The Duke of Wellington’s State Funeral in 1852

The Duke of Wellington died on 14 September 1852, aged 83, at Walmer Castle in Kent. ‘On this day Arthur, Duke of Wellington, perhaps the greatest man that ever drew breath, departed’, noted Lady Shelley in her diary entry. His death led to an outpouring of national grief.

In the aftermath, there were discussions about his greatness, his personification of a national character and heroic identity. For a period he was again elevated to the status he had enjoyed in 1815. The Times wrote in his obituary that ‘He was the very type and model of the Englishman’, whilst Queen Victoria declared him ‘the GREATEST man this country ever produced’.

A state funeral

The Crown decreed that the Duke should have a state funeral. Prince Albert, with Lord Derby, the Prime Minister, and Spencer Walpole, the Home Secretary, oversaw the arrangements. State funerals were exceptional occasions: the last ones had been those of Nelson in January 1806 and of the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, the following month. Wellington’s funeral was to be on an unprecedented scale.

Preparations and the lying-in state

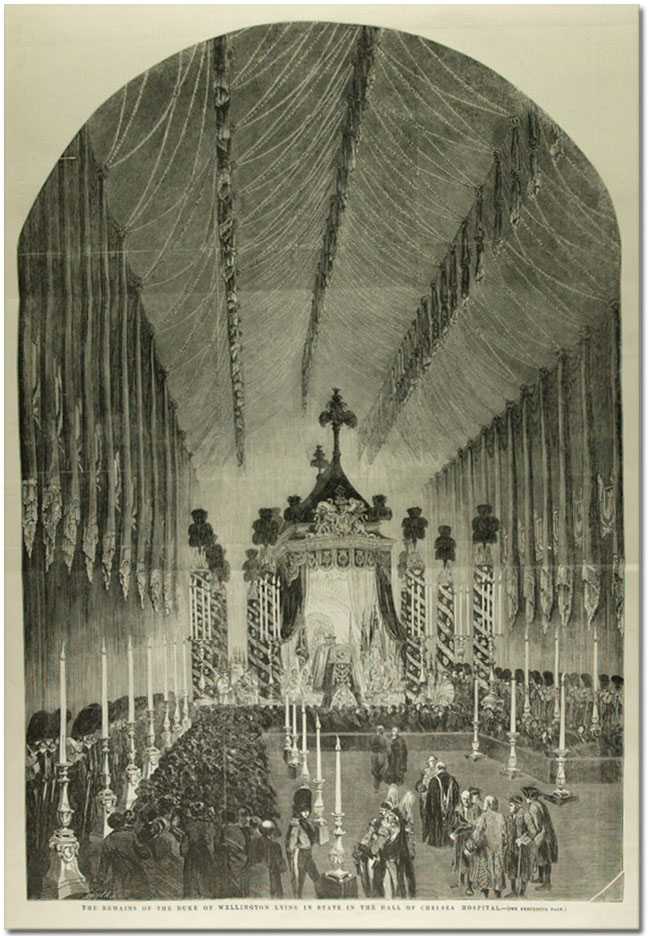

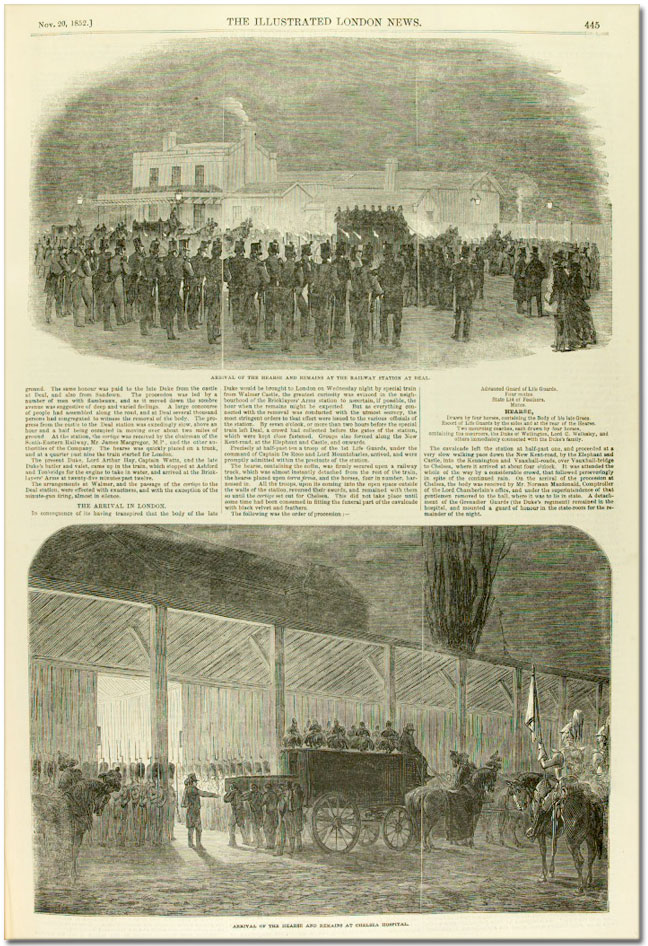

18 November 1852 was set as the date for the funeral. Wellington’s body remained in Walmer for eight weeks while preparations were made and to allow time for Parliament to reconvene to give formal approval for the expense of the funeral. The Duke’s family