A brief history of gender (in)equality

The nature and causes of gender inequality is multifaceted and complex and beyond reduction to a few core factors, but in this section we’ll review some of the key moments in history that contribute to this story, addressing various manifestations of inequality, and briefly consider their effects.

Suffrage

One of the central and, thanks to the suffrage and suffragette movement, probably one of the most well-known aspects of gender inequality, is the right to vote and how women were restricted or prohibited from voting. The right to vote is a fundamental right as it involves the capacity to contribute to the election of the government that will represent your views. Given the power vested in government to make decisions that affect the daily lives of citizens it is important that those affected (of voting age) can have a say in who makes those decisions.

Voting rights were afforded to women much later than men, and often this was achieved through hard won battles. The suffrage movement (particularly associated with the leadership of Milicent Fawcett) sought to achieve equality for women through peaceful and legal means such as petitions, whereas the suffragettes were more militant in their action. In the UK this movement is best known through the work of Emmeline Pankhurst who founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. This group attempted to enter parliament, heckled members of parliament, damaged and chained themselves to property and consequently faced abuse from the media and were physically assaulted by the police.

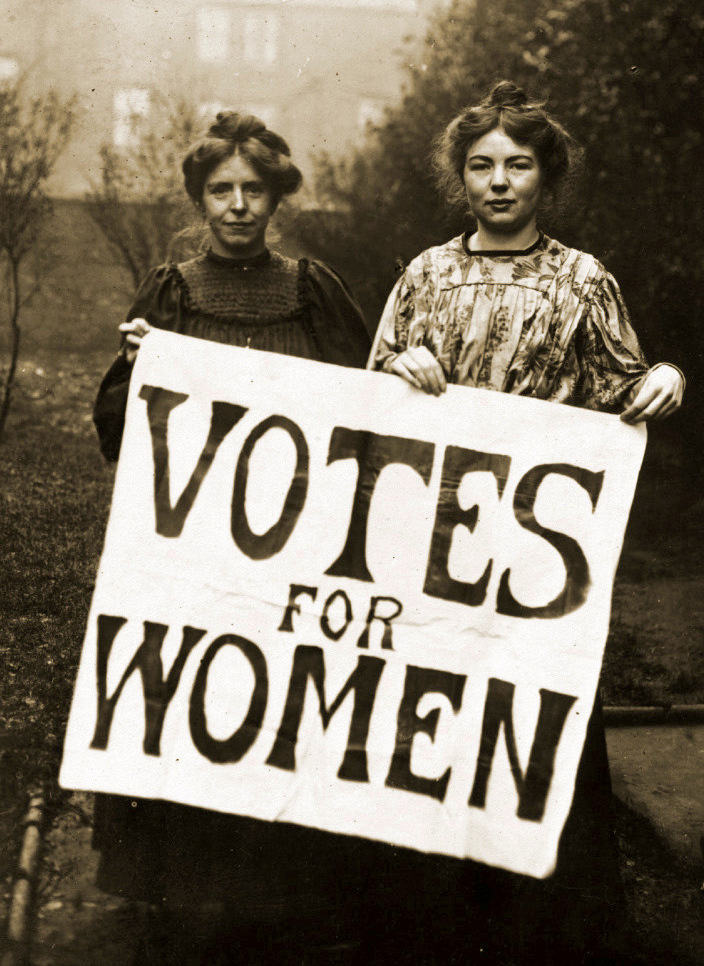

WSPU leaders Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst, circa 1908

WSPU leaders Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst, circa 1908

The aims of the suffragists were not twentieth century ideas. For example, in 1869 John Stuart Mill published an essay on the equality of the sexes in “The Subjection of Women”, and men as well as women were signatories on appeals for equal voting rights, but these arguments were not persuasive to those in power. A useful timeline for the suffrage movement in the UK can be found on the British Library website, and others exist for different countries. The dates below set out some of the milestones (although it is not exhaustive):

| Date | Location | Event |

| 1932 | UK | A petition is made to an MP calling for unmarried women who to be given the right to vote. |

| 1848 | US | Women’s first suffrage conference calling for equal voting rights for women as afforded men. |

| 1893 | New Zealand | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1897 | UK | The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies is formed. |

| 1903 | UK | The Women’s Social and Political Union was founded (linked to the Suffragette movement). |

| 1906 | Finland | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1915 | Denmark | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1918 | UK | Some women over 30 given the right to vote. |

| 1918 | Austria, Germany, Poland and Russia | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1920 | US | Congress adopt 19th Amendment to extend voting rights to all citizens of voting age (giving equal voting rights to women, although race could still prove to be a barrier). |

