Chemical Hazards and Health Effects When Welding

Share this post

Thousands of different chemicals are used in large quantities in various industrial processes, and new chemicals are introduced every year. At numerous workplaces worldwide worker exposure to chemicals represents a serious health hazard.

The type and extent of adverse health effects related to occupational exposure to chemicals depends on the intrinsic toxicity of the chemical, as well as whether the chemical is inhaled, deposited on the skin or ingested. It also depends on the intensity and duration of the exposure. The extent of exposure varies widely according to the industry, activity and country. Some chemicals cause adverse health effects in small quantities at low exposure levels while other agents in the work environment pose a low health risk even at relatively high concentrations.

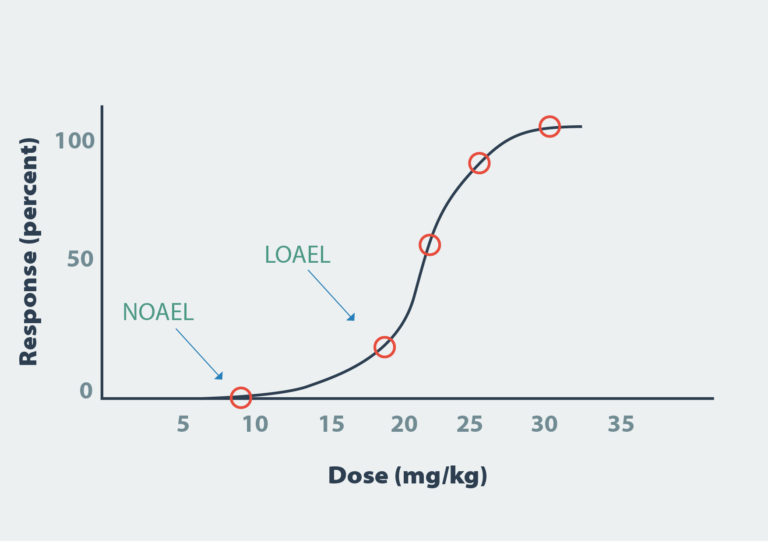

The basis for evaluating the instrisic toxicity of chemicals is in most cases animal studies. In a typical dose-response graph, the dose is plotted against the number or proportion of animals exhibiting a particular response. When used to characterize chronic toxicity for chemicals that do not cause cancer, the dose-effect relationship is examined to determine the highest dose at which no observable adverse effect is seen (NOAEL – No Observable Adverse Effect Level) or the lowest dose at which an adverse effect is observed (LOAEL – Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level). The value on the curve is then extrapolated to humans to estimate the maximum exposures that are likely to be without adverse effect. Thus, even a chemical which is labelled as toxic will not cause toxic effects when the exposure level is below its NOAEL.

Dose-response graph to illustrate the relationship between the dose of a chemical and a toxic response. The highest dose at which no observable adverse effect is seen (NOAEL) and the lowest dose at which an adverse effect is observed (LOAEL) are indicated. © University of Bergen/Arjun Ahluwalia

Dose-response graph to illustrate the relationship between the dose of a chemical and a toxic response. The highest dose at which no observable adverse effect is seen (NOAEL) and the lowest dose at which an adverse effect is observed (LOAEL) are indicated. © University of Bergen/Arjun Ahluwalia

Although several of the health risks related to chemicals are well recognized, adequate control measures to reduce exposure to acceptable levels have not been established in a huge number of workplaces, particularly in developing countries. The consequences of chemical intoxication also lead to great economic burdens on individuals, families and on society.

The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), a federal public health agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services runs a web-site Toxicological Profiles which is a comprehensive resource when searching for information on toxicology, hazardous chemicals, environmental health, and toxic releases.

The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) is also an extensive source of information on the chemicals manufactured and imported in Europe. It covers their hazardous properties, classification and labelling, as well as information on how to use them safely. It focuses on safe use of chemicals and has information on how to replace hazardous chemicals with safer alternatives.

Occurrence

Chemical exposure occurs in virtually all industrial processes, and is particularly prevalent when processing chemicals and metals. For instance, risk of chemical exposures is often high in processes where volatile chemicals are used and during processes taking place at high temperatures, such as welding. Metals and metallic compounds can themselves be very hazardous, and can cause allergies or cancer. Gases and vapours can, depending on their chemical composition, cause mucosal membrane irritation, allergy, dermatoses, cancers and reproductive disorders. Exposure to vapours occur when using organic solvents, for instance turpentine/white spirits, toluene and alcohols in processes and industries. Examples include welding, painting, in laboratory work, as well as work in shoe factories, in the petroleum industry and in other chemical industries.

