Battle of Waterloo: Assembling an Army

Share this step

Wellington was able to report to Lord Castlereagh on 12 March the immediate plans for mustering the allied forces — once it had been ascertained that Napoleon was in fact making headway against the French king. This step looks at how those forces were assembled, shows you some of Wellington’s calculations and asks you to consider an original treaty for raising troops for the British contingent.

In mid-March, it was expected that 150,000 Austrian troops would assemble in Italy; that there would be an army on the Upper Rhine, which would build up eventually to 200,000 troops, drawing in the first instance of those of Bavaria, Baden and Württemberg, to be joined by more from Austria in due course; and that there would be a third army, on the Lower Rhine, to be comprised of a Prussian corps, the Austrian garrison at Mainz, and other troops on the Moselle. It was to this last army that the British and Hanoverian forces in the Low Countries, which Wellington was to command, were to be joined. Russian forces, some 200,000 men, were to form an army of reserve at Würzburg, and the balance of the Prussian forces was to be held in reserve on the Lower Rhine.

How was the military response to be managed?

Wellington had also met with the Emperor of Russia. The overall management of the armies the Emperor believed should be in the hands of a council, comprising himself, the King of Prussia and the Austrian field marshal, Prince Schwarzenberg. Wellington noted that the Emperor ‘expressed a wish that I should be with him, but not a very strong one; and, as I should have neither character nor occupation in such a situation, I should prefer to carry a musket.’

Resources and problems

Forces on this scale required a major commitment of resources. There were three immediate and linked problems: manpower, finance and inter-allied relations.

Manpower

The four allies had agreed on 29 June 1814 that each would keep their armies at 75,000 men. The Russian forces were mainly in Poland: although the Russian Emperor offered 200,000 men, with a further 200,000 to follow and 150,000 for an army of reserve, his forces were too far away to be of immediate use. Besides this, the prospect of a Russian army on this scale in Central Europe was far from attractive to the British. The separate article of the Treaty of Vienna recognised the difficulty Great Britain would have in meeting her treaty obligations. It seemed likely that Britain would be about 100,000 men short and that she would have to find the balance using subsidies to pay for contingents to be fielded by other powers. Too large a proportion of Britain’s army was dispersed round the world for her to respond quickly: many of the regiments that had served under Wellington in the Peninsular War were in North America, where they had been engaged against the United States. It was therefore agreed in the Treaty of Vienna that Britain might pay subsidies to other parties in order to complete her contingent.

Finance and inter-allied relations

The Emperor of Russia had lost no time in speaking to Wellington about finance. On 12 March he had intimated to the Duke that if his troops were to be engaged, he would be able to do nothing without financial assistance from England. Wellington had promised to write to Castlereagh on this score, and had suggested that in the first instance recourse might be had to arrangements under the Treaty of Chaumont, but beyond that it might be a question of a grant of a subsidy. Within a few days it was clear, too, that the other powers wanted subsidies as well — beyond the provisions of the Treaty of Chaumont, which Wellington believed was unlikely — with arms and ammunition in addition, along with arrangements for provisions (such as corn from Malta for the Austrian army that was to assemble in Italy). Wellington was convinced that it was important from the point of view of efficiency to bring as large a force as possible into the field as quickly as possible, otherwise any war would linger on.

How does Britain assemble her share of the army?

British thoughts then turned to assembling a force in the Low Countries and to answering the treaty obligations, although these men might not necessarily serve under Wellington. The Portuguese, it was thought, might offer up to 20,000 men, of which up to 14,000 might go to the Netherlands, the rest going to the Spanish frontier — but in the end the negotiations took too long for this force to be of use. More promising, but controversial with other powers, especially the Prussians, was British use of German troops, especially those from the states of north Germany, which were apprehensive of Prussian power. This potential for inter-allied rivalry was a third area of difficulty that required careful negotiation.

Wellington arrived in Brussels on 4 April. The next day he was writing to the Prussians, suggesting that they unite their forces with his Anglo-Dutch forces in the Low Countries, to protect Brussels. On 6 April he sent the first of a series of testy letters to the British government — in this case, to Lord Bathurst, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies — to instill a sense of urgency and the scale of the problem with which the allies were confronted. Wellington’s view was that the British government did not believe that war was certain or that it appreciated a great effort would be needed if that war was to be short:

You have not called out the militia, or announced such an intention in your message to Parliament, by which measure your troops of the line in Ireland or elsewhere might become disposable; and how we are to make out 150,000 men, or even the 60,000 of the defensive part of the Treaty of Chaumont, appears not to have been considered. If you could let me have 40,000 good British infantry, besides those you insist in having in garrisons, the proportion settled by treaty that you are to furnish of cavalry, that is to say, the eighth of 150,00 men, including in both the old German legion, and 150 pieces of British field artillery fully horsed, I should be satisfied, and take my chance for the rest, and engage that we would play our part in the game. But, as it is, we are in a bad way.

There was a degree of unrealism and unfairness in this request, but it had an effect.

What other troops and artillery were available?