| 1921 | Sweden | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1928 | UK | Women over 21 given the right to vote (giving them equal voting rights). |

| 1931 | Spain | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1944 | France | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1950 | India | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1957 | Malaysia, Zimbabwe | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1962 | Iran, Morocco | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1971 | Switzerland | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1989 | Namibia | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 1993 | Kazakhstan, Moldova | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 2005 | Kuwait | Equal voting rights given to women. |

| 2011 | Saudi Arabia | Equal voting rights given to women. |

What is immediately notable is the extended timeline for equal voting powers to be given. This is a reminder that whilst many of us may feel that formal equality has been in place for a considerable period of time, for many countries this has not been the case. Furthermore, the persistent nature of this inequality worldwide indicates that the assumptions underpinning gender inequality are often resistant to change.

Marriage

Women’s livelihoods were historically significantly dependent on who they married as their roles were typically seen as being to raise children and manage the home whereas the husband earned the income and acted as the head of the household and prime decision-maker. Upon becoming married wives fell under the protection of the husband and often became one person in the eyes of the law affording them no rights to own property or to retain their earnings – all of which became the property of their husband.

Women also faced restricted inheritance rights, typically limited to personal effects, rather than land or property, and where primogeniture was in place – where the eldest son inherited the property – the female heirs could only benefit in the absence of a male sibling (the removal of male primogeniture for succession to the British throne, where the eldest male child is preferred to the female, in favour of absolute primogeniture (the first born regardless of sex) was enacted as recently as 2013). Even where the wife had wealth in her own right prior to marriage, this became the property of the husband upon marriage.

In England and Wales the restrictions on property ownership was the case until the 1870 Married Woman’s Property Act. Children resulting from the marriage were also the property of the husband, and this only began to change in England and Wales in the late 1830s, but it remained limited and in favour of the father. There were also gender differences in the criteria for divorce, making it much easier for men to divorce women. Wives were not entitled to property from the marriage, leaving them destitute should they be successful in divorcing their husbands. Even though this was improved in the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1957, a bias making it easier for the man to pursue divorce remained.

Similar patterns can be found in other countries. The various states in the US brought in Married Women’s Property Acts through the 1840s and 1850s. It was addressed in the 1870 and 1880s in Sweden, but although property rights were extended for women, the guardianship of the husband over the wife remained.

A wife’s body was also the possession of the husband, to the extent that – in the eyes of the law – a husband could not rape his wife as her consent, upon marriage, could be assumed. Germany outlawed spousal rape in 1997. Prior to that rape was perceived as ‘extramarital intercourse’ and could only affect a woman. The change in law in 1997 made this gender neutral and removed the marital exemption so marital partners could also be prosecuted. Marital rape was outlawed across the US by 1993, in England and Wales in 1991, and Zambia in 2010.

But many countries still do not recognise spousal rape, including Algeria, Barbados, China, Egypt, Gambia, India, Jamaica, Kuwait, Libya, Maldives, Nigeria, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. In England and Wales there was a considerable period of time from those who first spoke against marital rape, such as John Stuart Mill in the 19th century, through to extensive political debate from the 1970s before the law was finally changed in 1993. The debates reflect the predominant views that non-consensual intercourse between man and wife should be viewed differently to that forced on a woman by a man to whom they are not married.

The marital contract, property law and voting restrictions represents what is understood by a patriarchal society, in which men hold the power and women have little formal power, even if they may have some personal persuasive power. Although when compared to the restrictions we’ve explored on women of the late 19th and early 20th century many of our societies may no longer appear to be patriarchal, others would still argue that the main tenet of patriarchy – where predominately men hold power – remains in most if not all societies. We might also reflect on the extent to which the idea of ‘the man as guardian’ remains in today’s society, even if in different and less formal forms. Later in this course we will explore media representations of gender inequality, where we’ll see how some of these tropes (the strong protective man as the norm, the strong independent woman as the exception) still influence our thinking.

Parental rights

The rights of parents present to us an interesting picture. As we have seen, for some time children were considered to be the possession of the father but generally the responsibility for the upbringing lay with the mother. In England in 1836 Caroline Norton, a prominent literary figure, was denied access to her children upon separating from her husband, it is claimed so the husband could maximise injury to her [1]. That coupled with the withholding of financial assistance, both of which were then legal, led to an extensive period of campaigning to change the law, which Caroline executed through her political contacts and writing. Her efforts are argued to be instrumental to the change in law in England and Wales in 1839 leading to the custody of children being given to the mother for children under the age of seven (as long as the mother had not been proven to have committed adultery), and for non-custodian parents to retain access. Her campaigning also led to changes in property and matrimonial law.

