Battle of Waterloo: Exile of Napoleon

Share this step

Although Napoleon attempted to rally his troops and wanted to continue to fight, it was apparent particularly to the politicians in Paris that he had no future, and that the allies would not cease their campaign until he personally surrendered.

On 22 June he named his son as his successor — but this was something that neither the French Assemblies nor the allies would ever be likely to countenance. The question was what would he do, especially given that the allies had engaged by treaty against him personally, and not against France and the French people — and many were beginning to see the advantages of disabusing themselves of Napoleon. One plan was that he might go to the United States, like other exiles from revolutionary and imperial France — and the French government started to put this in train. The prefect at Rochefort was instructed to expect him and two frigates were assigned to accompany him. But the Royal Navy was blockading the French coast and it was not likely that Napoleon would make an escape that way. It seems probable that Napoleon thought he would be safer in British hands than those of his fellow Frenchmen, and therefore determined to surrender to the British rather than attempt to run the blockade.

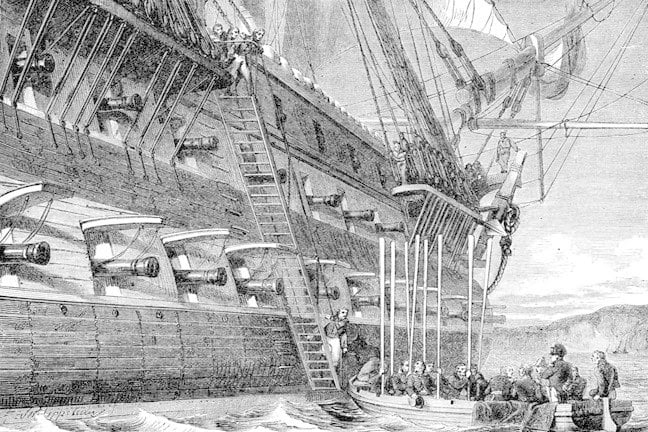

On 13 July, Napoleon wrote a brief letter to the Prince Regent, putting himself on his mercy. Arrangements were made the following day with Captain Maitland of HMS Bellerophon for Napoleon to surrender to him and to board the vessel — an eventuality against which Maitland already had instructions from the Admiralty [see Document 1] — and Napoleon duly did so on 15 July, placing himself on the mercy of the Prince Regent.

What will the allies do with Napoleon?

Although in March 1815 the allies had declared Napoleon an outlaw, they did not in June that year have a settled opinion on how to deal with him as an individual. That discussion was closely linked to political questions about the government of France and how the allies might join together in a solution to this end. The British government gave this serious consideration in late June and early July — and a plan gradually emerged that obtained the support of the allies.

The Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, writing privately to the Foreign Secretary, Lord Castlereagh, on 30 June 1815 [see Document 2 (PDF)], set out his view of forthcoming negotiations. Castlereagh was to lead the discussions with the allies for Great Britain. Lord Liverpool considered three scenarios: the restoration of Louis XVIII, with Napoleon dead or a prisoner in allied hands; the restoration of Louis XVIII, but with Bonaparte alive and in the United States or elsewhere; and, thirdly, that it would have become impossible to restore Louis XVIII, however desirable that might have been, and that it would therefore be necessary to treat with some other government representing France — the government had prepared itself for this eventuality in the way that it had ratified the Treaty of Vienna in April. Liverpool was conscious that the British government did not know the opinions of its allies. At the same time, he was keen for there to be some form of exemplary justice for those supporters of Napoleon who had previously sworn loyalty to Louis XVIII: this was treason.

Castlereagh was to be in Paris in early July, in the expectation that the other European leaders and sovereigns would go there as soon as they learned that the city had surrendered. Liverpool wrote further to Castlereagh on 7 July, setting out the three questions that were on everyone’s mind. What is to become of Bonaparte? What should be done about those who assisted him in regaining power? And what should be done with the French armies? He then rehearsed at length the question of what to do with Bonaparte and why this one man deserved such attention [see Document 3].

