The importance of social contexts

Share this step

Content for steps 1.7 and 1.8 have been provided by Julia Szymczak.

Julia’s main research question asks how do the social dynamics of healthcare work influence efforts to change medical practice?

The Healthcare Organisation as a Small Society

Healthcare organisations are groups of people who interact with other people, to provide care to people. This means that behaviour in these organisations is shaped by the social dynamics of groups of people. This includes:

- Conflict (and management of conflict)

- Status inequality and hierarchy

- Expression of emotion and interactions around emotion

- Identity work – the identity of the patient or professional, how identity shapes decision making

- Attribution of responsibility and accountability for risk

- Navigation of uncertainty – which the medical field is full of

Medical and healthcare workplaces have distinct cultures which shape decision-making and behaviour.

Why think of antibiotic use as a sociological phenomenon?

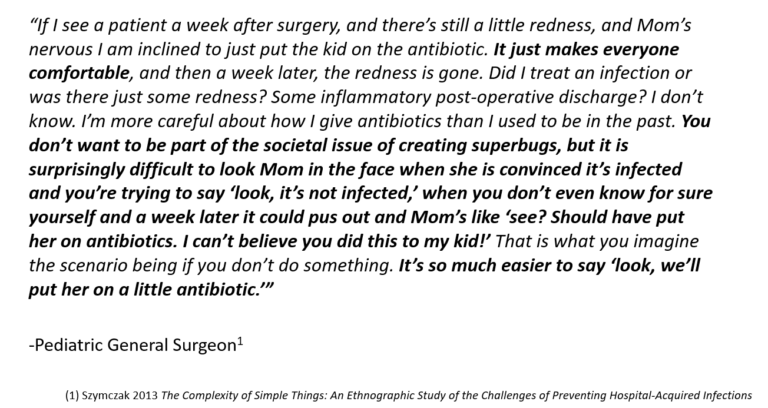

The above quote is from one of Julia’s research subjects, a Paediatric General Surgeon. It provides insight into how many social forces are at work when prescribing antibiotics – more goes into this type of decision than simply the need to treat bacteria.

The Social Determinants of Antibiotic Prescribing

What factors drive antibiotic prescribing decisions beyond clinician knowledge of appropriate practice or medical need?

Prescribing a drug is a highly social as well as clinical act:

- Means of communication – it is a way for a clinician to demonstrate concern

- Expresses power and facilitates social control, to define the situation at hand

- Produces income

-

A prescription is a tool to help clinicians navigate practical social challenges of care delivery

- How to react to patient demands

- How to project competence

- How to manage uncertainty about cause/cure of sickness

- How to end the clinical encounter

A prescription is a lot more symbolic than just treating a pathogen.

Antimicrobial Stewardship and Behaviour Change

Antimicrobial Stewardship interventions use a variety of different strategies (both persuasive and restrictive) to change the prescribing behaviours of front-line clinicians:

- Education

- Audit and feedback

- Restricted formularies

- Prior approval – putting rules in place

Prescribing behaviour is a complex, multi-factorial process.

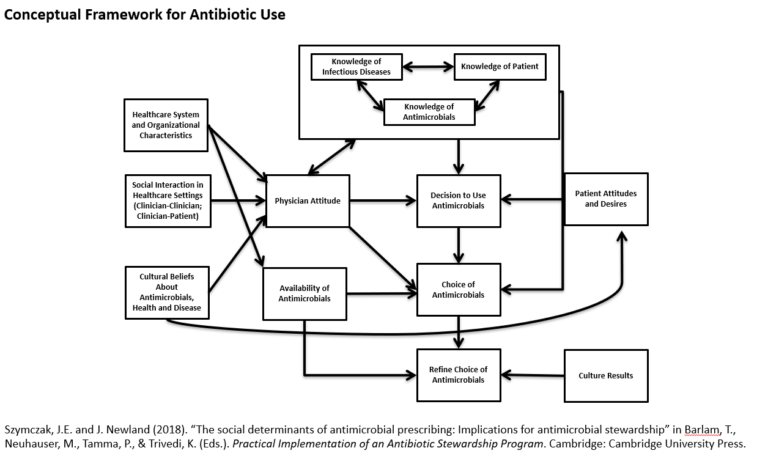

Conceptual Framework for Antibiotic use

Click here to take a closer look

The image above depicts a conceptual framework which visualises the idea that ‘the decision to use antimicrobials’ is embedded in a complex array of driving factors that need to be considered when trying to change their use.

The factors which will be focused on in this article are:

- Organisational characteristics that shape provision of care

- Social interaction happening between people in healthcare settings

- Culture of beliefs that patients and clinicians have about antibiotics, health, and disease

Relationships between clinicians

“Prescribing etiquette” refers to the idea of social norms and unspoken rules about what is appropriate in terms of how people interact with each other about their own and others’ prescribing practices. With regards to prescribing etiquette, there is a strong norm of non-interference: where clinicians are hesitant to correct colleagues, or be corrected, in relation to the use of antibiotics.

There is a role of hierarchy – junior physicians defer to those higher up, even if they know the decision being made is sub-optimal.

The opinion of senior colleagues and social networks is more influential than guidelines – there is variation in attitudes and practices according to medical speciality.

Risk, Fear, Anxiety, and Emotion

There is a perception that the risk of under-treating is far more of a motivating factor in decision-making than the individual patient risk (or population risk) from receiving unnecessary antibiotics.

- Adverse effects have limited impact on decision making

- Broad spectrum antibiotics feel safe, and carry an overarching goal of “preventing disaster in the next 24 hours”

- There is an emotional desire, shaped by the relationship with the patient, to provide all immediate therapeutic options regardless of wider population consequences

(Mis)Perception of the problem

Survey research finds that clinicians perceive antibiotic overuse as a problem generally, but not locally. There is a feeling of exceptionalism – guidelines do not apply to their patients, their past experiences and expertise trump guidelines, guidelines are ‘academic’ and therefore not always practical, and a general disbelief that they over-prescribe (even when faced with evidence that they do).

Contextual and Environmental Factors

There are time pressures which should be considered – the pressure to discharge patients quickly discourages a ‘watch and wait’ approach.

There are competing priorities – for example some facilities have patient satisfaction surveys: if the patient is demanding an antibiotic unnecessarily, the decision may affect their response in the survey. There is a need to balance the two organisational priorities.

The time of day also has an impact – decision fatigue can set in whereby at the beginning of the day the clinician may know the best decision, but as the day goes on and they become tired, hungry, etc, they may start to make more inappropriate decisions.

Why should we care about the social determinants of antibiotic prescribing?

Implications for Stewardship

Although antimicrobial stewardship interventions have been successful to a degree, they can still be improved.

Direct educational approaches generally do not result in sustained improvement: they may improve things a little but not to the desired degree, and over time the effects are attenuated.

Restrictive policies (techniques that stop clinicians from getting the antibiotics they want/making it harder for them e.g. getting approval) can be circumvented, for example:

- “Stealth dosing”

- Misrepresenting clinical information

- Combining non-restricted antibiotics to get desired coverage beyond AS recommendation

We also know that audits can be “gamed”.

Findings such as this indicate that we haven’t fully accounted for the social determinants of antibiotic use in the design of our interventions so far.

One of the ways which we can better incorporate these types of factors is to understand them more deeply. The next step will take an in-depth look at how we can use qualitative methodology to improve intervention strategies.

In the comments below please let us know:

- Have you ever felt pressured to prescribe antibiotics?

- How could this issue be mitigated?

Share this

Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance: A Social Science Approach

Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance: A Social Science Approach

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free