Food Labels: How Sustainable Is My Food?

If you sometimes wonder just how sustainable your food is, you are not alone. Consumers are increasingly choosing products that are sustainable [1]. But there is no one label that communicates ‘sustainability’.

Sustainability is a complex and multifaceted concept that aims to ‘meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ and encompasses both environmental and ethical aspects [2&3]. Sustainable diets are those

‘with low environmental impacts which contribute to food and nutrition security and to healthy life for present and future generations. They are protective and respectful of biodiversity and ecosystems, culturally acceptable, accessible, economically fair and affordable, nutritionally adequate, safe and healthy while optimising natural and human resources’ [4].

Organic

‘a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic agriculture combines tradition, innovation and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and a good quality of life for all involved’ [10].

Standards for organic farming in the EU are set by Regulation (EU) 2018/848 [11] (which updates current similar controls and comes into force in January 2021) and they relate to use of resources, protection of biodiversity and regional ecological balance, soil fertility, water quality and animal welfare. Food labels can use terms like ‘organic’, ‘bio’, and ‘eco’ to communicate that the product meets these organic standards and the EU organic logo should also appear on the product label. The code number of the control body and the place where the raw ingredients were farmed must accompany the logo.

Fairtrade

One of the most recognised fairtrade labels globally is the mark of the International Fairtrade system. This mark identifies products that fulfill social, environmental and economic standards that are agreed upon internationally and involve trading at better prices, traceability, and decent working conditions and fairer deals for the farmers and workers in developing countries [13]. Bananas, cocoa and coffee are the most sold fairtrade labelled products in 2018 according to Fairtrade International [14] which owns and licenses several certification marks that differentiate between products composed of a single fairtrade ingredient (such as bananas and coffee), products that contain at least 20% fairtrade ingredients (such as chocolate), and products that contain a single fairtrade ingredient.

Carbon footprints

The carbon footprint of a product refers to the total amount of greenhouse gases (GHGs, including CO2 (carbon dioxide), CH4 (methane) and N2O (nitrous oxide)) emitted across the life cycle of the product, converted to CO2 equivalents [9, 15]. There are various standards for the measurement and communication of carbon footprint [15] and the UK-based Carbon trust has 4 different types of label:

- CO2 measured: means the product’s carbon footprint has been measured and certified.

- Reducing CO2: means there’s a commitment to ongoing reductions in GHGs.

- Lower Carbon: means this product has a lower certified carbon footprint than the market leading product in the category.

- Carbon Neutral: means the footprint has been reduced and any remaining GHG emissions have been offset [16, 17].

The complexity of the system does mean that consumers have difficulties comparing products based on their carbon labels. However, the use of colour coding to show relative emissions can improve the effectiveness of the label [16].

Local or short-supply chain labels

Consuming local food reduces food miles, helps to preserve the environment and support the local economy, among other benefits.

Labels showing that the product is local or that it has a short supply chain [6]. These are sometimes used even though there is no agreed definition of what ‘local’ means across the EU yet [18].

Animal welfare labels

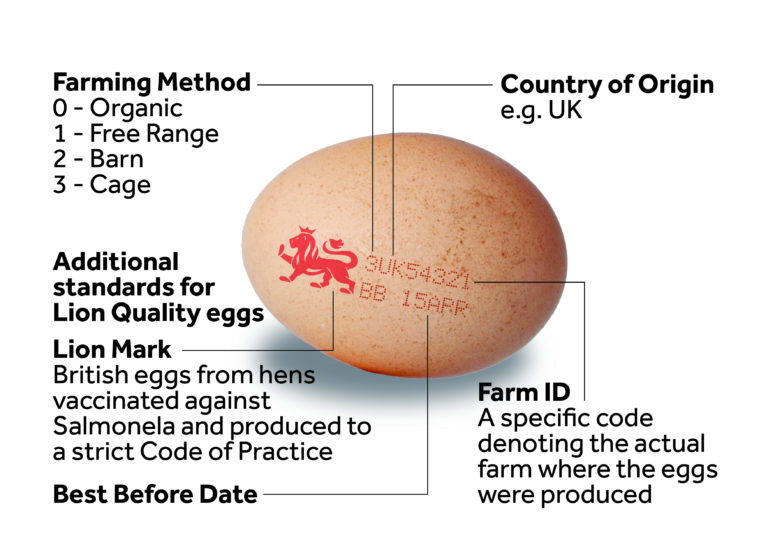

There is currently only one compulsory animal welfare labelling system in the EU, the one for eggs [19]. This compulsory system differentiates between ‘organic’, ‘free range eggs’, ‘barn eggs’ and ‘eggs from caged hens’. ‘Free range eggs’ come from hens that have continuous daytime access to open-air runs that are mainly covered by vegetation [20]. For ‘barn eggs’ there is no explicit requirement that hens should have access to open air, however, the barn conditions are better than those of caged hens.

The Certified Animal Welfare Approved by AGW label guarantees high welfare management, outdoor access and sustainable production. Products that meet the standards of this independent, nonprofit farm certification programme by A Greener World (AGW) can carry the label [21]. Some countries have their own scheme such as Ètiquette Bien-Être Animal from France and ‘Beter Leven’ from the Netherlands.

There are specific labels for seafood. The Marine Stewardship Council label refers to sustainable sourcing of wild fish and seafood, whereas the Aquaculture Stewardship Council logo refers to responsible sourcing of farmed fish or seafood.

We’re sorry we couldn’t reproduce the labels we’ve discussed in this article because the organisations concerned are rightly careful about who displays them and why. You may also find differences in the labels used in different EU countries [15]. Thankfully, technological solutions are emerging to help you find out what sustainability labels mean. The Giki app allows you, among other things, to scan a product in a UK supermarket and find out its carbon footprint, animal welfare credentials and production system (organic or conventional).

Some labelling on pre-packaged food products can refer to the packaging, emphasising some characteristic that makes the package more sustainable. For example, that the packaging is made of bioplastics (material that is biobased or biodegradable) or that it is recyclable. Thus, some communication on packages can be about the packing itself rather than the food inside, contributing to how sustainable a food product is overall.

Choosing sustainability-labelled products is only one aspect of adopting a sustainable diet. Different types of food differ widely in their environmental impact. Changes in diet, such as eating less meat, can have greater benefits for the environment [21, 22].

If you’d like to make changes to your diet for sustainability reasons, there are some simple tips provided by the UK-based charity Sustain.

Even better, the EAT-Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, Health proposes The Planetary Health Diet which is good both for you and for the planet. It encourages a move towards consuming more vegetables, fruits, legumes and nuts and also provides tempting recipes and inspiring tips.

But even this isn’t enough on its own! The EAT-Lancet report also stresses the need for improved global food production systems and the reduction of food waste.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free