Secret transmission within scholarly families

No extant source tells us how the Analects were read for several hundred years after Emperor Ōjin’s time.

The earliest document of their influence dates from the reign of Empress Suiko (reigned 592 – 628), when Shōtoku Taishi (Prince Shōtoku, 574 – 622) quotes the Analects in his famous “Seventeen-Article Constitution”: “Harmony is to be valued above everything else.” It was also around this time that the imperial university (daigakuryō) was established with the purpose of training capable state officials. Here students studied the “Five Classics” (Book of Documents, Book of Odes, Book of Changes, Spring and Autumn Annals, and Record of Rites), the Classic of Filial Piety (Ch. Xiaojing) and the Analects, and also received specialized training in such subjects as literature and good writing through such texts as the Wenxuan (J. Monzen, Selection of Refined Writing), and the Erya (J. Jiga), the oldest surviving Chinese dictionary. The positions of Professor of Letter (monjo hakase) and Professor of Chinese Pronunciation (on hakase) were created to teach these subjects.

Two families of courtier-scholars

In the Heian period, in addition to the state university, all the main aristocratic clans (the Fujiwara, the Tachibana, the Ōe) established their own private academies. In addition to the classic texts of Confucianism, students here also studied a wide range of texts including the Records of the Historian and the Collected Writings of Bai Juyi (Baishi wenji, J. Hakushi monjū). Numerous collections of poems in Chinese (by Japanese poets) were compiled at this time, such as the Bunka Shūreishū (Collection of Literary Masterpieces, 818), the Kanke bunsō (Collected Writings of Sugawara no Michizane, early 10th c.), and the mixed Sino-Japanese collection, Wakan rōeishū (Japanese and Chinese Poems to Sing, early 11th c.).

Two aristocratic families in particular, the Kiyohara and the Nakahara, specialized in the academic study and reading of the Confucian classics (a field known as myōkyō, or, “Classics”). Each of them developed their own distinctive style of reading and glossing texts in Chinese, which were kept secret within the family and were only passed down to selected individuals, as was the norm in esoteric Buddhism. Does any material evidence of these reading traditions survive?

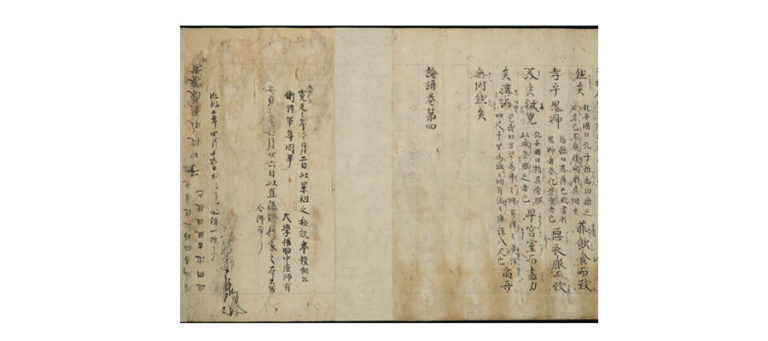

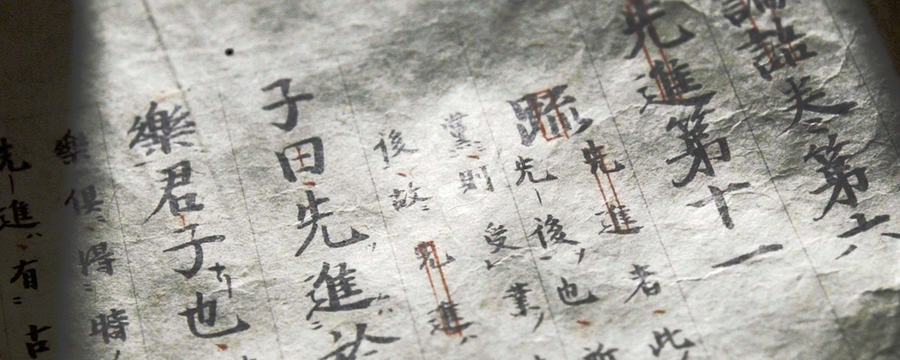

Only fragments of texts produced by the Nakahara family survive. They can be found at locations such as the Daigoji temple in Kyoto, the Tōyō bunko in Tokyo, the Kyou Archive of the Takeda Science Foundation in Osaka (formerly in the collection of Naitō Kōnan), and Ōtani University, also in Kyoto (formerly Kanda Kiichirō’s collection). Among these, the 1286 (Kōan 10) copy formerly in the holdings of the Kōsanji Temple in Toganoo, Kyoto, is the oldest surviving text of the Analects in Japan. The phrase “as secretly taught by our ancestors” in the colophon(in the hand of Nakahara Moroari, fig. 1) shows that this was a secret, not-for-public-circulation text.

Fig.1 Kamakura-period manuscript of the Analects 『鎌倉写論語』

Fig.1 Kamakura-period manuscript of the Analects 『鎌倉写論語』

Click to take a closer look

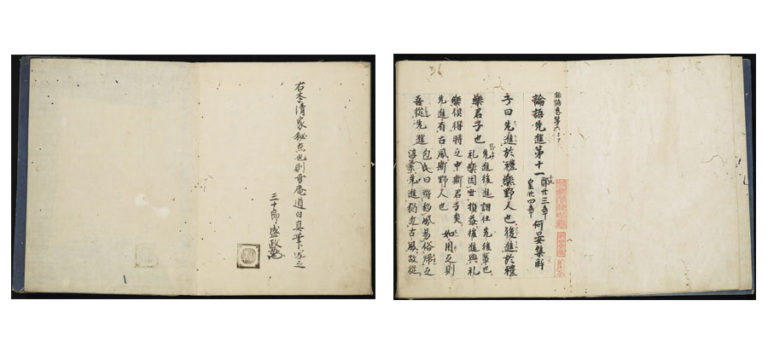

The scholarly tradition of the Nakahara family seems to have ceased around this time. By contrast, the Kiyohara style of reading and translating the Analects dominated in the Muromachi period (14th to 16th c.) (figs. 2 and 3).

