The Tragedy of Antony -Cleopatra’s scene with her children

Share this step

Here, we study a scene from Mary Sidney Herbert’s translation “The Tragedy of Antony” by reading it and making notes. She based her translation on the 1585 edition of the French dramatist, Robert Garnier’s “Marc Antonie”, which focuses on the figures of Antony and Cleopatra in their defeat by Octavius Caesar. Tragedy arises from their decline and suicides, the same pattern found in Shakespeare’s later dramatization of the story.

The scene below is from Act 5 in which Cleopatra responds to Antony’s suicide and determines to follow him. It features her children and their tutor as well as her female companions Charmain and Eras.

Critics such as Anne Lake Prescott and Danielle Clarke have pointed out that Mary Sidney Herbert’s publication of the play ‘done in English by the Countess of Pembroke’ in two editions of 1592 and 1595, take it beyond the household and into the worldly domain of politics and war (one which Mary Sidney Herbert knew well as Marion Wynne-Davies pointed out in the interview in the previous step). The questions below ask you to identify public and private elements of the scene as you read it.

We do not have any record of a contemporary performance of the play, but Mary Sidney Herbert does start her text with a list of ‘The Actors’. As you are reading, think about how the scene might work as a piece of theatre, staged in a household. Mary Sidney Herbert completed her translation with the words ‘At Ramsbury 26 of November 1590’ so it is possible that Ramsbury, one of the Pembroke houses, was the site of an imagined or real performance.

Now proceed to read the scene. You can work on the text below or read from the downloadable PDF document with more extensive footnotes.

- Make a note of any words of lines that relate to the public lives of Cleopatra and her family.

- In another colour, or in another list, make a note of words or lines that focus on their private lives.

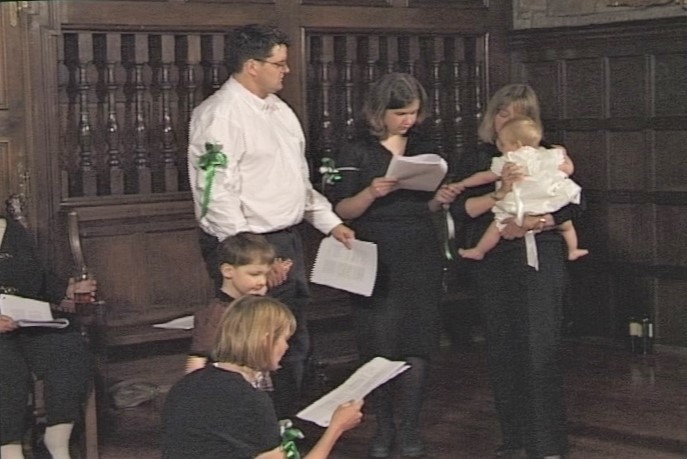

- What contrasts or overlaps are there between the two? Take these ideas forward to the next activity, where you can see an extract from the staged reading of this scene pictured in the image.

Extract from Act. 5

[The family tomb within Cleopatra’s palace]

[Enter] Cleopatra. Euphron. Children of Cleopatra. Charmion. Eras.

Cleopatra:

O cruel fortune! O accursed lot!

O plaguey love! O most detested brand!

O wretched joys! O beauties miserable!

O deadly state! O deadly royalty!

O hateful life! O queen most lamentable! [5]

O Antony, by my fault buriable!

O hellish work of heaven! Alas, the wrath

Of all the Gods at once on us is fallen.

Unhappy queen! O would I in this world

The wandering light of day had never seen! [10]

Alas, of mine the plague and poison, I

The crown have lost my ancestors me left,

This realm I have to strangers subject made,

And robbed my children of their heritage.

Yet this is nought (alas!) unto the price [15]

Of you dear husband, whom my snares entrapped;

Of you, whom I have plagued, whom I have made

With bloody hand a guest of mouldy tomb:

Of you, whom I destroyed; of you, dear lord,

Whom I of empire, honour, life have spoiled. [20]

O hurtful woman! And can I yet live,

Yet longer live in this ghost-haunted tomb?

Can I yet breath! Can yet in such annoy,

Yet can my soul within this body dwell?

O sisters, you that spin the threads of death! [25]

O Styx! O Plegethon! You brooks of hell!

O imps of night!

Live for your children’s sake;

Let not your death of kingdom them deprive.

Alas what shall they do? Who will have care? [30]

Who will preserve this royal race of yours?

Who pity take? Even now meseems I see

These little souls to servile bondage fallen,

And borne in triumph.

Ah most miserable!

Their tender arms with cursèd cord fast bound [35]

At their weak backs.

Ah gods what pity more!

Their seely necks to ground with weakness bend

Never on us, good gods, such mischief send.

And pointed at with fingers as they go.

Rather a thousand deaths

Lastly, his knife [40]

Some cruel caitiff in their blood imbrue.

Ah my heart breaks! By shady banks of hell,

By fields whereon the lonely ghosts do tread,

By my soul, and the soul of Antony,

I you beseech, Euphron, of them have care. [45]

Be their good father, let your wisdom let

That they fall not into this tyrant’s hands.

Rather, conduct them where their freezèd locks

Black Ethiopes to neighbour sun do show;

On wavy ocean, at the waters will; [50]

On barren cliffs of snowy Caucasus;

To tigers swift, to lions, and to bears;

And rather, rather unto every coast,

To every land and sea – for nought I fear

As rage of him, whose thirst no blood can quench. [55]

Adieu dear children, children dear adieu:

Good Isis you to place of safety guide,

Far from our foes, where you your lives may lead

In free estate devoid of servile dread.

Remember not, my children, you were born [60]

Of such a princely race; remember not

So many brave kings, which have Egypt ruled,

In right descent your ancestors have been;

That this great Antony your father was,

Hercules’ blood, and more then he in praise. [65]

For your high courage such remembrance will,

Seeing your fall, with burning rages fill.

Who knows if that your hands, false destiny,

The sceptres promised of imperious Rome

Instead of them shall crooked sheep hooks bear, [70]

Needles or forks, or guide the cart, or plough?

Further reading

Copies of the full text are published in

“The Collected Works of Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke” Volume I, edited by Margaret P. Hannay, Noel J. Kinnamon and Michael G. Brennan (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), pp. 139-207 and in

C. P. Cerasano and Marion Wynne-Davies, “Renaissance Drama by Women: Texts and Documents” (London, Routledge, 1996), pp. 13-42.

There are many excellent analyses of the play and a good place to start is Barry Weller’s essay ‘Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke: “Antonius” (1592) in “The Ashgate Research Companion to the Sidneys” Vol. 2 Literature, ed. Margaret P. Hannay, Mary Ellen Lamb and Michael G. Brennan (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), pp. 199-209.

The two articles mentioned above are

Danielle Clarke, “The Politics of Translation and Gender in the Countess of Pembroke’s ‘Antonie’, “Translation and Literature” 6:2 (1997), 149-66.

Anne Lake Prescott, “Mary Sidney’s French Sophocles: The Countess of Pembroke Reads Robert Garnier,” in “Representing France and the French in Early Modern English Drama,” ed. Jean-Christophe Mayer (Delaware: University of Delaware Press, 2008), pp. 68-89.

You can also read the downloadable extract from my book “Playing Spaces in Early Women’s Drama’’ which discusses the scene in a household performance.

Share this

Penshurst Place and the Sidney Family of Writers

Penshurst Place and the Sidney Family of Writers

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free