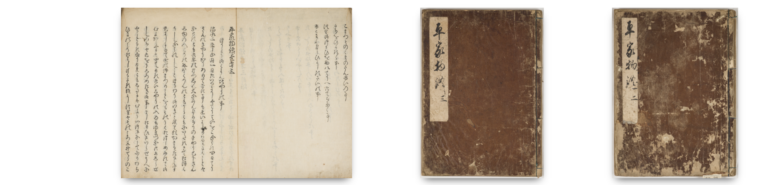

Fig.2. Heike Monogatari Jūichigyō hiragana bon,Colophon of vol.6 (left), Opening section of vol.1 (center) and Cover of vol.1 (right),

Fig.2. Heike Monogatari Jūichigyō hiragana bon,Colophon of vol.6 (left), Opening section of vol.1 (center) and Cover of vol.1 (right),

Click to take a closer look

The colophon of text B (Fig.2) says that the text was approved by performers of the Ichikata School of Heike performance, and published by a man called Niemon who resided in the Kawaramachi area of Kyoto. It is thought to have been printed in the Gen’na era (1615-1624).

C. Annotated Katakana text

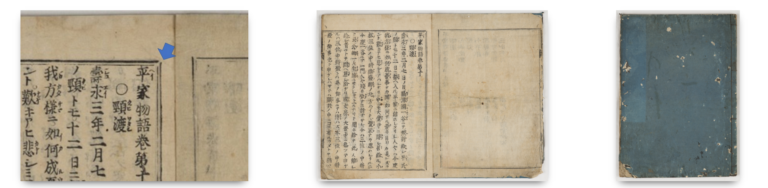

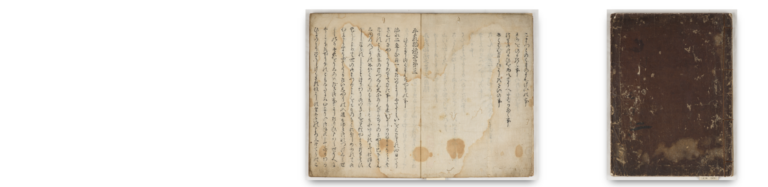

Fig.3. Heike Monogatari, Fukun Katakana -bon, Gap in the outer border (left), Opening section (center) and Cover (right),

Fig.3. Heike Monogatari, Fukun Katakana -bon, Gap in the outer border (left), Opening section (center) and Cover (right),

Click to take a closer look

Item C (Fig.3) is thought to date from the Kan’ei era (1624-1645) and it is the only edition to use a mixture of katakana and kanji (all other editions use hiragana and kanji ). It is also the only edition to enclose the text in an outer border (kyōkaku, Korean kwangg-wak), a typical feature of books published in China and Korea. The horizontal and vertical lines of the border were printed using different pieces, so sometimes there is a gap between the two, as item C here shows. The gap in the outer border is one of the ways that we can tell a typeset book from a block-printed one, keeping in mind that only a small number of typeset books feature the border.

D. Nakanoin text

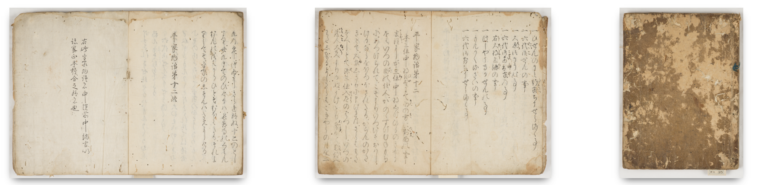

Fig.4. Heike Monogatari, Nakanoin-bon with editorial note, Colophon with editorial note (left), Opening section (center) and Cover (right),

Fig.4. Heike Monogatari, Nakanoin-bon with editorial note, Colophon with editorial note (left), Opening section (center) and Cover (right),

Click to take a closer look

Fig.5. Heike Monogatari, Nakanoin-bon without editorial note, Colophon without editorial note (left), Opening section (center) and Cover (right),

Fig.5. Heike Monogatari, Nakanoin-bon without editorial note, Colophon without editorial note (left), Opening section (center) and Cover (right),

Click to take a closer look

The colophon of Item D (Fig.4, Fig.5)states that the text was carefully edited by Nakanoin Michikatsu (1558-1610), a courtier and well-known literary expert. Keio Library owns two copies of the book, one of which does not bear the colophon. They are both thought to have been printed in the Keichō era (1596-1615).

