The Kanazawa Library

Share this step

In this article, we explore the broader cultural context behind the emergence of print culture in Japan by talking about the Kanazawa library (Kanazawa bunko), a historical library established in the 14th century at the very beginning of the transition from traditional manuscript culture to print culture.

The Kanazawa library is one of the most important of the large traditional libraries. Libraries were created by individuals and organizations as information collection facilities. What role did they play in Japanese cultural history?

The Kanazawa library was founded by a group of Kamakura military figures who had broken free from the control of the court with the purpose of studying and learning from the resources amassed by the Kyoto aristocracy. While the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate (military government) by Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-1199) in the late 12th century gave the warrior class actual political power, in the cultural sphere they remained very much dependent on the Kyoto court elite.

The Hōjō family, who took over control of the shogunate from the Minamoto family at the death of Yoritomo, governed by appointing aristocrats from Kyoto as shogun (plenipotentiary commander) and acting as their Regents. However, properly dealing with the new “aristocratic” shogun, especially in matters of ceremonial, required extensive knowledge of court customs and rules.

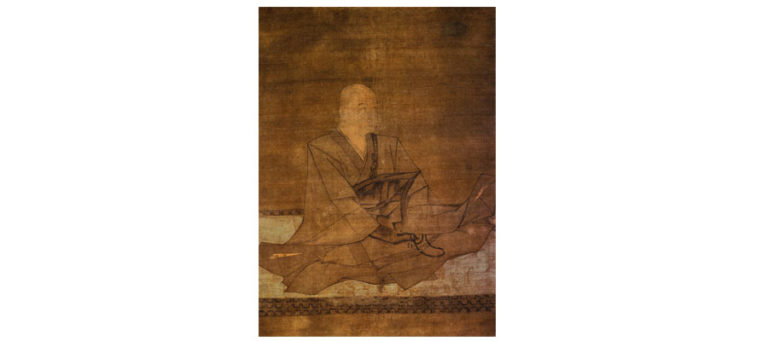

The role of cultural liaison for the shogunate fell on Hōjō Sanetoki (1224-1276) [fig. 1], who served under Regents Tokiyori and Tokimune in the mid-Kamakura period. Sanetoki owned the Mutsura estate in Musashi province (modern Kanazawa ward, Yokohama City), and built his residence there in Kanazawa, so his descendants are known as the Kanazawa-line Hōjō.

Fig. 1. Portrait of Hōjō Sanetoki, Kanagawa Prefectual Kanazawa-Bunko Museum (From the “Buke no koto” exhibition catalog)

Fig. 1. Portrait of Hōjō Sanetoki, Kanagawa Prefectual Kanazawa-Bunko Museum (From the “Buke no koto” exhibition catalog)

Click to take a closer look

Sanetoki was a gifted scholar. In order to familiarize himself with court culture, he studied under Kiyohara no Noritaka, a professor of Confucian Classics. At the same time, he did not neglect Japanese works such as the Honchō zokumonzui (Late Selection of Excellent Writing from Our Country, 12th c.), and also put together a collection of prominent Japanese-language works such as the Kokinwakashū (Collection of Waka Old and New, 905) and the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari, early 11th c.). He gradually specialized in works related to government, which he read in versions annotated by prominent scholars. He also produced his own meticulously annotated copies of these texts.