opened Walmer to the public on 9 and 10 November and thousands visited to pay their respects. The body was then transferred to London by train for a lavish lying-in state at the Royal Military Hospital, Chelsea, for four days from 13 November. An estimated 250,000 people filed passed the body while it was there.

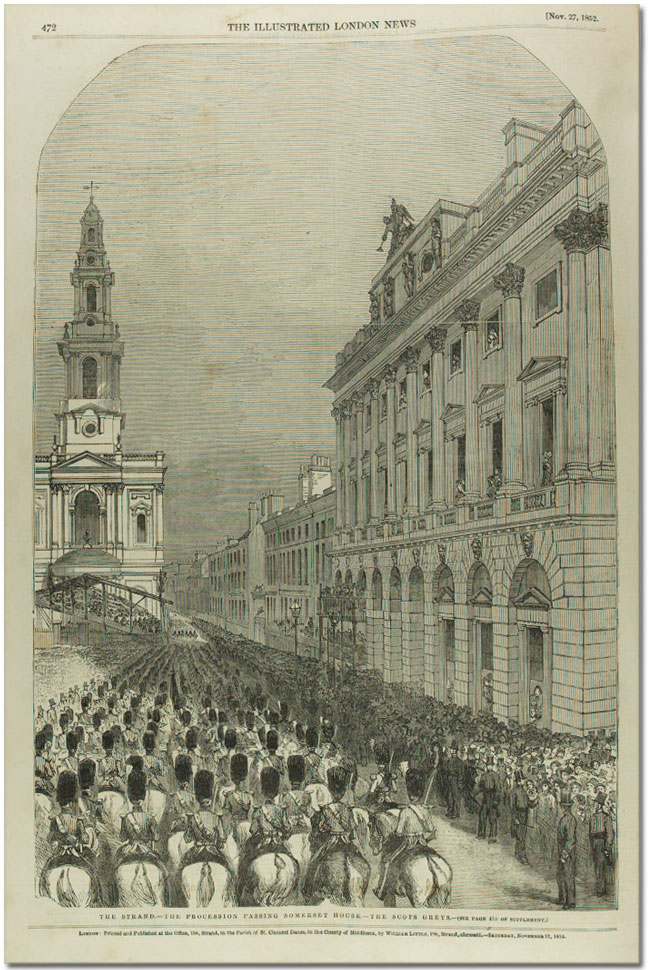

On 17 November, the body was transferred to the Horse Guards — the headquarters of the army, of which the Duke had been the commander in chief — from where the 10,000 strong funeral procession, with Prince Albert at its head, set out early the following morning. Wellington’s coffin was placed on a huge funeral carriage made of bronze, which required twelve horses to draw it. Immediate family and close friends walked behind. The procession moved slowly and it was mid-afternoon before the service was concluded and the coffin lowered into the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral next to Lord Nelson to the Dead March from Handel’s Saul. The Duke’s sarcophagus was of a coarse-grained granite.

A monument to Wellington, the work of Alfred Stevens (incomplete at his death in 1875), was erected in the cathedral in the chapel of St Michael and St George, although it has since been moved to the north aisle of St Paul’s. Now surmounted by an equestrian statue and rich in the symbolism of military victory, it includes two groups of figures on the plinth, of Valour crushing Cowardice, and of Truth thrusting Falsehood aside.