E. 12-line hiragana text

Fig.6. Heike Monogatari, Jūnigyō hiragana-bon (1), Opening section of book3 (left), Cover of book3 (center) and Cover of book2 (right),

Fig.6. Heike Monogatari, Jūnigyō hiragana-bon (1), Opening section of book3 (left), Cover of book3 (center) and Cover of book2 (right),

Click to take a close look

Fig.7. Heike Monogatari, Jūnigyō hiragana-bon (2),Opening section of book3 (left), and Cover page (right),

Fig.7. Heike Monogatari, Jūnigyō hiragana-bon (2),Opening section of book3 (left), and Cover page (right),

Click to take a close look

Finally, item E was printed in the Kan’ei era (1624-1645) using the same text as the Nakanoin edition, but the type that was used is smaller. Again, Keio Library owns two copies (Fig.6, Fig.7) that differ slightly in the arrangement of the type.

Unfortunately, there is much we still do not know about who published these books, and when. However, these multiple editions of the same work suggest that, one, there was a large number of people involved in typographic printing, and two, that these publishers had enough enthusiasm to enlist the help of learned aristocrats and actual performers to produce editions of the finest quality.

Editions of the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720)

We have already noted that “old” movable type printing was in vogue for about 50 years between the late 16th and the mid-17th centuries. After this time, there was a return to the earlier method, woodblock printing, with some adjustments from earlier times.

- A. Nihon shoki , “old” movable type edition, 2 vols.

- B. Nihon shoki , woodblock imprint

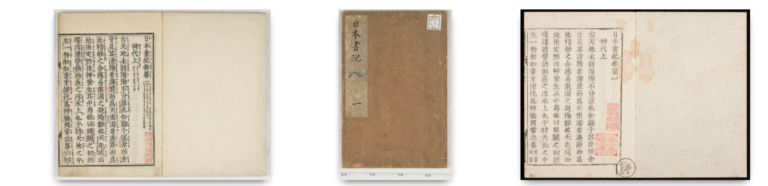

(Right) Fig.8. A. Nihon Shoki, “old” movable type edition, Opening section

(Right) Fig.8. A. Nihon Shoki, “old” movable type edition, Opening section

Click to take a close look

(Left and Center) Fig.9. B. Nihon Shoki, woodblock imprint, Opening section and Cover page

Click to take a closer look

Item A (Fig.8, A) is a movable type edition of the Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720) published in 1610. Item B (Fig.9, B) is a woodblock edition published in the Kan’ei era (1624-1645) based on the earlier movable type edition.

The Kan’ei era is when woodblock reprints of existing movable type editions began to be produced in large numbers, whereas movable type printing gradually declined. If we compare the two books, we can see one of the reasons. Whereas item A only gives the main text, item B also includes reading marks to facilitate reading and notes. In terms of ease of reading, edition B is far superior. The problem was technical: in order to provide reading glosses in a typeset text one must either make a new set of small type for the glosses or create a type with both the larger characters for the main body of the text and the smaller type for the glosses. This is not only very expensive, it also constrains the process of setting the type to a virtually unmanageable degree. By contrast, in woodblock printing everything is carved onto a single block of wood, so it is easy to add notation and glosses. A few movable type books with notation marks were made (for example, item C of Heike Monogatari in the list above), but it never truly caught on, likely for financial reasons.

Summary

With movable type printing, once you have the basic type, you can combine it in different ways to produce a wide variety of books. Or rather you have to print a wide range of different books to cover the costs of producing the type. This trend to publish more and more titles became more evident as time passed and the number of publishers increased, and it continued even after the decline of movable type and the return to block printing. In other words, it is in the early-modern period that Japanese publishing truly became a commercial enterprise with many publishers marketing widely a large number of titles.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free