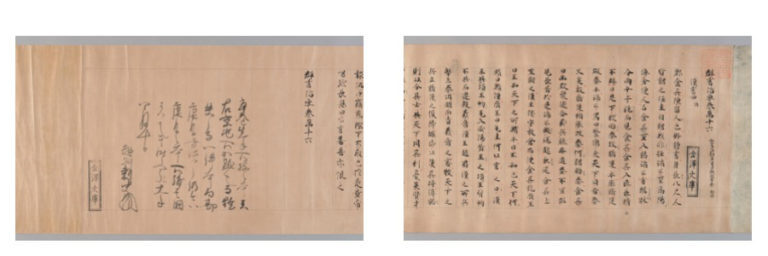

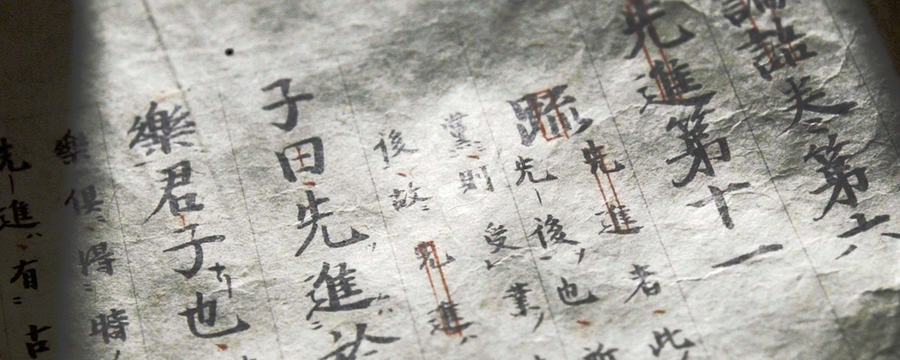

Old Chinese texts preserved in Japan are traditionally known as kyūshōhon (Old Texts). Among those in Sanetoki’s hand that survive are copies the 3rd-century Chunqiu jingchuan jijie (J. Shunjū kyōden shūkai, Spring and Autumn Annals and Zuo Tradition with Collected Commentaries) and of the Tang period political encyclopedia Qunshu zhiyao (J. Gunsho chiyō, Collected Writings on Important Matters of Government) [fig. 2].

Fig. 2. Gunsho chiyō, vol. 16, opening and colophon [left:colophon][right:opening]

Fig. 2. Gunsho chiyō, vol. 16, opening and colophon [left:colophon][right:opening]

As scholarship flourished, archives had to be built to house the ever-growing number of texts. Over time, the Hōjō collection grew into a first-rate library, which would later become known as the “Kanazawa” library. Very few texts dating from the Heian period survive today, but the finest and most ancient ones are often from the collection of the Kanazawa library.

Sanetoki was also a devoted Buddhist. He built an Amida hall in his residence and performed his devotional activities there. Eventually, the hall became the Shōmyōji temple and, with the monk Shinkai as first abbot, it was converted into a Shingon-risshū sect establishment. The Shōmyōji temple was later to play a key role in preserving the library’s collection.

Both Sanetoki’s role within the shogunate and his scholarly activity were continued by his descendants Akitoki, Sadaaki, and Sadayuki. His grandson Sadaaki (1278-1333) even reached the position of Regent, albeit only for a short while. As a result, the library’s collection continued to grow, with Chinese works taking up the lion’s share. Because of his experience as the Rokuhara Tandai (a mix between a local magistrate and an envoy of the shogun to the court) in Kyoto, Sadaaki was able to amass a large quantity of legal texts and manuals of court protocol, such as the Hossō ruirin and the Jichū gun’yō, as well as literary works like Tamakiharu (Fleeting is Life, known also as Kenshun’mon-in chūnagon nikki).

Also noteworthy is the continued influx of printed works from Song China. Newly-collated editions of the Shangshu zhengyi (Correct Meaning of the Classic of Documents) and the Chunqiu jingchuan jijie (Spring and Autumn Classic with Tradition and Collected Commentaries) were published under emperor Xiaozong (r. 1162-1189) and in 1216 (Jiading 9) respectively, and both made their way to Japan during the Kamakura period. Slowly but surely, these Song-era publications reshaped the thinking of Japan’s ruling elite.

The most significant aspect of this influx of texts from Song China was the variety of texts that were brought in. Looking at books formerly in the Kanazawa library, in addition to the classics, one finds encyclopedias, medical treatises, and the collected writings of various Song-period literati.