Exile on St Helena

The decision about what to do with Napoleon was to be an easier one than settling the government of France. While there were arguments in favour of Napoleon’s execution, that was not the course that prevailed. Castlereagh was able to write to Liverpool on 24 July that the allies had no difficulty in leaving the custody of his person with the British government, perhaps subject to some agreement not to release him without their consent. The British government had decided that he was to be placed in exile at a location where it was beyond his capacity to disturb the peace of Europe. Maitland’s letter announcing Napoleon’s surrender to him reached London on 24 July and Lord Bathurst, the Secretary of State, immediately wrote to Wellington:

We have nearly determined, subject to what we may hear from Paris in answer to Lord Liverpool’s letter a week ago, to send Bonaparte to St Helena. In point of climate it is unobjectionable, and its situation will enable us to keep him from all intercourse with the world, without requiring all that severity of restraint which it would be otherwise necessary to inflict upon him. There is much reason to hope that in a place from whence we propose excluding all neutrals, and with which there can be so little communication, Bonaparte’s existence will be soon forgotten.

If the hope of oblivion for Napoleon was misplaced, the solution did in general meet the allies’ requirements for the duration of Napoleon’s life — although there was long-running conflict between the former emperor and Hudson Lowe, the governor of the island. A British regiment was also stationed on St Helena — it was noted, however, that no regiment should stay with Napoleon for too long a period.

Document 1: The surrender of Napoleon: letter from Captain Frederick L. Maitland to John Wilson Croker, the Secretary of the Admiralty, HMS Bellerophon, Basque Roads, 14 July 1815

For the information of my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty I have to acquaint you that the Count Las Casses and General Allemand this day came on board HM Ship under my command with a proposal for me to receive on board Napoleon Bonaparte for the purpose of throwing himself on the generosity of His Royal Highness the Prince Regent.

Conceiving myself authorized by Their Lordships’ secret order, I have acceded to the proposal, and he is to embark on board this ship tomorrow morning. That no misunderstanding might arise, I have explicitly and clearly explained to the Count Las Casses that I have no authority whatever for granting terms of any sort, but that all I can do is to convey him and his suite to England, to be received in such a manner as His Royal Highness may deem expedient.

At the request of Napoleon Bonaparte, and that Their Lordships may be in possession of the transaction at as early a period as possible, I despatch the Slaney with General Gourgaud, his aide de camp, directing her to put into the nearest port, and forward this despatch by the First Lieutenant; and shall in compliance with Their Lordships’ orders proceed to Torbay there to await such direction as the Admiralty may think proper to give me.

Enclosed I transmit a copy of the letter with which General Gourgaud is charged from Napoleon Buonaparte to His Royal Highness the Prince Regent; and request you will acquaint their Lordships that the General informs me he is entrusted with further particulars which he is anxious to communicate to His Royal Highness.

Enclosure: Napoleon to the Prince Regent, 13 July 1815 [translation] Exposed to the factions that divide my country and to the enmity of the greatest powers of Europe, I have ended my political career and I come like Themistocles to seat myself at the hearth of the British people. I place myself under the protection of the laws, which I seek from Your Royal Highness as the most powerful as well as the most constant and most generous of my enemies.

[SD, xi, pp. 30–1, collated with University of Southampton Library, MS 61, Wellington Papers 1/473/95. Crown copyright: reproduced by courtesy of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.]

Document 3: Extract from a letter from Lord Liverpool to Lord Castlereagh, 7 July 1815, on the future of Napoleon

I conclude the Emperors and King will come to Paris as soon as they hear of the capitulation. By that time we shall be able to form some judgement of the probable fate of Buonaparte. If he sails from either Rochefort or Cherbourg, we have a good chance of laying hold of him. If we take him, we shall keep him on board ship till the opinion of the Allies has been taken. The most easy course would be to deliver him up to the King of France, who might try him as a rebel; but then we must be quite certain that he would be tried in such a manner as to have no chance of escape. Indeed, nothing could really be necessary but the identification of his person. I have had some conversation with the civilians [civil lawyers], and they are of opinion that this would be in all respects the least objectionable course. We should have a right to consider him as a French prisoner, and, as such, to give him up to the French government. They think likewise that the King of France would have a clear right to consider him as a rebel, and to deal with him accordingly.

If it is asked why so much importance is attached to one man, it is because I am thoroughly convinced that no other man can play the same part as he has done, and is likely to play again if he should be allowed the opportunity. Independent of his personal qualities, he has the advantage of fourteen years’ enjoyment of supreme power. This has given him a title which belongs to no other man, and which it would be very difficult for anyone to acquire.

[SD, x, pp. 677–8.]

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free