What is the Shōsōin?

Share this step

The ancient books we look at pique our curiosity and inspire us to learn more about the history of books in East Asia. These texts have traveled down to us today because they were but one aspect of a rich and complex book culture. Many of them were jealously guarded in libraries and archives, the oldest and most venerable of which is the Shōsōin.

The word shōsōin initially referred to the storehouse of any important establishment, and many such archives were built during the Nara period (710-784), both within temples and at government facilities. However, very few of these archives survive today, so today the name Shōsōin refers specifically to the library of the Tōdaiiji temple in Nara. The Shōsōin houses an impressive collection of Nara-period texts that were collected by the government and the imperial family in the 8th century.

Today the Shōsōin is under governmental jurisdiction. The Shōsōin Office of the Imperial Household Agency is in charge of conserving the building and supervising the collection. The library has been under governmental protection since 1875 (Meiji 8) because of the many priceless items it includes, starting with texts made under emperor Shōmu and empress Kōmyō in the 8th century.

It was Shōmu who built the Tōdaiji temple in 728 as one of the temples officially in charge of praying for the safety and prosperity of the state. During the Nara period, Buddhism was formally sponsored by the state and, in addition to religious functions, it performed various state functions.

The Shōsōin collection includes items that were added to it after it was nationalized in the early 20th century. These include a large quantity of religious texts formerly stored in the “Shōgo” (Holy Words) archive of the Sonshōin temple. Of special significance among them are several complete copies of the Buddhist tripitaka (the complete Buddhist textual canon) produced under consort Kōmyō (701-760), Empress Shōtoku (r. 764-770), and Emperor Kōnin (r. 770-781) respectively.

The building of the Shōsōin is an example of the azekura (log-storehouse) architectural style. For centuries, its raised-floor chambers have protected its precious content from extreme temperatures and humidity. Although today the collection has been relocated to a new, purpose-built facility, it is still organized according to the old denomination system based on the buildings of the original site (e.g. “Northern Storehouse” [Kita-kura], “Central Storehouse” [Naka-kura], “Southern Storehouse” [Minami-kura], and so on).

Among the many important pieces in the collection is a set of items previously owned by the imperial family which were donated to the Tōdaiji in different batches by Empress Kōmyō after Emperor Shōmu’s death in 756. They include wooden altars, paintings, and textiles from China and the Korean kingdom of Silla, as well as items that reached Japan through the trade routes of Central Asia, including the Persian-style lute (biwa) shown in figure 1.

Fig. 1. Five-stringed lute, Shōsōin (From the “Shōsōin” exhibition catalog, Heisei 3)

Fig. 1. Five-stringed lute, Shōsōin (From the “Shōsōin” exhibition catalog, Heisei 3)