Traditional “encyclopedias” (ruisho) were actually compendia of excerpts from important texts of the past. They served as primers for the education of future emperors and were made regularly even before the age of print. The expansion of printing during the Song, however, ushered in a new season of thriving of this kind of books. For instance, the 1,000-volume Taiping Yulan (Imperial Reader of the Taiping era), compiled for emperor Taizong, was printed several times during the Song-dynasty alone. The Kanazawa library holds the 1199 edition. With their innovative use of large titles and fonts of different size for different sections, this large late-Song encyclopedic project shows a whole new level of attention to detail in book printing and publishing.

The library also contained medical treatises such as the Waitai miyaofang (Secret Essentials from the Outer Terrace, 8th c.). The diffusion of medicine and medical tracts contributed not only to the growth of publishing but also to enlarge the numbers of those who read and engaged in scholarship. The Tuzhu bencao (Sources of Materia Medica with Illustrations and Annotations), a key text of pharmacy covering remedies of plant, animal, and mineral origins is also among the works in the collection.

Coming to scholarship on the classics, the Song saw the publication of works that gathered multiple commentarial traditions into single works. One example is the Lunyu zhushu (J. Rongo chūryū, Commentaries and Subcommentaries to the Analects). Such works had been made during the age of manuscripts, too, but not as often as during the Song, and the same concept was now applied to a variety of fields.

Another interesting feature of the Kanazawa library is that it contained books printed not only in the Zhejiang area, through which most of the trade with Japan passed, but also in the Sichuan, Zhejiang, and Fujian areas (known as “Shoku” [Ch. Shu] books (Shoku-hon), “Setsu” [Ch. Zhe] books (Seppon), and “Ken” [Ch. Jian] books(Ken-pon), respectively). Simply by browsing through the collection, one can get a sense of just how widely books circulated in China during the Song.

In terms of content, Song-period editions tend to fit into the following four categories: authoritative editions of the classics, large format editions, illustrated editions, collections and series. The collection of the Kanazawa library spans all four fields, thus providing a condensed view of not only medieval Japanese book culture, but of East Asian book culture as a whole. With its unique combination of ancient Chinese manuscripts and Song-dynasty printed books, moreover, the library integrates two modes of accessing texts that were often at odds with one another, providing a faithful picture of medieval Japanese book history and culture.

Whereas Song-dynasty publications had only limited influence on the scholarship produced by the Heian court, the printed texts in the Kanazawa library were the very foundation for the scholarly achievements of warrior-scholars. However, to see printed books make an impact on culture at large, we have to turn to the activity of the Zen temples in Kamakura (see next step).

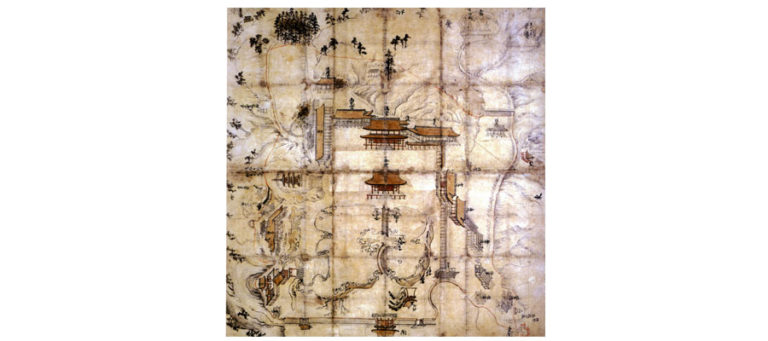

The Shōmyōji temple became an important temple of the Shingon-risshū sect and, after Shinkai, produced great scholars like Ken’na (1261-1338) and Tan’ei (1271-1347). Making good use of their ties with the scholarly centers in Nara, these men succeeded in establishing the Shōmyōji as the main center of Buddhist scholarship in the Kantō area.