Fig.2 Kiyohara-version Analects (a) 『清原家論語』

Fig.2 Kiyohara-version Analects (a) 『清原家論語』

Click to take a closer look

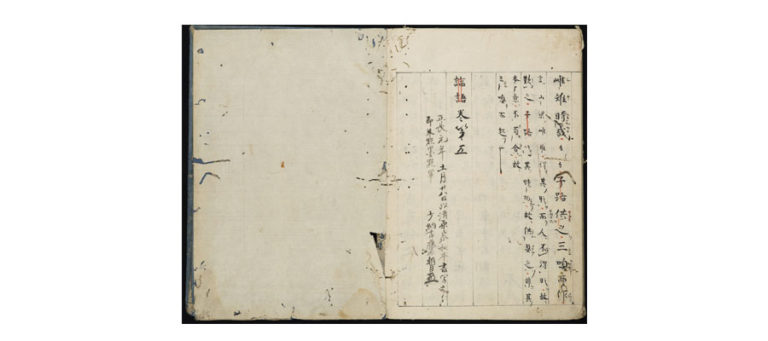

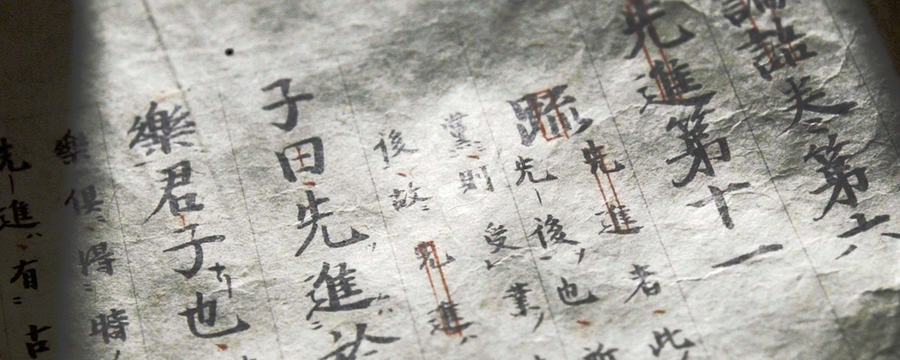

Fig.3 Kiyohara-version Analects (b) 『清原家論語』

Fig.3 Kiyohara-version Analects (b) 『清原家論語』

Click to take a closer look

Some trace the origins of the Kiyohara family as far back as Prince Toneri, a son of Emperor Tenmu (r. 673-686), and from the time that Kiyohara Hirozumi was first appointed Professor (Hakase) in the Heian period, they prospered as a scholarly lineage, with Kiyohara Yorinari taking on the role of personal tutor to Emperor Takakura in the late-Heian period. In the Kamakura period (1185-1333), Yorinari’s grandson Noritaka moved to Kamakura and made a significant contribution to the cultural development of the Kantō area. His scholarly activities included teaching how to read the Analects (copies of the text of his lectures are at the Tōyō Bunko and at the Department of Archives and Mausolea of the Imperial Household Agency (Kunaichō Shoryōbu).

Between the late-Kamakura and early Nanboku-chō periods (13th-14th c.), Yorimoto (the son of Yorinari’s fifth generation descendant, Yoshieda), lectured extensively on the Analects and carried the family tradition into the Muromachi period. (The text he used for his lectures is now at the Dai-Tōkyū Kinen Bunko )

The Kiyohara family in the Muromachi period

The most representative Kiyohara scholar of the Muromachi period is without a doubt Kiyohara Nobutaka (1475-1550), who joined the family from the Yoshida lineage of Shinto priests-scholars. Thanks to his wide-ranging education, he lectured widely on subjects ranging from the history and myths of Japan (kokugaku) to Confucianism, and his dominance of the scholarly world was unrivalled. A fair number of texts by him survive. The book known as the “Shōhei-era Analects”, for instance, is based on a text by Nobutaka. Once again, however, it being marked as “secret teaching” shows that it was meant to be copied and read only by a few specially-chosen readers. According to the colophon, the 1428 (Seichō 1) text is also a copy of a Kiyohara-family text, and so it is almost certainly another example of “secret transmission” (hiden) within the family.

The family’s tradition of scholarship was continued by Nobutaka’s son Yoshida Kanemigi and his grandsons, Edakata and Bonshun, in the late-Muromachi period, and by Hidekata in the Keichō era (1596-1615). In the Edo period, Hidekata’s son Katatada founded a successful new branch, the Fushihara family (Fushihara-ke), which eventually seems to have absorbed the Kiyohara tradition of scholarship and reading. Even so, the traditional scholarly lineages of the medieval period seem to have declined rapidly with the rise to prominence of Hayashi Razan (1583-1657, see Week 4) and his circle. The texts of the Kiyohara family are now housed in the Kiyohara Bunko (Kiyohara Archive) of Kyoto University’s library and have been granted “Important Cultural Property” status by the Japanese government.

Share this

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Sino-Japanese Interactions Through Rare Books

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free