Click to take a closer look

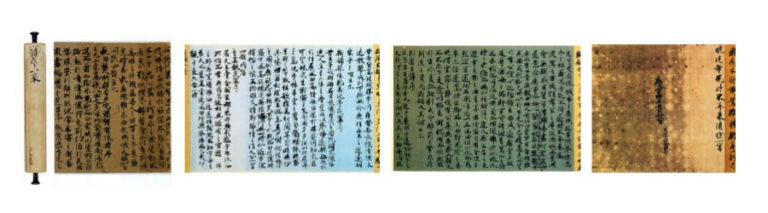

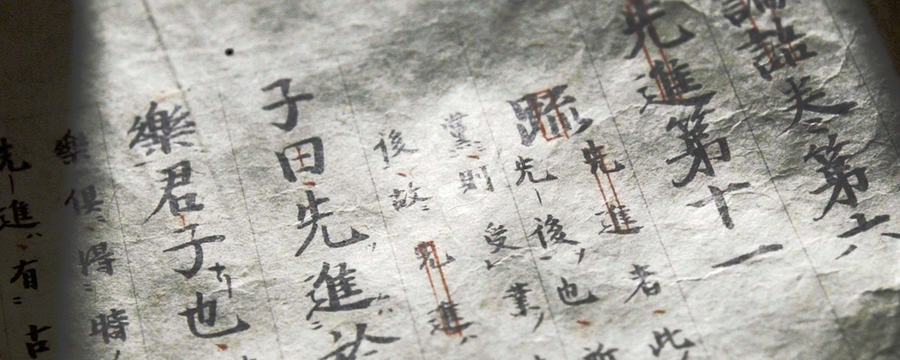

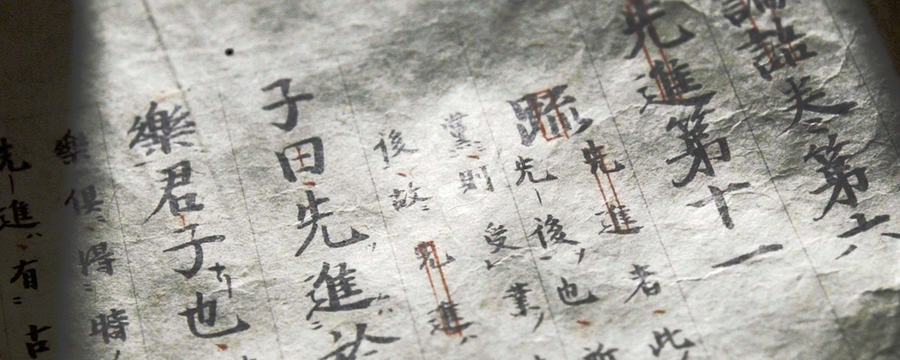

The so-called “Northern Storehouse” houses some texts, including a holograph collection of Emperor Shōmu’s writings and a copy of the Yueyilun (J. Gakkiron, Essay on General Yue Yi) in the hand of Empress Kōmyō. These two items show the level of sophistication that Japanese textual culture had reached by the mid-Nara period. The ‘Central Storehouse’ contains an early-8th century (pre-707) selection of fine writing (including a ‘Poetry Preface’ ([fig. 2] by the early Tang literatus Wang Bo (649-676)) that was used as a calligraphy copybook and which happens to be among the earliest examples of non-religious texts to have been copied in Japan. The paper is multi-color hemp paper, and the calligraphic styles used are rather distinctive, with examples of the rare “Empress Wu’s characters” (Zetian wenzi, J. Sokuten moji), a new style introduced by the Chinese Empress Wu Zetian (624-705).

Fig. 2. Shijo (Poetry prefaces), Imperial Household Agency, Shōsōin (1-4)

Fig. 2. Shijo (Poetry prefaces), Imperial Household Agency, Shōsōin (1-4)

[left][center left][center right][right]

The ‘Central Storehouse’ also houses a large trove of administrative documents and temple documents relating to the Office of Sutra Copying known collectively as “the Shōsōin documents” (Shōsōin monjo). Since the Office of Sutra Copying was a government-funded office, the documents it produced were regarded as official documents and were stored in the imperial archive. These documents provide much valuable information about the activities of the Office and its connections with the government. Moreover, because they were often written on the back of paper that had been previously used in other offices not related to sutra copying, they are also an invaluable source of information on Nara-period administration as a whole.

The Central and ‘Southern’ Storehouses also contain items relating to the construction of the Tōdaiji temple, as well as banners, garments, and masks (gigakumen) that were used in ceremonies and rituals such as the burial of Empress Shōmu, the eye-opening ceremony (kaigan) of the Great Buddha. Other famous pieces in the collection are a cut-glass bowl and vessels from Persia.

According to documents housed in the Central Storehouse several complete copies of the Buddhist canon were produced under the sponsorship of the Nara court. These were vast editorial enterprises totaling 5,000 volumes in size. One such complete set was formerly stored in the Shōgo archive of the Sonshōin and was later added to the Shōsōin’s collection.