Fig. 3. Shōmyōji kekkaizu, Kanagawa Prefectural Kanazawa-Bunko Museum (From the “Buke no koto” exhibition catalog)

Fig. 3. Shōmyōji kekkaizu, Kanagawa Prefectural Kanazawa-Bunko Museum (From the “Buke no koto” exhibition catalog)

Click to take a closer look

The temple’s collection began to take shape with the donation of a complete edition of the tripitaka (published in Fuzhou) and the works brought to Japan by the Japanese monk Enshu studied in Song China. Over time, commentaries and lecture records by local scholars were added to it. Even the sect’s texts secret teachings, its secret rituals and formulas, were eventually committed to writing; together, these writings are known as the Shōgyō (Holy Teachings) .

Thus, as printing and publishing spread from the Nara temples to the Shōmyōji and surrounding temples, printed editions of Buddhist texts became part of the libraries of these establishments alongside handwritten works.

The Shōmyōji temple and the Kanazawa library were originally independent institutions, but after the fall of the Kamakura shogunate in 1333 (Genkō 3), its patrons Sadaaki and Takatoki killed themselves, while Sadaaki’s son Sadayuki died in battle, so the archive came to be administered by the Shōmyōji temple, and the two collections were merged.

During and after the Muromachi period (1392-1573), the collection was often pilfered by warlords with scholarly ambitions such as Uesugi Norizane, Hōjō Ujimasa, Toyotomi Hidetsugu, Tokugawa Ieyasu, and Maeda Tsunanori. Although many works were lost in this manner, many others found their way into other important libraries of the early-modern period, such as the Ashikaga gakkō (Ashikaga Gakkō Iseki Toshokan), the Naikaku Bunko (Kokuritsu Komonjokan Naikaku Bunko), the Hōsa Bunko (Nagoya-shi Hosa Bunko), the Sonkeikaku Bunko (Maeda Ikutokukai Sonkeikaku Bunko), and the Toshoryō Bunko of the Imperial Household Agency (Kunaichō Shoryōbu Toshoryō Bunko), among others.

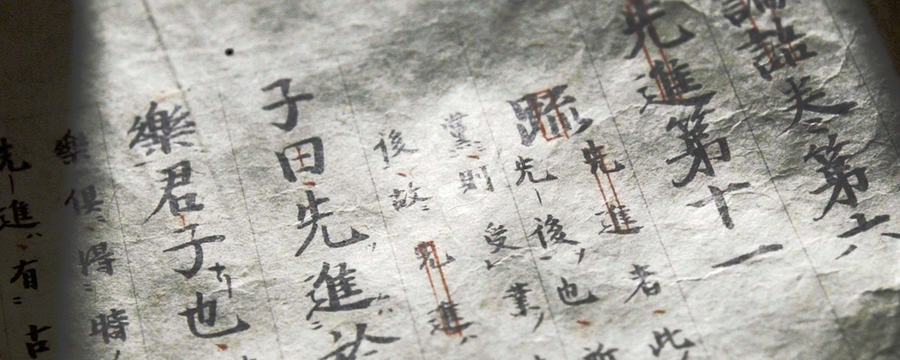

Save for the small number of texts that remain at the Shōmyōji, most of the collection is now scattered across various archives and it is only from the “Kanazawa Library” seal imprinted on these texts that we can determine their provenance. This goes to show what an important role sigillography (the formal study of seals) plays in bibliography and textual studies.

After the Kanazawa library ceased its activities, the roles of central archive and center of scholarly activity passed to the Zen monks in the Kamakura period whose close familiarity with Chinese publishing culture was to radically restructure the Japanese field of knowledge. Yet, it was the work of the Kanazawa-line Hōjō that, while not completely breaking with older scholarly practices, paved the way for these future developments, so they certainly deserve an important place in the history of Japanese books and scholarship.

Kanazawa Library Today

The portion of the collection that remained at the Shōmyōji temple is now at the Kanagawa Prefectural Kanazawa Library:

http://www.planet.pref.kanagawa.jp/city/kanazawa.htm (Japanese only)

Books formerly in the Kanazawa library and now at the Toshoryō of the Department of Mausolea of the Imperial Household Agency can be searched and viewed online on the Keio Institute of Oriental Classics’ online database: http://db.sido.keio.ac.jp/sido-tenseki/ (Japanese only)

Share this

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free