Sedentary behaviour and bone health

Share this step

Being physically active is vitally important in preventing major disease and in keeping bones healthy so as to avoid or minimise the risk of fractures. Contrastingly, sedentary behaviour (sitting, lying and screen-time, using very little energy) has negative effects on our overall health, as well as our bone health.

The negative effects on health are not just the loss of the benefits of being active. Being sedentary poses additional risks because it affects the body’s regulation. For example, inactivity is linked to a body composition that has higher fat than lean mass, higher levels of glucose and inflammation, factors which are linked to heightened risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and some cancers.

In adult bone, being inactive promotes the activity of cells that resorb bone (osteoclasts), which is a response to disuse.

Sedentary behaviour accounts for on average five and a half hours per waking day in adults and is rising nationally. Hours spent sedentary increase by approximately half an hour every five years over the age of 65 (British Heart Foundation, 2015).

Older adults lose bone mass through natural ageing every decade. Mature skeletons cannot lay down new bone as effectively as in youth but resorption with disuse will still occur. Without physical activity as a loading stimulus, sedentary adults compound risks of thinning of ageing bones. Furthermore, the loss of muscle mass with age exposes bones to higher impact forces and is accelerated by a sedentary lifestyle.

Sedentary behaviour will switch ‘on’ the cells that promote bones being re-sorbed, whilst switching ‘off’ the signals to maintain bone strength.

How to strengthen bone in older age

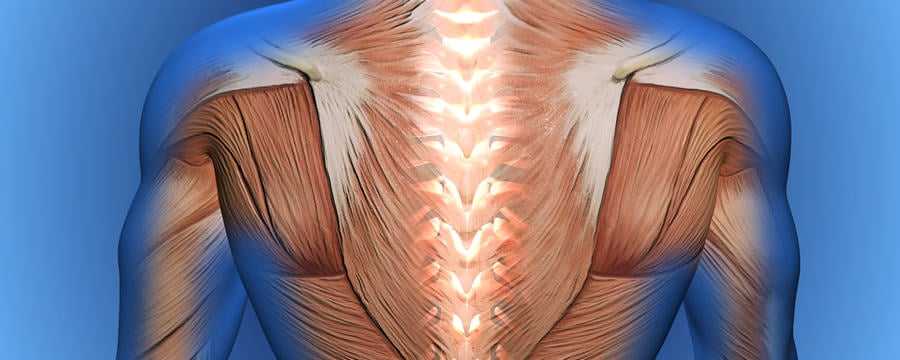

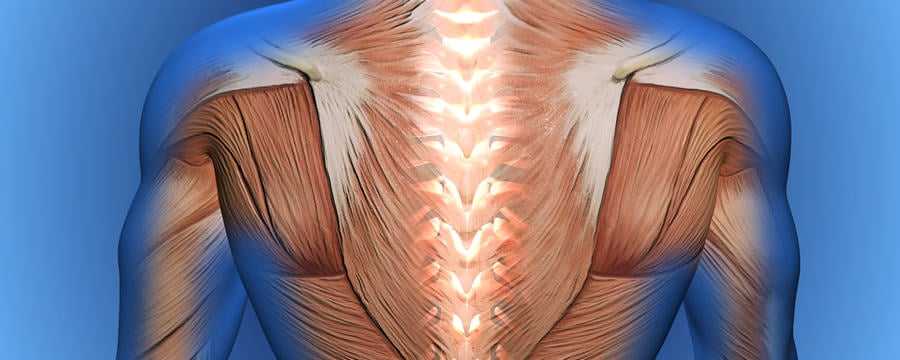

Bone adapts and strengthens when dynamic forces are applied to a specific area of the bone (mechanical loading). Loading needs to deform (strain) the bone to cause adaptation, either through ground reaction forces (for example a jump making contact with the ground impacting bone in the foot, leg and spine) or by contracting muscle attaching to bone (such as lifting weights to impact bones of the arm through traction on the muscle attachment or striking a ball with a racquet).

In the older adult, there is decreased ability to form new bone compared to the growing skeleton of an adult up to 30 years of age. The bone’s structure becomes stiffer and more brittle. However, it will still adapt positively to loading and therefore weight-bearing physical activity becomes a key factor in maintaining bone mass. The response of bone to loading/exercise may be to increase bone formation, but benefits can include prevention of normal age-related loss, or even reduction in the rate of loss. These are less desirable, but it is important to realise that there are risks of injury with very vigorous activity and a moderate exercise effect without injury is a good practical goal.

Activity is recommended that loads the bones in different directions and distributions to strengthen it to resist many different types of loading. Aerobics and racquet sports are therefore more effective in strengthening our bones than many repetitions of the same movement of the same vigour (as in distance running swimming or cycling – whether real or using a machine) and the upper body and torso bones can be stimulated by resistance exercise that requires muscle contraction.

How active and how often for bone health?

Current British and American medical guidelines advocate a minimum of five sessions of bone-loading exercise per week of at least 30 minutes duration, as well as two sessions of resistance exercise for adults over 65 years of age (Department of Health, 2011).

Greater benefits to bones will not be caused by the same number of longer durations of exercise. To improve the benefit, more than one burst of exercise per day (e.g. morning and afternoon) is more effective than a single long one. One easy way to tell if your exercise regimen is likely to affect your bones is to see if your muscles get bigger as you perform the exercises over a few weeks. If your muscles get bigger your bones are likely to be responding too. If your muscles develop stamina but not increased size, then the activity is unlikely to make your bones stronger.

The bones of adults with higher sedentary behaviour showed reduced strength at the hip according to a large study (Chastin, 2014). The association was strongest with sitting for long periods of time without break. People who broke up sitting time with even brief periods of weight-bearing activity had bone appearing stronger, even if overall they had spent the same time sitting. Therefore it may be important to interrupt your sitting time to stimulate bone most effectively.

Where a bone is weakened, such as in an older person with osteoporosis, it has reduced capacity to withstand load. Care may be needed to ensure that loading is appropriate to the ability of the individual to perform it without injury.

Finally, it is worth remembering that the effect of exercise goes beyond direct changes in bone mass. If you exercise, your balance, co-ordination and strength will be improved so you are less likely to fall, or if you do lose your balance, you may be more able to grab a support and not crash down hard enough to cause a fracture. As we know that exercise makes people feel good too, there are many excellent reasons to make sure it forms part of your daily routine.

Did you know that sedentary behaviour has such negative effects on our bone health? Could you incorporate more resistance exercise into you daily routine?

References

British Heart Foundation, Physical Activity Statistics 2015, British Heart Foundation centre on population approaches for non-communicable disease prevention, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, 2015

Chastin, S.F., Mandrichenko, O., Skelton, D.A.,The frequency of osteogenic activities and the pattern of intermittence between periods of physical activity and sedentary behaviour affects bone mineral content: the cross-sectional NHANES study, BMC Public Health, 2014 Jan 6;14:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-4.

Department of Health and Social Care, Physical activity guidelines: UK Chief Medical Officers’ report, 2019, Crown Copyright under the Open Government Licence v3.0

Share this

The Musculoskeletal System: The Science of Staying Active into Old Age

The Musculoskeletal System: The Science of Staying Active into Old Age

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free