By 12 April, beyond troops from Hanover and the Low Countries, Wellington was certain of few German forces. There was a contingent of Saxons and 10,000 men under the Duke of Brunswick — and there had been promises of men from Hesse. On 21 April, it was clear to Wellington that the ordnance he had asked the British government for would amount to no more than 72 pieces of artillery, of which 30 were German (i.e. Hanoverian) — that is, the British government would only supply 42 pieces. However, progress was being made with subsidies to make up the British contingent, and Wellington could be sure of paying for contingents from the armies of Württemberg, Baden, Prussia and Hanover.

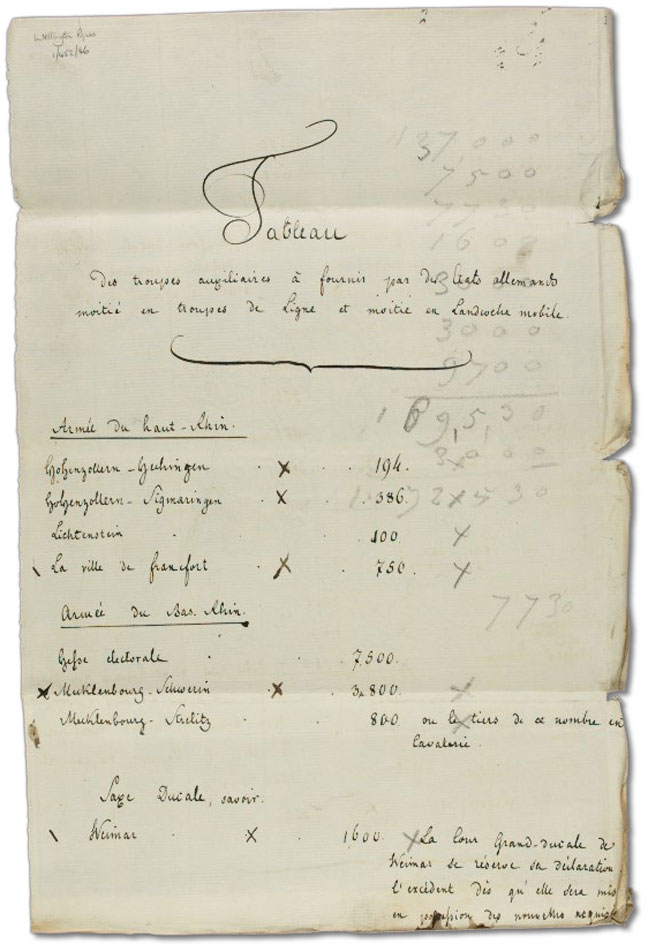

Document 1: Numbers of troops, annotated by Wellington in pencil

This lists (in French) troops from German states that were to be employed to make up the contingent promised by Great Britain under the Treaty of Vienna. Wellington’s notes show him anxious to total up the force this would enable him to put in the field.

[University of Southampton Library, MS 61, Wellington Papers 1/452/46. Crown copyright: reproduced by permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.]

Treaties of subsidy

Negotiations continued with other powers, although the troops were not necessarily destined for service in the Low Countries. Joachim Murat, the King of Naples, had taken early advantage of his brother-in-law’s escape from Elba to declare war on the Austrians — on 15 March. On 2 May Wellington concluded a treaty of subsidy with the King of Sardinia for the supply of 15,000 men: this was, coincidentally, the day on which Murat was defeated by the Austrians. Unless it could be contained rapidly, this was a war that might need to be fought across Europe. Negotiations about the supply of troops were to continue right up to Waterloo itself, and some were not destined to arrive in time.

British troops

There was progress with British troops. On 16 March, for example, while Wellington was still in Vienna, four strong regiments had been ordered to Belgium. Garrisons were taken from both Great Britain and Ireland — despite the protests of the Irish government. The Chief Secretary for Ireland, Peel, was told in mid-April that the government knew the dangers in Ireland, but ‘think it better to take the chance of danger there, for the chance of success which an addition of 5,000 men will give to Lord Wellington’. England, too, was left devoid of troops. The expectation was that the regiments from North America would fill the gaps on their return in July and August. Not all these troops had the qualities that Wellington desired — some, for example, the British veteran battalions, were destined for garrison duty. Others might be inexperienced, but nonetheless the build up was impressive, even if British troops were still joining the army in June.