Popular enthusiasm

The interest in the funeral was a great as the lying-in-state. There was hardly enough room for those attending the funeral in St Paul’s. The whole of the route of the funeral procession was thronged with people: according to The Times more than 200,000 seats had been made and offered for sale. Shops along the Strand rented out their frontage, roofs or upper stories. For those who were not able to be present in London in person, memorial services were held in churches around Great Britain. At 3 p.m. bells began tolling in every parish church across the country.

A Great Briton

The outpouring of grief, the discussions of Wellington’s greatness and the symbolism of the national hero, which accompanied the Duke’s death and funeral, marked a mythologising and commodification of the Duke. The man whom Queen Victoria described as ‘our immortal hero’ became an idealised figure, the epitome of British greatness, a hero equal to Nelson. The Ode on the death of the Duke of Wellington by the Poet Laureate, Tennyson, which appeared two days before the funeral, commemorated Wellington as the ‘greatest Englishman’, ‘as great on land’ as Nelson was a commander at sea and the ‘foremost captain of his time’. The first edition of 10,000 copies was priced at 1 shilling: it sold out very quickly.

Other commemorative works in this period were to cast Wellington in similar heroic terms — for Thomas Carlyle he was a ‘Godlike man’. Indeed, the Duke’s funeral was to mark his apotheosis. The description of the funeral in the Illustrated London News is typical of the tenor of the obituaries and reports that were to appear in the press. Such was the interest in Wellington that this weekly paper devoted more than 100 pages of print and engravings to him in the period between his death in September and the funeral in November. The funeral issues of 20 and 27 November 1852 sold 2 million copies.

This was just one example of the commodification of the figure of Wellington. There was a burgeoning market for Wellington memorabilia following his death as the public wished to commemorate the passing of this British hero by owning something associated with him. Everything from Wellington funeral cakes and wine to locks of hair and letters were advertised for sale. The Duke was an idealised national hero. Parallels could be drawn with 1810–15, a period when images of the Duke appeared on all sorts of merchandise, from clocks to snuff boxes, and there was great interest in acquiring artefacts and relics from the battlefield of Waterloo. These images have helped to shape national identity and notions of heroism: Wellington was a Great Briton.

Document: From the report of the funeral in the Illustrated London News for 20 November 1852

The grave has closed over the mortal remains of the greatest hero of our age, and one of the purest-minded men recorded in history. Wellington and Nelson sleep side by side under the dome of St Paul’s, and the national mausoleum our of isles has received the most illustrious of its dead. With pomp and circumstance, a fervour of popular respect, a solemnity and a grandeur never before seen in our time, and in all probability, not to be surpassed in the obsequies of any other hero heretofore to be born, to become the benefactor of this country, the sacred relics of Arthur, Duke of Wellington, have been deposited in the place long since set apart by the unanimous design of his countrymen . . . all the sanctity and awe inspired by the grandest of religious services performed in the grandest Protestant temple in the world, were combined to render the scene, inside and outside of St Paul’s Cathedral on Thursday last, the most memorable in our annals . . . .

Amid the rise, and perhaps the fall, of empires, amid ‘fear of change perplexing the nations’, amid earthquake and flood, a trembling earth and a weeping sky, Wellington was conveyed from his lonely chamber at Walmer to the more splendid halting-place of Chelsea, and from thence to his grave, in the heart of London. To the popular apprehension — felt, if not expressed — it seemed as if the great funeral of that great man were only to fitly be celebrated amid mystic voices predicting —

A time of conflict fierce and trouble strange,

When old and new, over a dark abyss,

Fight the great battle of relentless change;

And when the very elements seemed to sympathise with the feelings of living men at the loss of one so mighty as he had been in his day and generation.

But the hero is entombed, and the voice of his contemporaries has spoken his apotheosis. Every incident in his long and honourable life has been sought for and recorded.

Wellington’s lying-in-state, the Royal Military Hospital, Chelsea

Wellington’s lying-in-state, the Royal Military Hospital, Chelsea

Wellington’s coffin arriving at Horse Guards

Wellington’s coffin arriving at Horse Guards

The funeral procession and the Scots Greys passing Somerset House

The funeral procession and the Scots Greys passing Somerset House

All images from the Illustrated London News: © University of Southampton Library, Rare Books, quarto Per A

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free