What Is Gendered Language?

Share this step

One of the ways in which we can become aware of how our societies are inherently gendered is by examining how language is used (and is gendered) in everyday life.

This will be culturally dependent with some countries having more evidence of gendering than others – much of which we will take for granted. In some countries the language itself is gendered, with many – such as French – having masculine and feminine nouns. Whilst some words appear to be linked to gender for a discernible reason, it is often an arbitrary association.

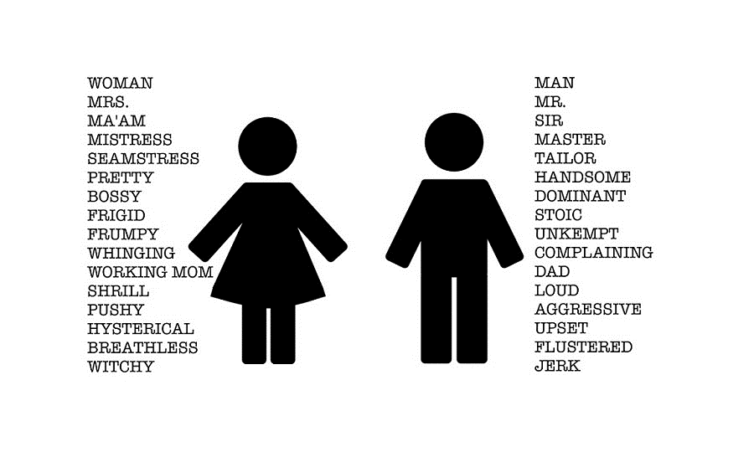

Here we are not interested in grammatical gender, but the gendering of words and phrases, many of which we might take for granted, that shape our thinking about what is masculine and feminine, male and female and thus perpetuate assumptions and stereotypes in society.

Why is this important?

Language acts as a form of symbolic code and because it does this in a subtle way it can have a significant influence on our thinking in a way that we don’t question because it feels ‘natural’. This symbolic code is also known as ‘semiotics’. In essence semiotics explores the practices by which we attach significance or meaning to things through our social practices. In other words, it considers how something becomes ‘code for’ or a ‘signifier’ for something else. Because these emerge from social practice we can appreciate that these change over time, and that they must be influenced by relations of power to direct that change (or sustain its continuation). By looking at language anew, we can identify the ways in which it shapes our thoughts and actions and also think more carefully about the underpinning social practices that sustain them.

For example, the word ‘pink’ has become associated with and seen to be symbolic of ‘feminine’. It is associated with girls rather than boys, and women rather than men, which we witness through the colour choice of clothes, toys, accessories for females, and even official signage, as the image below reflects. We have phrases such as ‘pink-collar work’, used to denote low paid, low status work typically undertaken by women, such as care work. ‘Pink’ is also associated with LGBTQ (which stands for: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer), which in turn is a community of people often assumed to be more feminine than masculine. In Italian a “romanza rosa” (a “pink romance”) is a romantic novel targeted at females.

This image is attributed to the toilet signage on an All Nippon Airways Boeing 767-300 (image courtesy of WhisperToMe, Wikimedia Commons)

This image is attributed to the toilet signage on an All Nippon Airways Boeing 767-300 (image courtesy of WhisperToMe, Wikimedia Commons)

And yet if we look at the use of pink over time we can see its role has changed as pink has been considered a colour suited to boys rather than girls, as illustrated in the picture below that shows a boy in a pink outfit with a whip in his hand. This demonstrates how the symbolism is socially constructed and can change over time.

‘Young Boy with Whip’ circa 1840, Anonymous American School Painting, Honolulu Museum of Art, Copyright: Public Domain – US.

‘Young Boy with Whip’ circa 1840, Anonymous American School Painting, Honolulu Museum of Art, Copyright: Public Domain – US.

The label ‘pink’ denotes female and feminine, but we can see this isn’t an entirely neutral association as it is also linked to characteristics perceived to be feminine – e.g. caring and emotional – and excludes others (such that are reflected in the 19th century picture, where the whip expresses discipline and control). Furthermore ‘pink’ isn’t considered to be high status.

The task

Give some examples from your own experience of how language is gendered. This might be linked to the dominance of masculine pronouns and examples of where the default assumption is that the person is a man. Or it could be the use of equivalent words attached to men and women where there are significantly different connotations. Or it can be phrases that are typically associated with a man or a woman.

Some examples, to start us off

- In the English language there has been the tendency to use ‘he’ in text to refer to both men and women, and likewise ‘man’ to refer to men and women. This is gendered approach that has begun to shift, with a much greater use of a gender neutral word, or ‘she’ instead, but the practice still exists. The reliance on the masculine form to speak for all genders can also be found in the expressions ‘man-kind’ and ‘man-made’ and these are often used to this day.

- There are occupations that we almost always describe as if only occupied by men, such as firefighting. Based on the dominance of men in this profession, there is a tendency to refer to ‘firemen’ and rarely ‘firewomen’. In some professions we have resorted to changing the expression used (for example, we tend to refer to a police officer rather than a policeman or policewoman).

- There are often more negative connotations associated with roles that are associated with men rather than women, even though they are equivalent. For example, the term used to describe a single man – a bachelor – is generally seen in more favourable light than its equivalent for a single woman – a spinster. The former conjures an image of a person who enjoys his own company and has freedom to act as he pleases, and the latter of someone who is unwanted and unable to find a partner. It is also likely to create an image of an older rather than a younger woman, whereas bachelor doesn’t have such strong associations with age. The reasons behind this lie, as our timeline shows, in the historical significance of marriage to women.

- We can also see the differential role that marriage has played in a woman’s life in expressions such as ‘catch a man’. Indeed if you search online for ‘finding a wife’ you’re as likely to be directed to sites about finding partners for physical liaisons as you are to finding a life partner. Conversely if you search for ‘finding a husband’ you’re likely to be directed to sites helping middle aged women who have so-far ‘failed’ to secure a husband. The meanings behind these equivalent marital ambitions therefore appear to have different connotations.

Consider also, the gendering of the following:

- Who is masterful? Is it usually the person who has mastered their craft, or a man?

- How often is a mistress the female equivalent of a master, or a woman who plays a companion role to a man?

- How often do you hear phrases like “Boys don’t cry” and “Boys will be boys” said in equivalent terms of girls?

- Are men called bossy? Or just “the boss”?

These examples are taken from the UK context, and although they may apply equally in other contexts, they might not always be applicable.

Spend a bit of time coming up with other examples and thinking about how and why they might be gendered, and the consequences of this gendering. Where possible indicate the country or area of origin. That might also help explain how they came to be, and why they still are in operation.

Also, think about:

- Should we move to gender neutral language, and if so, what is the advantage?

- What might be the disadvantage (if any) of moving from masculine or male -dominated language to gender neutral language (rather than introducing the feminine)?

- Why are gendered expressions problematic?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free