Today we see campaigning organisations, such as fathers for justice, addressing concerns about the lack of access fathers have to their children and calling for equal parenting rights. Although joint custody is typically favoured in the European Union more broadly, in the UK it tends towards awarding primary custody and responsibility for the daily upbringing to mothers, although this is based on criteria perceived to be in the best interests of the child rather than a presumption of entitlement for either parent. Given one of the criteria is related to a parent’s historical nurturing role, and the tendency for mothers to take on more of this role than fathers (although this is by no means always the case), it is unsurprising that mothers are more likely to take on primary responsibility. But this can be challenged, and fathers are often successful in such cases. Underlying these decisons is the typical work-family arrangement that sees women take on the primary responsibility for childcare, even in dual-earning households. We’ll explore this in more depth over the coming weeks.

Education

Education has also been gendered, with less educational opportunities afforded girls when compared to boys in some countries. Education is also heavily influenced by the societal context, and the wealth of the parent where education requires payment. The overall global picture demonstrates that women exceed men in completing the most tertiary (bachelor, and masters-level) education. This is reversed when looking at doctorates, and those who go on to undertake a career in research, according to UNESCO. However, this obscures ongoing inequalities, such as unequal access to primary school education for girls [2]. According to UNESCO, in Africa 9 million girls between the ages of 6 and 11 will never attend school, compared to 6 million boys.

Historically, educational needs were perceived to be different, with girls in Britain, where educated, more likely to receive a home education focused on their prospective roles as future wives and mothers, or given a range of accomplishments, such as learning music. In contrast, subjects such as mathematics and science were typically reserved for boys who were anticipated to take on a profession. Education was also related to class, with girls of the working class receiving an education (if at all) commensurate with her anticipated future, such as taking on domestic work. Girls were not encouraged academically, and it was even considered that they were not suited to certain subjects by not having the appropriate minds.

Although in most countries access to education is gender equal, and legally mandatory, some of the legacies remain, particularly in relation to subject matter, with women more likely to take on Social Sciences and Humanities subjects and being underrepresented in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. It remains unclear to what extent this is due to their preferred choice or socialisation and expectation management on the part of others that shapes their perceptions and choices. There are also still those who argue that women are not well-suited to science, as articulated in 2018 by a senior scientist. Education is also influenced by health inequalities, such as the treatment of and support for menstruation. In circumstances where there is a lack of sanitary products, girls are often effectively barred from attending school. A recent UNESCO report estimates this affects one in ten of girls in Sub Saharan Africa.

Legislation

The laws and policies of a government have also played a key role in shaping relations of gender equality over time. As we have already seen, laws on property, child custody, divorce and voting, as well as policies on education can all play a significant role in shaping this. But it’s also worth reflecting on the limitations of legislation.

For example, in the UK the 1919 Sex Disqualification (Removal Act) aimed to ensure individuals were not disqualified from taking on civil roles on grounds of their sex or marriage, but this legislation was rarely invoked in court. The reasons for this are multiple, residing in the legislation itself, and its timing during the inter-war years where attitudes towards women working were impacted by the role of men returning from war. The legislation remained on the statute books for nearly 100 years almost entirely ignored. The 1973 Sex Discrimination Act, fifty-four years later, is often treated as the first sex equality legislation as the former act is forgotten.

In many countries, particularly so-called economically developing countries, the legal rights of women still lag behind. Furthermore, legal rights are only part of the problem, as is demonstrated in the case of Kenya where religious and traditional cultural practice mean that some women are still denied equal treatment, as outlined in a recent paper by Harari. These aspects of gender inequality outline some of the ways in which women’s lives, particularly in the British context, have been shaped over time and the resulting inequalities that have resulted. It sets the scene for understanding gender inequality in contemporary society.

References

- Reynolds, K. D. “Norton [née Sheridan], Caroline Elizabeth Sarah [other married name Caroline Elizabeth Sarah Stirling Maxwell, Lady Stirling Maxwell] (1808–1877), author and law reform campaigner.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2014 . Available from http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-20339. [Accessed 28 Mar. 2019] DOI https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/20339

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. “Gender Equality and Women’s Rights in the Post-2015 Agenda: A Foundation for Sustainable Development.” Available from http://www.oecd.org/dac/POST-2015%20Gender.pdf[Accessed 28 Mar. 2019]

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free