What is Rotoscoping?

Share this step

There’ll come a time when you just can’t key an object. Either the background is just not distinct enough from the foreground, or maybe a fussy director wants you to key something out of a shot that actually hasn’t got a plain background at all (companies like MPC get this request all the time). In cases like this you need to resort to Rotoscoping, or ‘Roto’ as it’s often called.

However, most of the times you’ll use roto as a technique is as an additional assistance to your key. Roto’ing creates a mask by drawing shapes onto a layer. If you think about first principles, what you are doing when you pull a key is making a matte. Now you may never see that matte, but it’s there. You saw it briefly in the HitFilm exercise- the black and white image that shows which areas of the driver and car were white (opaque) and which parts of the image let the background through (the window). So drawing roto shapes does the same thing, except you are drawing a matte by tracing over something in your shot.

Conceptually, think about having a pair of scissors and a book of a film of someone dancing from a musical. Let’s say they are shot against an ugly theatrical background which you wish wasn’t there. Now imagine each picture in this book is an individual frame from the original movie. With patience and all the time in the world, you could go through the book, cutting out individual frames with your scissors. Then, you could take all those cut outs of the dancer and stick them under a rostrum camera in order, and re-shoot them onto another more pleasing background image. It sounds like an ordeal, but it can be fun, and luckily it’s a bit more automated these days than we’ve made it sound, as you’ll see.

Roto History

To understand Roto, let’s go back in time. In 1917, animator Max Fleischer (The Fleischer Brothers were famous in the pre-Disney era with work like Betty Boop) developed the process as an aid to the laborious activity of drawing cartoons. Max had a rostrum camera pointing downwards that was adapted with the addition of a lamp so it could also be a projector. Then, frame by frame, a previously shot film was projected onto the table. Let’s say it’s the dancing person we’ve just been talking about. Paper is placed underneath and the dancing figure is traced, one frame at a time. Thanks to peg bars on the table, as each consecutive frame is traced onto a separate sheet, the images are all registered in the same place. This way, the natural movement of the filmed dancer can be copied, drawn, and re-filmed.

Now Max cleverly got his brother Dave to pose in a clown suit for the creation of some live action reference footage. This gave birth to the first rotoscoped cartoon character “Koko the Clown”. The cartoons were immediately popular. A reviewer for the New York Times wrote in 1919, “After a deluge of pen-and-ink ‘comedies’ in which figures move with mechanical jerks with little or no wit to guide them, it is a treat to watch the smooth action of Mr. Fleischer’s figure”

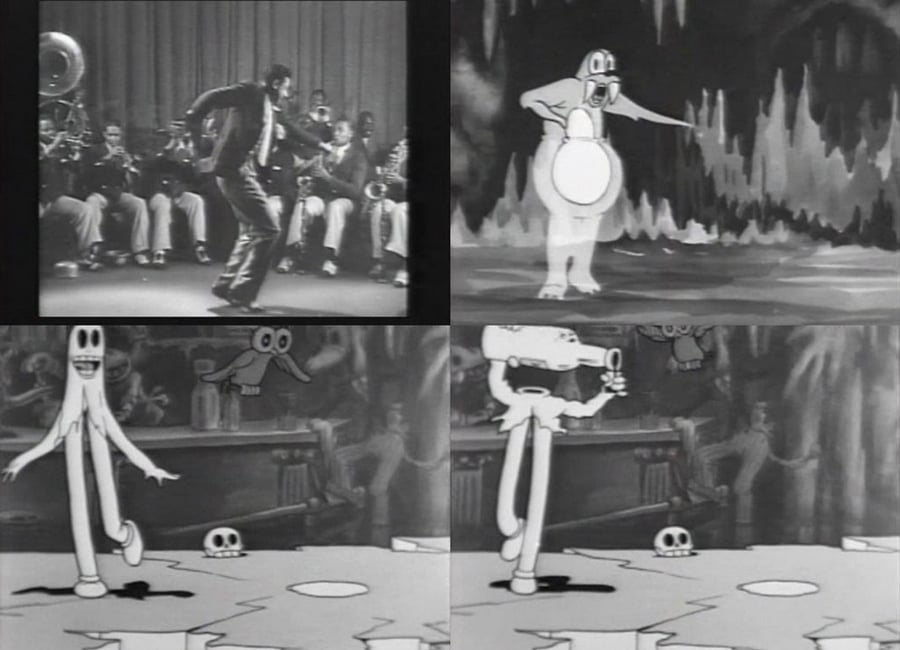

The still at the head of this article features legendary band leader and singer Cab Calloway performing “Minnie the Moocher” in 1932. You can see the animation here At the start you see footage of Calloway’s idiosyncratic act, and then at various times like 1:52 or 2:25 you’ll see a walrus creature whose movement has been rotoscoped or traced from Calloway’s performance.

This technique was eventually copied by Disney, who famously used it in the animation Snow White. Disney hired a dancer, Marjorie Belcher. Rotoscoping her movements sped up production and gave the animators a realistic reference movement. This tracing of real action soon got adopted elsewhere and took off.

Famous animator Walter Lantz explained “I would take the old Charlie Chaplin films and project them one frame at a time, make a drawing over Chaplin’s action, and flip the drawings to see how he moved. That’s how most of us learned to animate.”

VFX and Roto

Now as VFX matured and film makers started using mattes, rotoscoping became a great way to juxtapose and combine different characters and scenes. You could now draw a matte if you couldn’t key one.

In Return of the Jedi (1983) animated walking vehicles (called AT-ATs or All Terrain Armoured Transport) were matted into real forest scenes. A ‘hold out matte’ of some of the trees in the forest of Endor were hand rotoscoped frame by frame to create a matte. These were protected during optical printing, so the AT-ATs appear to walk between trees, adding a sense they were really there, in the midst of the action.

Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) needed scores of birds to attack a small town. It wasn’t possible to control the birds of course, or even key them against a background, and the nature of the shots meant the birds and a luma key against a sky wasn’t possible (some were white birds), especially as many were originally shot against cliffs, beach, or sea. So, tracing the birds was the only option. Rotoscoping the 500 frames in one shot of the attack took two artists 3 months to complete. Of course these are pre-digital film examples, but even today roto’ing big shots in feature films can take weeks.

Roto in the digital age

Most VFX based programmes have rotoscoping and masking capabilities these days. Some people prefer dedicated specialist software like Silhouette or Mocha when they have tricky work to do.

Roto in the digital age is not all about making mattes. The same tools can digitally paint and be used to remove objects from the film- like pylons, boom mics, or the public straying into shot. In the context of this week, roto is a great aid to strengthening keys. Maybe your keyed figure looks great except for one arm- in that case a well-drawn roto of that arm can be added to the matte created by the key, thus saving the key. In one of this week’s Blaine Brothers clips you’ll see Chris using masks to protect and show breath coming from a character’s mouth. That kind of subtlety at that kind of speed was undreamt of by those who had to roto film footage before the digital era. However the same skill of a good eye and attention to detail combined with tons of patience is still needed today. With VFX, if you want good results, you need to put the time in.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free