Second Maroon War 1795 – History of Slavery

Share this step

By this point, it should be clear that Jamaica during the eighteenth century was in constant internal turmoil between Whites and the enslaved community. Jamaica was Britain’s richest colony but despite the vast wealth generated by sugar plantations, enslaved labourers continued to be subjected to harsh working and living conditions. When not struggling with malnutrition due to apathetic planters, the average life span of the enslaved was reduced to a handful of years by torturous and violent punishment. Rage, resentment and fear were as normalised as the dehumanising treatment they received daily. However, as the third largest Caribbean island, the naturally green Jamaican scenery provided an advantage.

James Hakewill, ‘Haughton Court, Hanover, Jamaica’ Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Public Domain. This image from around 1820 shows an idealised view of the Jamaican landscape, but some details which hint at rebellion can be discerned. There are mobile cannon in front of the largest building. Buildings are positioned at the top of the hills to maintain lines of sight and aid defence. The mountains in the background provided excellent hiding places and refuge for escapees and rebels.

James Hakewill, ‘Haughton Court, Hanover, Jamaica’ Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Public Domain. This image from around 1820 shows an idealised view of the Jamaican landscape, but some details which hint at rebellion can be discerned. There are mobile cannon in front of the largest building. Buildings are positioned at the top of the hills to maintain lines of sight and aid defence. The mountains in the background provided excellent hiding places and refuge for escapees and rebels.

The sugar plantations occupied flat plains or gently rolling hills that butted up to steep mountains. The mountainous terrain with dense foliage made it possible for enslaved fugitives to not only disappear into the jungle-like landscape but to forge Maroon communities. Maroons not only successfully survived outside the plantation economies but also engaged in guerrilla raids against slaveholders and the colonial administration. Planation owners’ worries rose every time they heard the sound of the abeng (a bugle made from a cow’s horn to communicate across the mountains), wondering if their enslaved labourers would hear it as a call to abandon the plantation and take refuge with the fugitives.

Despite the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740 that ended the First Maroon war, Jamaica was continuously battling with real and imagined slave uprisings. The suppression of Tacky’s Revolt in 1761 did nothing to quell the constant worry of overt slave resistance. Ironically, the White inhabitants felt enslaved by the fear of losing their lives and the island to the Black populace; either by the enslaved labourers or by the Maroons sheltered in the mountains overlooking British colonial properties and towns, or the combination of both enslaved and Maroons in an island-wide resistance. The last decades of the eighteenth century only perpetuated their worries.

While the treaties ensured peaceful coexistence, it also led the Maroons to more contact with White society observing an odd racialised space in the colonial landscape where they were (mostly) free in their interactions with Whites while their racial brethren still laboured under the yoke of slavery. Furthermore, contact with colonial society led to an increase in grievances, citing an unease with growing White control over Trelawny Town Maroons. One issue was the struggle over who was allowed to possess human chattel. Maroons, viewing themselves as equal to Whites, also believed in their right to be slaveholders, even if it was not in the same institutional format of European colonists. Regardless, colonial administrators struggled to restrain Maroons from having enslaved Africans, even if it were a relatively few. In the eyes of British powers, only Whites should reserve the right to keep Africans as property.

The tipping point was the flogging of two Maroons in July 1795, convicted of stealing pigs, by an enslaved under the orders of British authorities. Historical evidence suggests that the Trelawny Town Maroons, heightened by a sense of superiority over Africans still living in bondage, were angered by both the conviction and punishment. They believed it should have been within their rights to try the accused and if necessary, punish them within their own community. British authorities, in meetings with the Maroons, were unsuccessful in quelling the situation, and thus, were officially at war. The Second Maroon War or more aptly, the Trelawney War of 1795, ended fifty years of stable coexistence between the planters and several Maroon communities. Ignoring Governor Lord Balcares’ order to surrender, the Maroons persisted in damaging British property and clashing with the militia.

However, this war would not last long. Mastiffs1, trained to catch the scent and hunt Black fugitives, were brought in from Cuba. Trusted enslaveds accompanied the militia to hunt down and destroy Maroon retreats and homesteads. British soldiers outnumbered the Maroons and surrounded the area. In the Spring 1796, after eight months of struggle, 550 Maroons and their families of Trelawney Town surrendered.

Deemed too dangerous and unpredictable, the Maroons were sent off the island in exile. After four months at sea, in late July 1796, three ships arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia with 549 Trelawney Town Maroons (majority of women and children). Hoping to reform the ex-insurgents, Halifax initially received them as labourers to help build the fortifications in Citadel Hill to guard from French attacks and assist in harvest season before the long winter.