Example: Chemical hazards when welding

Welding is a complex process involving high temperatures and/or pressures as well as chemicals to fuse pieces of metal together. The base metal is melted and a filler material is often added to form a pool of molten material that cools to form a joint that can be as strong as the base material. As a result of the high temperatures, a range of hazardous components can be released from the base metal, the filler and from any surface coating/paint left on the metal piece. When not adequately protected, not only the welder, but also workers in the surrounding area will inhale these components in the welding fumes. Inhalation of particles, gases and vapour from the welding process can lead to airway irritations. Over time, chronic lung diseases such as asthma, bronchitis and emphysema may result from this type of work. Particular care should be taken when welding on stainless steel where the welding fumes contain the carcinogens nickel and hexavalent chromium. Welding on pre-coated metals also causes serious concerns when the paints involved contain hazardous agents such as lead pigments or isocyanates.

It is of great importance to know which chemical compounds are being emitted during welding in order to take the correct precautions for avoiding or minimizing any adverse health effects. There are a number of different welding methods in use, including Metal inert gas (MIG), active gas (MAG), Manual metal arc (MMA) (stick) and Tungsten inert gas (TIG) welding. The relative importance of emissions and exposure to hazardous compounds varies with the method used as well as with many other factors, including the base metal, the filler material and the coating on the metal surface.

Welders with and without respiratory protection. © M. Bråtveit and Jessy Zgambo

Welders with and without respiratory protection. © M. Bråtveit and Jessy Zgambo

The table below gives an overview of some chemical hazards released during welding and the acute and chronic health effects related to such exposure.

| Chemical hazard | Health effect |

|---|---|

| Aluminium; Welding and grinding aluminium alloys | Irritation of airways, asthma |

| Lead; Welding and grinding materials coated with lead-containing paint | Effects on blood and nervous system. Lead colic and kidney damage. Fetus damage and abortion |

| Epoxy; Welding and grinding surfaces coated with epoxy | Airway allergy and allergic dermatitis. Welding on epoxy can produce toxic decomposition products. |

| Phosgene; Welding on material cleaned by chlorinated organic solvents, e.g. trichloroethene | Acute toxic and corrosive. Causes irritation at low levels (ca. 5 – 10 ppm). High concentrations (> ca. 90ppm) is corrosive on lung tissue and are ultimately fatal due to suffocation. |

| Isocyanates; Welding and grinding on and close to polyurethane foam | Asthma and bronchitis. Eczema |

| Iron/iron oxide; Welding and grinding iron and steel | Connective tissue proliferation in lung tissue, siderosis (iron lung) with increased cough. |

| Carbon-monoxide (CO); Can occur when CO2 is used as shielding gas, e.g. in confined spaces | Binds to hemoglobin. Can lead to oxygen deficit. Acute symptoms vary with the concentration and duration of exposure, from tiredness and reduced concentration, through headache, dizziness and heart arrhythmia to unconsciousness and death |

| Chromium; Welding and grinding on stainless steel | Irritation of the airways, allergic dermatitis, bronchitis, lung cancer (hexavalent chromium) |

| Manganese; Welding and grinding on most types of steel | Symptoms of Parkinsons disease (tremor). |

| Nickel; Welding and grinding on stainless steel | Irritation of airways, allergic contact dermatitis, chronic airway infections, cancer in lungs, nose and larynx |

| Nitrous gases (NO and NO2); Produced at high temperatures. NO is often converted to NO2 | Acute irritation of the airways and reduced lung function. NO2 can lead to lung edema after short, but high levels of exposure |

| Organic solvents; Evaporate after cleaning/degreasing of workpieces | Eczema, chronic encephalopathy, polynevropathy |

| Ozone; Formed particularly in TIG-welding, but also some at MIG and MAG. | Low levels: Pungent/burning feeling in the throat, chest pain, breathing problems. Lung edema at high levels |

| Zinc/zinc oxide; Welding and grinding on galvanized materials | Acute irritation in nose and throat. Metal fume fever with symptoms similar to flu, but usually lasts only 24h |

© University of Bergen/Author: M. Bråtveit

Share this post

Occupational Health in Developing Countries

Occupational Health in Developing Countries

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free