The Artistry and History of Matte Painting

Share this step

The public’s hunger for spectacle, fantasy or exotic locations has driven film since its earliest days. One of the most persuasive elements was the background, and if the background scenery didn’t exist this needed to be skilfully painted.

Even in the early days of film inventive people like Georges Méliès realised that if you stopped light from exposing parts of the film you could run it again through the camera, and how a matte box on the lens would perform this task, blocking the light to a portion of the film.

A natural extension to this was to partially paint on a large glass sheet placed up to three metres in front of the camera as it filmed a scene. Paint a picture of a castle, and then film a real mountain through the glass. Paint a lost city and film an empty desert. As long as the focal length of the camera was correct, with a large depth of field both the matte painting and the scene behind would be in focus.

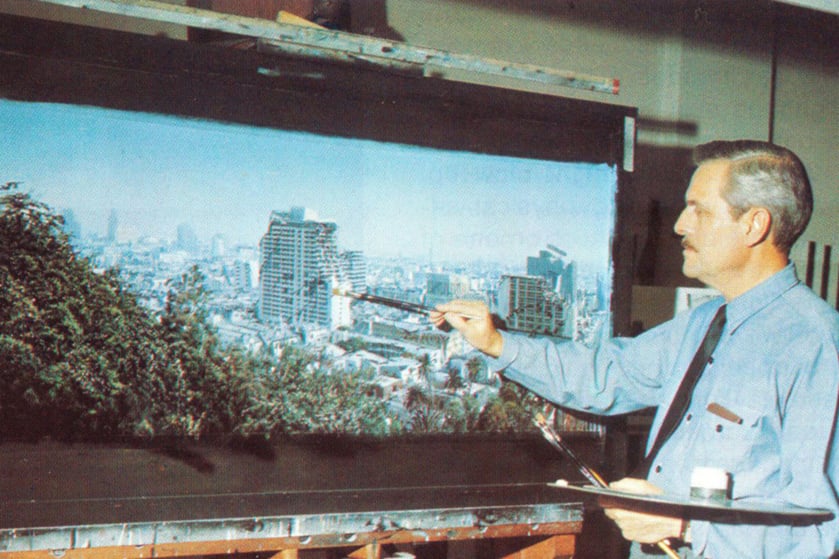

Matte Painters had to be very accomplished at fooling the eye, or what we’d now refer to as photorealism. Even if you were painting a fantastical castle the light and shadows would need to match the real surroundings, as would the colour and tonal range.

Highly-prized artists would produce such seamless work with paints or pastels that they could replace parts of a contemporary image without the audience knowing; a busy street could be made to look empty or a city deserted by judicious use of painted glass to hide unwanted portions of the camera’s view.

Norman Dawn

Norman O. Dawn (1884-1975) was credited with the innovation of using glass painting for movies, as it had been used in stills photography for many years. Amusingly, he started his career as a kind of real estate photographer, and soon learnt techniques where he could obscure unsavoury elements of a property with a little paint on glass! The first recorded example of such matte painting was in the 1907 film Missions of California. Thanks to this technique the partially destroyed and dilapidated mission buildings could be made new again, with bell towers and roofs painted in by Dawn. This was the birth of what we now call Set Extensions. Indeed, you’ll be hearing from one of Dawn’s successors, Marco Genovesi, MPC’s Head of Digital Matte Painting later this week!

It is crucial to the believability of the shot that the background and the painting shouldn’t misalign; so much was done to stabilise the camera including burying the camera’s tripod legs in holes dug in the earth to stop the heavy camera’s position shifting imperceptibly over time, especially as the painting often needed to be completed and tweaked once the camera was in place.

The other issue was the laborious task of painting the shot in the first place. Looking through the camera lens the artist would instruct an assistant to mark key lines and points with a wax pencil on the glass as a starting point, which the artist would then trace and paint over.

The next innovation

However, the problem of hurriedly creating or modifying paintings on set, with changeable weather and lighting, led to Dawn inventing the Original Negative Matte Painting method. This process started out with a large piece of glass, but instead of painting a scene, the relevant area is painted black and filmed with a ‘pin registered’ camera so there is no film ‘weaving’ or wobble as it moves through the camera.

Later in the lab a few frames of this will be developed and projected onto glass, and the surrounding film imagery and perspective will be noted, so the painting can happen without time pressure. When this is done, the area with the live action is painted black.

So now you have two films one with a matte painting and a black area where the live action was, the other containing the live action and a black area where the matte should be. These are then exposed together to make the final image. If everything is aligned and the artist is skilled enough, you’ll have a convincing final shot. You can see a great video here of Matte Painters at work.

Dawn was naturally inventive – he went on to create rear-projection techniques and filmed many miniature sequences too. Some of his notebooks and plans survive here. He became a director, famous for the effects-laden Sinbad the Sailor (1917).

Legacy

Matte artist Albert Whitlock (1915-2000), who won an Oscar for his groundbreaking (excuse the pun!) work on Earthquake (1974), took the process further by adding extra layers of matte paintings onto the final composite. Matte paintings have had a big impact on memorable scenes in cinema history. Traditional matte painting is a vein throughout cinema history; from Dorothy’s approach to the Emerald City in Wizard of Oz (1939), Scarlet O’Hara’s house in Gone With the Wind (1939), the giant warehouse in Citizen Kane (1941), to the futuristic visions of Blade Runner (1982) and Star Wars (1977) and many adventure movies like Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984).

As Craig Barron founder of the world famous but now defunct Matte World Digital company points out about matte painting:

“Many shots tend to be held on screen for longer than the average special effects shot. Matte shots are normally used for establishing shots that are quite contemplative—they tell a story or establish a scene and people look at these images for a relatively long time. That means that the quality has to be there, otherwise people will notice that something is wrong.”

It’s tempting to think matte painting is dead as it is all achieved in Photoshop these days. However, the artistic skills live on. There’s no need to paint on glass, but there is still a need to use brushes artistically in Photoshop. There is no need to match or align your painting with film frames, but there is a need to understand (at least intuitively) perspective and light. See contemporary matte artist Mathieu Raynault, whose work you may have seen as a cinema-goer to get an idea.

Matte Painting is very much alive and well in the digital age, and as you’ll see next, 3D compositing now means it’s not just the background picture glimpsed behind the actors- it’s now completely integrated into the action. In the next section we meet Marco Genovesi, MPCs Head of Matte Painting and get to see some of his spectacular work.

If you’d like to know more about this fascinating area, you might want to track down a copy of Richard Rickitt’s “Special Effects: The History and Technique” book, which is one of the best. Also “The Invisible Art: The Legends of Movie Matte Painting (2004) by Mark Cotta Vaz and Craig Barron.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free