The Waterloo Museum

Share this step

Waterloo was to exert a powerful influence on the public imagination. Commemorations and celebrations of the battle manifested themselves in different ways.

In Great Britain, at one end of the scale were the day of national thanksgiving for the victory (7 July 1815) and philanthropic work for the wounded and the families of those killed at the battle; at the other were enthusiastic literary outpourings and the souvenir trade. Exhibitions of artefacts connected with the battle, commemorative paintings, military equipment and items which evoked imperial France, the enemy and Bonaparte himself were to prove popular with the general public. Napoleon Bonaparte had long been both a figure of hate and fascination for the British. A cartoon by Cruikshank showed ‘A swarm of English bees’ — the bee had been an emblem both of Napoleon and the ancient kings of France — some of the estimated 10,000 daily visitors to a display of Napoleon’s battlefield carriage.

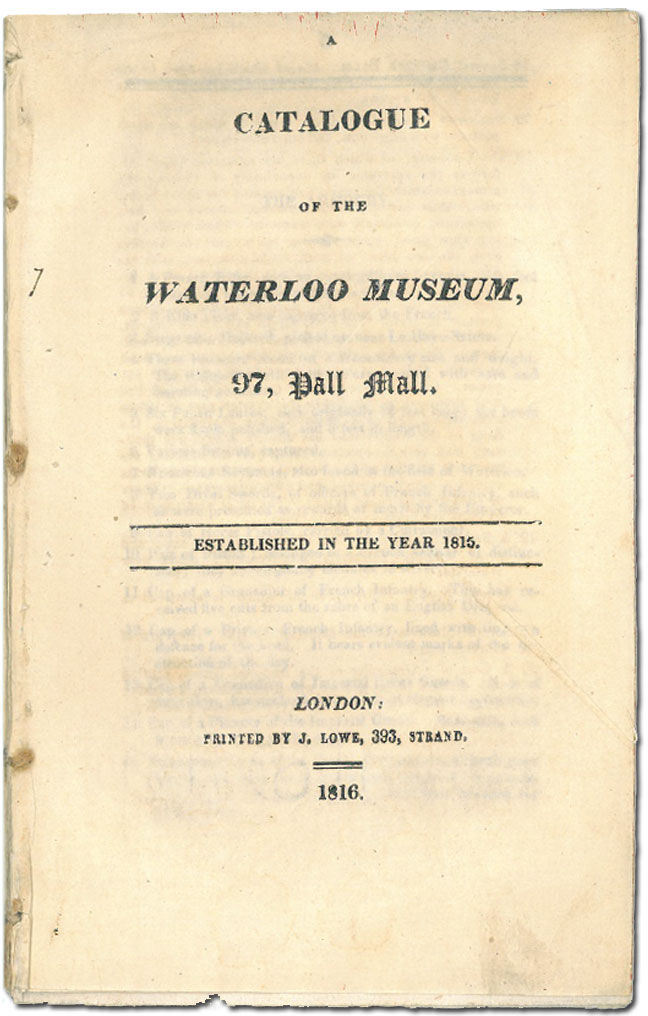

Opened in November 1815, the Waterloo Museum was located at 97 Pall Mall. It was one of a number of London establishments that targeted the insatiable public interest in the battle. Retired soldiers and men who had lost limbs in the battle were employed to staff the Waterloo Museum. Not only did this create a direct link with the battle and a sense of authenticity — the public would have enjoyed the exploits the staff could recount — it also drew on the feeling of benevolence towards those who were wounded in the action. The euphoria around the victory at Waterloo changed the general public view of the military: in normal circumstances, the common soldiers of the army had not been well regarded.

The armoury

The catalogue of the museum, published in 1816, gives an insight into what had made it popular. The first room was an armoury, with weapons and other military items collected from the battlefield. Everything about it was remarkable. The very first item was a French rifle ‘with an extraordinary bayonet, two feet in length’; a French grenadier’s cap (catalogue number 11) had five cuts, received from the sabre of an English dragoon; there was a group of sabres of French cuirassiers, ‘of prodigious length’ (15); and a further section in this room included the armour that Napoleon had used for his heavy cavalry (18).