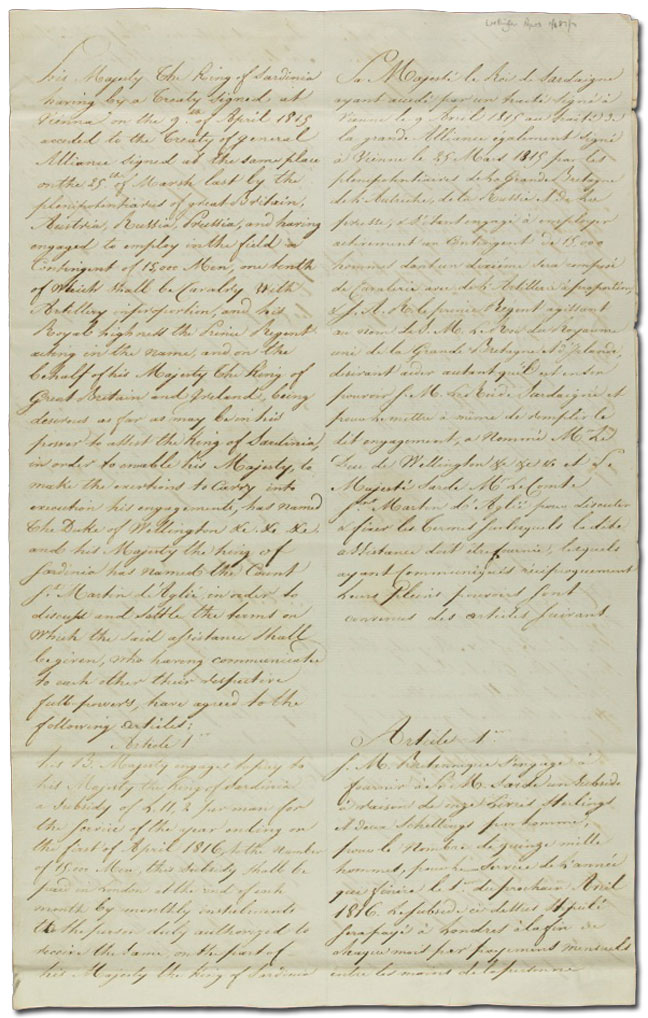

Document 2: Treaty of subsidy between the United Kingdom and the King of Sardinia, 2 May 1815

At the start of May, the Duke of Wellington concluded on behalf of the United Kingdom a formal treaty of subsidy with Sardinia which provided that the King of Sardinia would put in the field some 10 per cent of the forces that Britain was obligated to provide under the Treaty of Vienna. These forces would have been intended to serve in Italy, at least in the first instance, supporting the Austrians in their campaign against Joachim Murat, the King of Naples — although he was defeated by them on the day this treaty was signed.

[University of Southampton Library, MS 61, Wellington Papers 1/487/7. Crown copyright: reproduced by permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.]

His Majesty the King of Sardinia, having, by a treaty signed at Vienna on the 9th April, acceded to the treaty of General Alliance, signed in the same place on the 25th March last by the Plenipotentiaries of Great Britain, Austria, Russia, and Prussia, and having engaged to employ in the field a contingent of 15,000 men, one tenth of which shall be cavalry with artillery in proportion; and His Royal Highness the Prince Regent, acting on behalf of the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, being desirous, as far as may be in his power, to assist His Sardinian Majesty, in order to enable His Majesty to make the exertions to carry into execution his engagements, has named the Duke of Wellington, and His Sardinian Majesty has named the Comte St Martin d’Aglié, who, having communicated to each other their respective full powers, have agreed to the following articles.

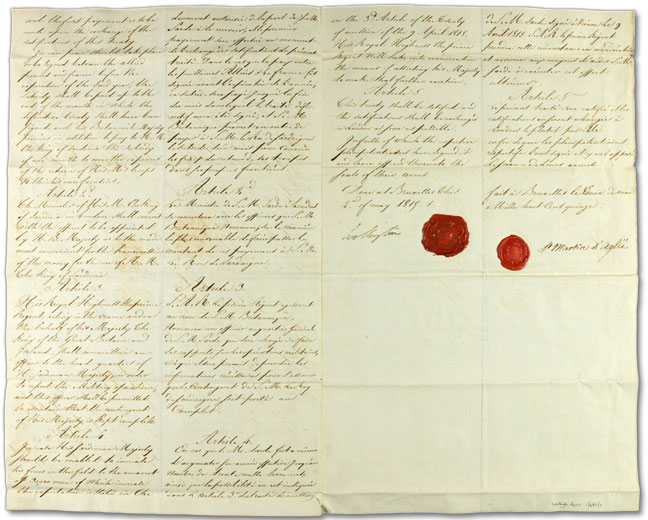

Article 1

The British Government engages to pay to the Government of His Majesty the King of Sardinia at the rate of £11 2s. per annum for each man, to the amount of 15,000 men, whom His said Majesty has engaged to maintain in active hostility against the common enemy.

Article 2

The payment shall commence from the 1st April, and shall be made in London, in equal monthly instalments, on the last day of each month. The Minister of His Sardinian Majesty shall concert with the officers of the British Commissariat as to the mode most convenient to transmit the money for His Majesty’s use.

Article 3

His Royal Highness the Prince Regent, acting in the name and on behalf of His Majesty, shall have a right to commission an officer to the headquarters of His Sardinian Majesty in order to report the military operations; and this officer shall be permitted to ascertain that the contingent of His Sardinian Majesty is kept complete.

Article 4

This treaty shall last till the end of the year 1815, unless the object of the General Alliance should have been sooner attained; in which case the payments stipulated in Articles 1 and 2 shall cease in one month after the object shall have been attained.

Signed and sealed by the Duke of Wellington and the Comte St Martin d’Aglié

[Printed in WD, xii, p. 342; with blanks filled in from the treaty itself, University of Southampton Library, MS 61 Wellington Papers 1/487/7.]

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free