The Construction of Cinematic Characters

Share this step

In this article, we’ll take a quick look at how cinematic characters are constructed, and then see if we can come up with broad approaches to creating our own characters.

Characters Bring the Role to Life

As we’ve already discussed, film is a dramatic form, an external form. We’re performing the story – literally physicalising the story – in contrast to the novel, where we depend on the writer’s description to stimulate the imagination of the reader. Our script is a set of directions – composed of dialogue and description of places and physical action – that instructs the performers and filmmakers. So, by its very nature, a script is incomplete until the film is made. When we’re thinking about character, it means that we’re creating roles to be performed, not finished characters. As writers, we must leave space for the performer, so it helps to imply, suggest and insinuate, rather than define. For many of us, this will be a new way of thinking about character.

Drama Characters

In a drama, it’s all about behaviour: characters are what they do. Full stop. Each character will make different choices and act on them in a distinct way. The story will be driven by the consequences of these choices. If the novel is concerned with the flow of thoughts and feelings, then the screenplay will be concerned with the flow of dramatic action, of change within characters.

What Does the Character Want?

When we develop stories, we may begin with a character or we may begin with a situation or we may start with a theme. In all cases, it soon comes back to whose story is this? What does this character want? What will they do to get it? We’re back to, “Somebody wants something and has trouble getting it.”

For most films, the major “wants something” is clearly stated, as it drives the main storyline. Win the game. Escape the killer. Care for a parent with dementia. Lose fifty pounds before Christmas… But if the character is no more than this one goal, then the story can quickly become simplistic or trite.

Creating Complexity in Characters

In fact, each of us wants many things, and we’re not always aware of these desires. And sometimes these desires are in conflict with each other, or represent opposing values. It’s the mix of these desires that will create complexity in our characters.

It needn’t involve psychoanalysis; in fact, this can be very simple. For example, each of us balances a love of adventure and excitement with an instinct for caution and self-preservation. A trip to Grand Canyon may see one character cautiously inch toward the lip, while another character may race forward and slide the last two metres to end up with toes hanging over the chasm.

We All Play Different Characters

And we see a slightly more complex drama play out in pubs and bars every Saturday night. Our twentysomething character is a little tipsy, all alone, and he or she hasn’t been in a relationship for a long time – years, months, weeks, days, hours – whatever is a long time for this person. The character locks eyes with someone else down the bar… and the drama begins. Rationally, the character knows that pulling people in a bar is seldom the road to long-term happiness. But emotionally, the character hasn’t been in a satisfying relationship in – months, weeks, days. A long time… And at an instinctual, unconscious level, our character happens to be in prime reproductive condition, so the hormones are screaming, “Reproduce. Now!” Throw in a little alcohol, and things sometimes happen…

The same sort of drama plays out in a soldier waiting in a trench moments before the attack. Rationally, the character knows his duty; emotionally, he’s terrified; instinct tells him to run for this life.

Situations Define Characters

The action that comes out of these encounters – whether it’s the Grand Canyon, the bar or a foxhole –will define our character. And in each case, the decision will take the characters to new situations, where they will be presented with still more choices. The story will be built from the responses to this chain of questions.

Of course, it’s more than mere desire that defines a character. At the start of the race, each competitor wants to win. But each character will exhibit a mix of strengths and flaws; all will have different mental processes; and each will have a variety of physical characteristics. All of these considerations go into the mix that defines our characters.

Character Development Never Ends

The process is never static. This is how the character and story structure work together. The story begins because “Somebody Wants Something”, but it’s the “Has Trouble Getting It” that will define the character. It’s the writer’s job to construct a story that keeps testing our characters, asking new questions and forcing hard decisions.

Over the course of the story, the response to these challenges will trigger the internal changes commonly known as a “character arc.” In most cases, this will see the character change in a beneficial way. They may grow, heal, or perhaps find redemption for past misdeeds. This is most common story approach, and it can be very satisfying for an audience that is emotionally invested in a character.

A Change of Character

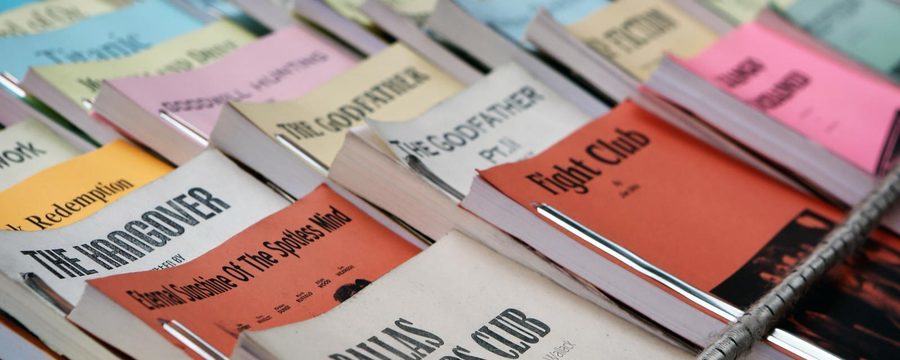

But we also see films that feature an anti-hero or a character who undergoes some sort of shadowy transformation. This is famously seen in The Godfather, where Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone begins the story as a war-hero with no interest in the family ‘business’, and then gradually develops into a murderous crime boss.

There are films that feature little or no character change, but it’s become rare. Sometimes it is done in satire, for comic effect, or in some genres, e.g., Horror, that aim to suspend or thrill. And sometimes it’s done to carry a specific theme or make a statement about a particular aspect of the human condition. There is no one right or wrong way to construct the character arc, as it will be determined by the needs of each story.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free