The Current Trends in Language Policies for Multilingualism

Share this step

The consecutive waves of large-scale immigration, EU free movement and, lately, rapid globalisation have increased linguistic diversity across Western Europe. This linguistic diversity can also be observed in schools and classrooms. It occupies the minds of schools, teachers and society as a whole.

A lot of schools are struggling with their emerging multilingual identity. Specialists emphasise the importance of multilingualism and multilingual school policies: it is an added value for all who aim to work and function in Europe. Children are encouraged to learn French, English, German, Spanish and Italian and, if possible, to use these new languages at home, with friends and on holidays. On the other hand, we see that the multilingualism of immigrant minority children, adolescents and their parents is often considered to be an obstacle to school success. Parents are sometimes encouraged to abandon their own language in their conversations with their children and give priority to the majority language. In some cases, children are discouraged or forbidden to speak any language other than the majority language while at school.

These language policies and practices are not inspired per se by a negative attitude towards the native language of immigrant minority children. Schools are truly concerned about the learning opportunities available to these children. And, therefore, children have to be submersed in a ‘language bath’: they will absorb the school language by hearing and speaking it all day long. However, by opting for this approach we must ask ourselves what the impact is on children when they hear/experience that learning foreign languages is an important asset and, at the same time, their mother tongue is but a ‘handicap’ for their future. So what is the impact of a monolingual school policy? And is a bilingual education model the only valid alternative? Can one ignore or even suppress the multilingual reality in schools and classrooms? How do schools have to deal with the multilingual reality?

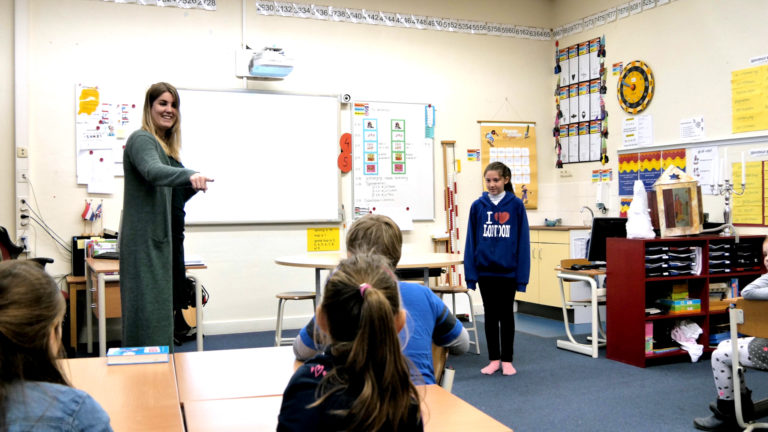

Multilingual Classroom

Multilingual Classroom

Monolingual versus multilingual education

Supporters of monolingual education policies are convinced that it is best to submerse non-native children in the majority language as soon and as often as possible. Within this perspective the home language of these children has no place in the classroom or elsewhere in school, and is not included in the curriculum. They are convinced that the use in school of the home languages of children from underprivileged immigrant backgrounds will obstruct the development of proficiency in the majority language.

On the other side of the argument, the ‘supporters’ of bilingual (or multilingual) education policies are convinced that children benefit from an education in their own language – in addition to or in combination with education in the majority language of schooling. They argue that education in the mother tongue provides a more effective basis for learning the language of schooling and on children’s well-being and self-confidence than total submersion.

Bi/multilingual education in contexts of migration in Western Europe: A brief history

From the 1970s onward, a variety of small-scale experiments in mother tongue instruction/bilingual education involving small proportions of immigrant children have been conducted across Europe. Over the years, bilingual education (i.e. the migrant languages used alongside the majority language as media of instruction in a variety of school subjects) in migrant languages reached a peak in Western Europe in the late 1970s/early 1980s. More specifically, the idea was taking root that teaching literacy and subject matter through the first language is desirable for immigrant children for pedagogical reasons rather than political and cultural reasons. In other words, it is the valorisation of the first language as a tool for learning which contributes to improving the school performance of immigrant children from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds. However, nowhere in Western Europe bilingual education in migrant languages has been able to establish itself as a fully valued teaching model within educational practice.

An important development of relatively recent date is the implementation of two-way immersion (TWI) models offering migrant languages in partnership with the dominant national language. In TWI learners have two different backgrounds (native speakers of the majority language and speakers of a minority language) and children are taught in relatively balanced groups.

Responding to language diversity at school: Going beyond binary thinking

Since the turn of the century, a return to cultural assimilation in Western Europe has marked a renewed emphasis on policies focusing only or mainly on learning the majority languages through hard-core submersion programmes. Under the pressures of a politically unfavourable climate and budgetary restrictions, education in migrant languages has increasingly come under attack.

However, backpacked with – among other valuable competencies – their multilingual repertoire, children enter the school. So, it is better to unpack and exploit it than to leave it in their rucksack and ignore or ban it.

School. By Ambermb CC0 Public Domain

School. By Ambermb CC0 Public Domain

This puts a language submersion policy and a multilingual education policy in a binary position. However, given the fact that both the language submersion models as the compartmentalised bilingual education models cannot present a cum laude school report; given the increased language diversity in schools and classrooms; given the fact that translanguaging or code-switching can be considered as the discursive norm in multilingual spaces and given the current highly polarised and rather unproductive debate about dealing with linguistic diversity in education, one can argue to go beyond the binary discussion for a new approach to multilingual learning at school. An approach which integrates exploiting children’s linguistic repertoires and learning the ‘language of schooling’, in which ‘translanguaging’ – as in other spaces – is used as the discursive norm at school and in the classroom. Or rephrased, ‘a multilingual social interaction model for learning’ as an alternative for a ‘language learning model’.

Among many other things, this implies a policy and interactive classroom practice that make children receptive to linguistic diversity and to create a positive attitude towards all languages and language varieties. This is called language awareness. It stands for making children (and teachers) sensitive to the existence of a multiplicity of languages, and the underlying cultures and frames of reference, in our world, and, closer, in the school environment. Functional multilingual learning is a step further in the positive dealing with children’s linguistic repertoires at school and in the classroom. It implies that a mainstream school adopts a policy and a teacher the practice of exploiting children’s full linguistic repertoire to enhance the opportunities for learning, as well as to reinforce their well-being, self-confidence, motivation and school and classroom involvement. The linguistic repertoire of children can be seen as didactic capital that explicitly can be drawn on to strengthen their (educational) development. Their linguistic repertoire can be a scaffold for learning the language of schooling and more general, for acquiring and unraveling new knowledge.

To conclude

There are no simple recipes or policies in addressing inequality, inequity and language in education. We have to move beyond the binary discussion of an exclusive language submersion model versus a traditional bilingual education model. In developing a language policy for multilingual schools, it is important to recognise that besides the school repertoire that children need to acquire, they also bring several additional repertoires to school. Repertoires that are not seen as a ‘problem’ or ‘a handicap’ for school success, but as ‘a richness,’ as an asset or an opportunity for learning and promoting equal opportunities.

Author: This piece was written by Prof Dr. Piet Van Avermaet, Centre for Diversity & Learning, Linguistics Department, Ghent University, Belgium.

Share this

Multilingual Practices: Tackling Challenges and Creating Opportunities

Multilingual Practices: Tackling Challenges and Creating Opportunities

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free