Wentworth report on the Maroons, 21 April 1797, Commissioner of Public Records Nova Scotia Archives RG 1 vol. 52 no. 41 pp. 53-60 (microfilm no. 15238). Nova Scotia Archives. This document written by Sir John Wentworth, lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia. In it, he notes that the Maroons had survived a harsh winter but that he believed them to be reluctant to work, and would need the guidance of the British to instill discipline and ambition.

Wentworth report on the Maroons, 21 April 1797, Commissioner of Public Records Nova Scotia Archives RG 1 vol. 52 no. 41 pp. 53-60 (microfilm no. 15238). Nova Scotia Archives. This document written by Sir John Wentworth, lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia. In it, he notes that the Maroons had survived a harsh winter but that he believed them to be reluctant to work, and would need the guidance of the British to instill discipline and ambition.

The months at sea after surviving warfare situations in Jamaica left many sick and feeble and the cold climate only exacerbated their weakness. While Sir John Wentworth, the lieutenant governor of Nova Scotia, expressed paternalistic concern for the Maroons, the local administrators tried to force Christian conversion (even by bribery with bottles of rum) and sexually exploited Maroon women and girls. However, the true brunt of complaints centred on cultivation labour contracts and the lack of land ownership for the Maroons. The exiles petitioned the local administration several times with accusations of unlawful actions, misrepresentation, and direct lies by Wentworth. By 1800, after his loss of authority over the Maroon situation, Sir Wentworth despatched them to the recently established British colony in West Africa, Sierra Leone, where the British slave-trading fort on Bunce Island was still active.

Maroon Church in Freetown, Sierra Leone, est. 1808. Richard Anderson. This church established and built by the Jamaican Maroons in Freetown, Sierra Leone. The original roof timbers and pews were reportedly carved from the timbers of a condemned illegal slave ship.

Maroon Church in Freetown, Sierra Leone, est. 1808. Richard Anderson. This church established and built by the Jamaican Maroons in Freetown, Sierra Leone. The original roof timbers and pews were reportedly carved from the timbers of a condemned illegal slave ship.

The Maroons settled in a newly-established colony, which had been set up by the movement to abolish the slave trade. On the advice of Henry Smeathman, the botanist, Granville Sharp, Olaudah Equiano and others involved in campaigning against the slave trade had selected the area around the Sierra Leone River to re-settle the so-called ‘Black Poor’, indigent Londoners of African descent and their families. Enslaved people who had escaped their owners and fought with the British in the American Revolutionary War also joined the colony, as well as the Jamaican Maroons in 1800. Each group retained a distinct self-identification, but soon they would be out-numbered by survivors of the slave trade, who were sent to the colony after British abolition of the trade in 1807. We will look at this in-depth at the start of Week 4.

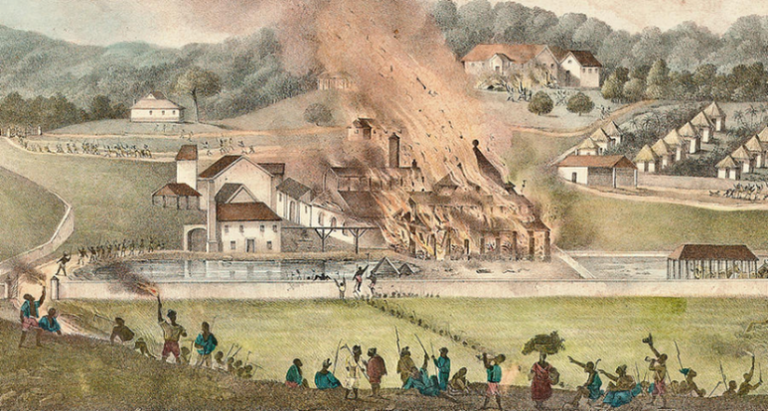

The beginning of the nineteenth century saw little change in the constant racial struggles. Despite the abolition of slave trade in 1807, conditions did not improve for Africans still enslaved on plantations in the Caribbean islands. Nor did Blacks surrender the desire for freedom and to destroy the brutal institution of violence and dehumanisation. Even on the eve of slavery’s true end, racial unrest would rock the prosperous island. On December 27, 1831, in another coordinated scheme involving between 60,000 and 300,000 enslaved Africans, Black Baptist preacher Samuel Sharpe, led a new rebellion. Initiated first with signal fires lit in the hills above Montego Bay, soon more than 100 plantation properties were set ablaze. Known as the Baptist War, the Christmas Uprising/Rebellion or the Sam Sharpe Rebellion, it would take the British military five weeks to suppress the uprising.

Destruction of the Roehampton Estate January 1832 Public Domain. Source: Wikipedia.org

Destruction of the Roehampton Estate January 1832 Public Domain. Source: Wikipedia.org

1Also called Cuban dogge, a sub-species of bullmastiff, particularly to Cuba. It is currently said to be extinct.

Share this

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free