Burial practices and grave goods

Share this step

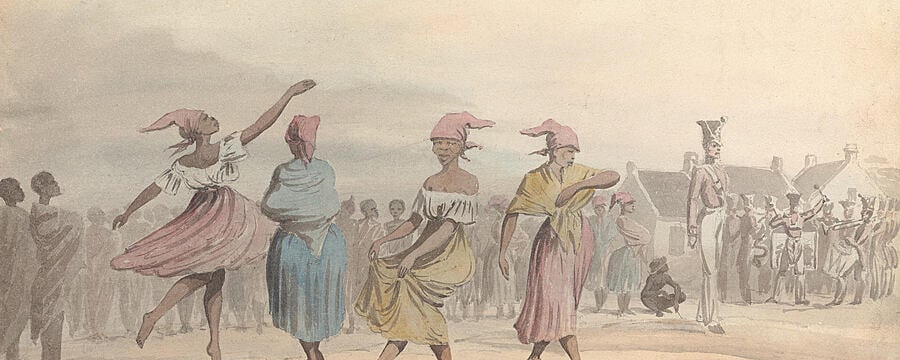

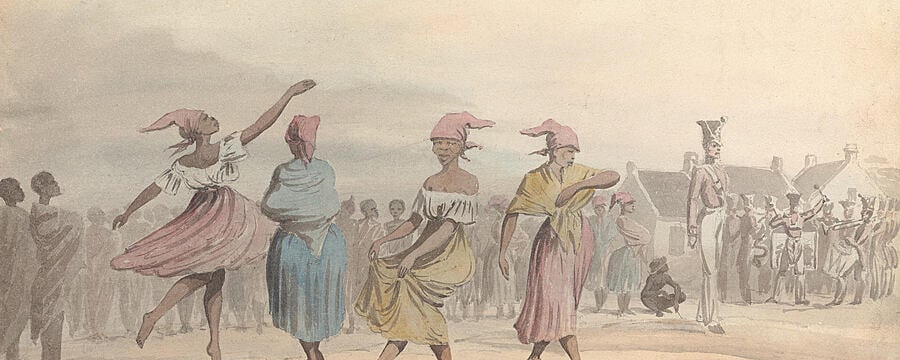

Thousands of enslaved labourers are buried in unmarked plantation cemeteries. Situations can arise where archaeologists uncover a burial ground that may be in danger of being destroyed and can excavate portions in order to safely re-inter the remains elsewhere. This process can also provide a wealth of information on slave lifeways beyond demographic patterns of gender and age at the time of death.

There are many case studies of skeletal remains in both British and French colonial contexts, that confirm that enslaved people endured harsh living conditions and often suffered from malnutrition. While many aspects of their lives were dictated by the slaveholder, including where they would be buried, fascinating aspects of enslaved peoples’ private lives can be revealed through slave cemeteries1. This is especially interesting in the context of community social dynamics. Archaeologists have found variation in burial patterns across colonies but also between neighbouring estates on the same island.

– Warning: the following image is of human remains. –

“Skeleton and Burial, Newton Plantation Slave Cemetery, Barbados” http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2267

“Skeleton and Burial, Newton Plantation Slave Cemetery, Barbados” http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2267

It seems that slave communities exercised a degree of independent control over their burial practices. Many of these practices demonstrate a continuation of African custom and beliefs, despite British colonial cultural norms. For example, at Seville plantation in Jamaica, there was at least one recovery of an individual buried in the house-yard of an enslaved —in keeping with common African mortuary practice observed through ethnohistorical research in contemporary Ghana. In fact, as it was during the slavery era, house-yard burials continue to be practiced in some contemporary African Jamaican communities.

One of the best studied slave burial grounds is the cemetery at Newton plantation in Barbados. Hundreds of enslaved individuals were interred here from the 1660s to the 1820s. Although portions of the site were excavated by Dr. Jerome S. Handler and Frederick W. Lange in the 1970s and 1990s, new insights are still being discovered in the 21st century.

Studies of material culture associated with some of the burials reveal physical links to African cultures despite the extremely difficulty for captives to transport important objects of spirituality, ethnic affiliation or even nostalgia. But it seems small objects like beads could have been smuggled on board by the owner or permitted to be retained by European purchasers.

At least one individual, aged 50 at the time of death, was buried with several personal items including copper wire bracelets on the forearms near the wrists and a pipe originating from the Gold Coast of Africa, similar to those found around the southern and coastal regions of seventeenth century Ghana. Even more remarkable was the discovery that the individual was buried with an African-influenced necklace comprised of canine teeth, cowrie shells, shark vertebrae, and glass beads of European origin. This necklace also had one unusual centrepiece: a red carnelian bead, originally from Gujarat, Western India, to many scholars’ surprise!

“Wire Bracelet, Newton Plantation Slave Cemetery, Barbados” http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2271

“Wire Bracelet, Newton Plantation Slave Cemetery, Barbados” http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2271

“Necklace components of Burial 72, Newton Plantation Slave Cemetery, Barbados” http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2269

“Necklace components of Burial 72, Newton Plantation Slave Cemetery, Barbados” http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2269

Interestingly, this type of bead necklace was common among some peoples of the Gold Coast region (modern day Ghana). Historic records can corroborate that between 1650 and 1750, a significant number of captive Africans from the Gold Coast were shipped to Barbados.

More importantly, necklaces like this were typically worn by priests and occasionally contained one long red carnelian bead. Thus, it’s believed that this individual was likely an African healer/diviner, a person who would have been viewed with great respect and admiration by his community.

Some studies have revealed insights to past social tensions within a slave community. Burials at Newton plantation (Barbados) and Seville plantation (Jamaica) suggest practices to control individuals who were disliked or viewed negatively by other members of the community by burying them at a solitary location, in a prone position (i.e., face down) or with a iron lock above the coffin to keep the deceased’s spirit confined underground. Comparative analysis of contemporary mortuary practices often helps to provide possible reasons for similar practices during the slavery era. In this case, anthropological evidence of West African mortuary data points to similar burial patterns being reserved for individuals deemed as witches or despised persons to be feared by their community. It is quite possible that these slave communities consciously made every effort to distance the undesired deceased in death as much as they might have socially ostracised them in life.

Generally, social and cultural respect for the deceased prevents archaeologists from excavating and disturbing slave burial grounds unless it is absolutely necessary. Those cases have provided a window into the private world of enslaved labourers, as they were not allowed to record their experiences in form of historical documents or books. We see glimpses into dynamic slave culture that, like any community, grappled with group social tensions. But we also gain insights into people who actively struggled to retained as much African cultural influence in life as well as in death against slavery’s oppressive system of control, violence, and dehumanisation. For more information on the Newton plantation slave cemetery, go to http://jeromehandler.org/.

1Historical archaeologists do not intentionally disturb or desecrate burial grounds solely for personal or scientific reasons. Most often, burial grounds are discovered by accident. If possible, surveys are performed, perhaps a small area is also excavated to assess the size and age of the site to help apply for governmental preservation status. Large scale excavations are only executed because the site is in danger of being destroyed by natural causes or the land is designated for development. Whenever possible, archaeological projects of this kind include the descendant community in decisions throughout the process. A common objective between the landowner, descendant community, and archaeologists is to agree that the human remains, grave goods, and other associated burial objects may be temporarily kept for analysis, documentation before being reinterred elsewhere. A final report is then made available to a wider audience.

Share this

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free