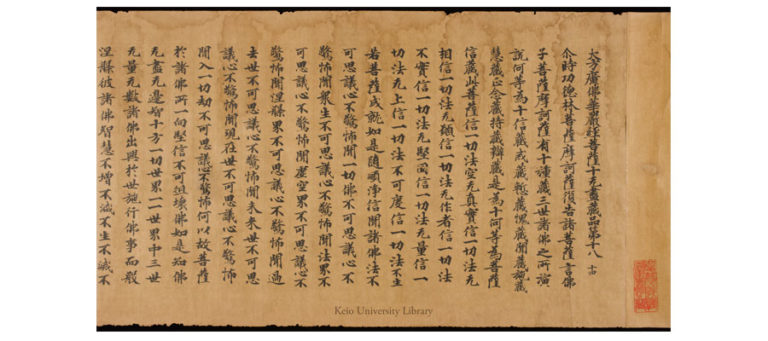

The Shōgozō Tripitaka (this is the name of the set) contains texts produced in the mid-to-late Nara period (740-780), such as the Kōmyō kōgō gogan-kyō (also known as the “May 1st Sutra” [Gogatsu ichinichi-kyō]), which carries a dedication dated 5.1.740, and the Shōtoku tennō chokugan-kyō dating from 768. The Vinaya in Four Parts (Dharmagupta vinaya) that we looked at in Step 2-4 and vol. 14 of the Daihō kōbutsu Kegonkyō [fig. 3] now in Keio University’s library were originally part of this set.

Fig. 3. Daihō kōbutsu kegonkyō

Fig. 3. Daihō kōbutsu kegonkyō

Click to take a closer look

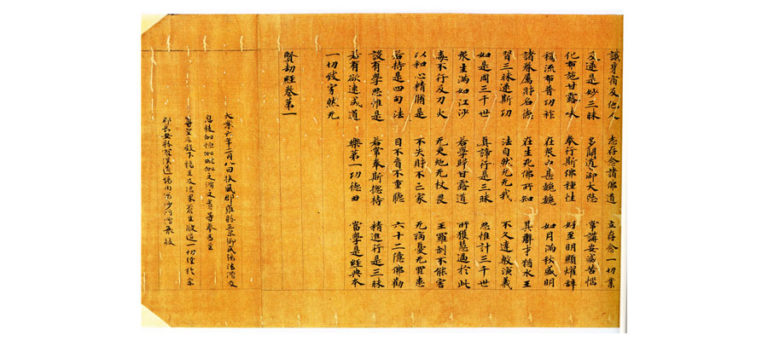

The Shōgozō Tripitaka also includes some Sui and Tang-dynasty Chinese texts that served as sources for the copies. Examples include a 610 copy of the Fortunate Aeon Sutra (Bhadrakalpikasūtra, J. Gengōkyō, 3rd c. C.E.) [fig. 4], and a Tang-dynasty copy of the Four Parts Vinaya. They rival the texts uncovered at Dunhuang as some of the finest Sui and Tang-period texts in existence.

Fig. 4. Gengōkyō, 610 copy, Shōsōin, Shōgo-zō (From the “Shōsōin” exhibition catalog, Heisei 7)

Fig. 4. Gengōkyō, 610 copy, Shōsōin, Shōgo-zō (From the “Shōsōin” exhibition catalog, Heisei 7)

Click to take a closer look

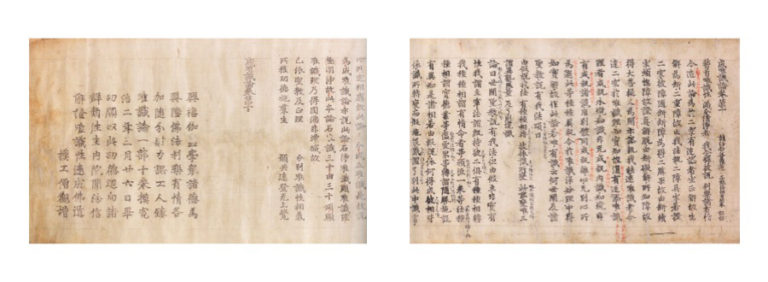

The Shōgozō collection also contains later additions, such as a Heian-period edition of the Discourse on the Perfection of Consciousness-only (Ch. Cheng Weishi Lun; J. Jōyuishikiron) printed in 1088 (Kanji 2) as a “Kasuga-ban” (see Step 1.12) (fig.5), which has the distinction of being the first full-size printed book to be made in Japan.

Fig. 5. Jōyuishikiron (Kasuga-ban), Imperial Household Agency

Fig. 5. Jōyuishikiron (Kasuga-ban), Imperial Household Agency

[Left: 10th scroll] [Right: 1st scroll]

In conclusion, the Shōsōin’s extensive collection of early and medieval Chinese and Japanese texts provides an incredibly vivid picture of the early history of East Asian book culture, and reminds us of the crucial role that Buddhism played in it.

Share this

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free