Their bodies being thus proof against either sabre cuts or musket shot, the men advanced with confidence, and, with sabres of unusual length, imagined themselves to be invincible. … The Scots Greys and Horse Guards, with the Blues, and Inniskillens, alone could cope with them. By seeking their vulnerable parts, the neck or arms, they soon became equal, and at length superior.

Embedded in this collection, therefore, was evidence of the courage that had enabled the allies to win the battle.

Napoleonic memorabilia

The Grand Saloon contained clothing and relics of Napoleon, his family and the marshals of his armies. These were symbols of the imperial power that had been displaced with his defeat at Waterloo: they were not just spoils of war, but clear evidence of the downfall of the man the British had long considered a ‘tyrant’. Here were to be found a hat and coat worn by Napoleon on Elba (51–2), the foot board and panel of his state carriage (68, 76); Napoleon’s state sword, saddle, breastplate and harness (83), as well as the suit worn by Napoleon’s son, the King of Rome (as a three-year-old) at the review of the Imperial Guard on its return from Moscow (59), robes of Prince Jerome (84) and Joseph Bonaparte (85), and Joachim Murat’s military pelisse (56). Poignantly, the exhibition in the Grand Saloon also included clothing of Louis XVI (77–80), and of the revolutionary leader, ‘the execrated Robespierre’ (82). A further relic of Robespierre was in a case — his sword, ‘very superb, with Republican mottos and ornaments’, with legends on the blade ‘Pour ramener la paix’ (‘To bring back peace’), ‘Pour le salut de la Patrie’ (‘for the safety of the country’) (96). There was also a fine library clock from the palace of St Cloud, adorned with figures of Napoleon and a female petitioner, interceding for her husband arrested as a conspirator in a plot to assassinate the Emperor after the fall of Berlin (93) — Napoleon allowed her to destroy the evidence against him.

The paintings

Amongst the paintings was an impressive canvas executed at Napoleon’s request in 1811 by Robert Lefèvre (1755–1830), a portrait of Napoleon in his coronation robes, the picture measuring 15 feet by 6 feet (75). In contrast to this imperial triumph was a painting of the entrance of the allies into Paris, in March 1814, showing the Emperor of Russia and King of Prussia and their military staff (74) and much more modest painting, of the Battle of Waterloo by the Flemish artist Constantine Coene (1780–1841) (71).

The 24-page catalogue of the exhibition devoted almost two entire pages to describing Coene’s canvas, praising it for its authenticity, and drawing out the human drama and the realistic representation of war. Depicting the battlefield late in the afternoon, when the French were preparing to flee, Coene shows Wellington, attended by his aide de camp, Major Fremantle, and his staff officers to the right of the painting pointing to a distant spot where the smoke of the Prussian cannon is rising on the horizon. Wellington is dressed in a plain manner, unlike the pomp and imperial glory of Napoleon’s coronation robes. At the rear of the army are wounded soldiers and the widow of an artillery man laments over her husband. In the centre is the main action between the Scots Greys, Inniskillens and the French Cuirassiers. The Scots are shown attacking the cuirassiers. who fall from their horses or flee the field. The farm in front of this is La Haie Sainte, with Hougoumont in flames to the right. The catalogue notes that Coene went to the battlefield immediately the French retreated, where ‘receiving every assistance from the staff officers whose wounds permitted them so to do, he designed this painting, which, for correctness of circumstance relative to the battle is allowed to be, by general admission, incontrovertibly accurate, and, in miniature, the contest itself’.

Note: we cannot find any images or modern record of this painting – so if you can provide any information about this, please let us know through the comments.

The Waterloo Museum experience

The Waterloo Museum allowed the public to get as close to the authentic experience of battle as they could be, without going to Waterloo itself. Here they could reflect on the fate of Louis XVI and the French Revolution, see the imperial glory of Napoleon, and follow the Battle of Waterloo itself in an assemblage of prodigious objects, talking to those that had taken part, while admiring the most realistic of images of field.

Activity

You might like to experience visiting the Waterloo Museum. The catalogue can be downloaded from the link below. What are your favourite items, and why?

[© University of Southampton Library, Rare Books DC 241: 00044728]

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free